We acknowledge the Boon Wurrung and Woiwurrung (Wurundjeri) peoples of the Kulin Nation as traditional owners of the land on which we work and live, and pay our respect to their ancestors and Elders.

The design charrettes:

Introduction by Brook Andrew

Ngajuu ngaay nginduugirr, orana.

I am a Wiradjuri Celtic man from Australia. Wiradjuri Nation is in the state of New South Wales and, along with other south-east nations, bore the brunt of British colonial invasion, which was and still is met with fierce resistance from many of our people, past and present.

In 2010, I made the artwork Jumping Castle War Memorial for the Biennale of Sydney. I had been thinking about the lack of memorials and spaces in Australia to remember the events of the Frontier Wars, reflecting not only on the Australian experience but also internationally, on all those who are still fighting for visibility in a colonial-dominated public space.1 It is an inflatable jumping castle, adorned in a black-and-white pattern of Wiradjuri design. In the corner towers hang skulls, a reference to the trade in Aboriginal human remains that closely followed the events of the Frontier Wars. Jumping Castle War Memorial met with a range of responses from viewers. One visitor kicked off her shoes, eager to jump, while another told her, “This work is about genocide, how can you jump on that?”

The Jumping Castle War Memorial instigated the current research project I have been leading since the beginning of 2016 with Marcia Langton and Jessica Neath – Representation, Remembrance and the Memorial. Based at Monash University’s Faculty of Art, Design and Architecture, this Australian Research Council-funded project concerns the Frontier Wars and possibilities for memorialization, in an international comparative study. In Australia, there is mostly official silence in the public sphere, though many artists, scholars, Elders, writers and other leaders have repeatedly called for visibility of these histories. The Aboriginal Memorial (1988), curated by Djon Mundine and made by forty-three Ramingining artists from Arnhem Land, is now permanently housed in the National Gallery of Australia, and significant artworks have been made by many First Nations artists, including r e a, Judy Watson, Fiona Foley, Julie Gough, Maree Clarke, Mumu Mike Williams and Mr Timms. A growing number of community-led massacre memorials are also being established across the country. Architecturally, much more needs to be done, and recognized, to address the brutal truths of Australia’s past and account for the 60,000-plus-year history of Aboriginal culture and occupation. More recently, Yagan Square was completed in Perth, which brings significant visibility to the Noongar warrior and, as Stephen Gilchrist has noted, to Noongar “ways of being.”2

In June 2018, we hosted a small but ambitious forum in Melbourne, the RR.Memorial Forum, bringing together an interdisciplinary cohort of twenty-seven artists, architects, Elders, scholars and other practitioners from across Australia and the world, including from Brazil, Scotland, Cambodia, Mauritius, Uganda, the United States, the United Kingdom and Aotearoa New Zealand. There needs to be greater collaboration between community leaders, artists, design practitioners and scholars for memorial projects to succeed and become places of hope and healing. Healing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is extremely important. Apart from our smoking ceremonies and community and political gatherings, there are very few public memorial places to vent our frustrations or commemorate histories that are affecting us today through intergenerational trauma.

With reference to the Australian Indigenous Design Charter, one of the aims of the forum was to brainstorm the possibilities for future memorial projects in Australia that are Indigenous-led, community-specific and self-determined. We dedicated one of the forum days to this objective and opened it up to a group of forty-five architects, landscape architects and other creative practitioners, who worked alongside our forum delegates on a program of design charrettes, hosted by the RMIT School of Architecture and Urban Design.

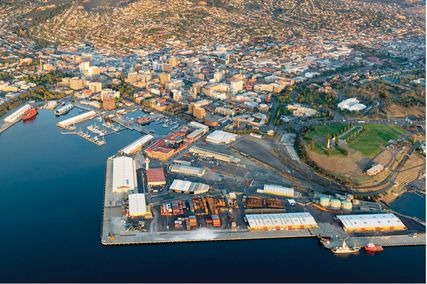

We focused on three case studies: the National Resting Place proposed for Canberra by the Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation, the Truth and Reconciliation Art Park proposed for Hobart as part of the Macquarie Point Development and the Blacktown Native Institution project in western Sydney. Addressing significant aspects of Australian history – frontier violence, the removal of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families and the continual mishandling of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander human remains – there is scope for each to become internationally renowned places of memory similar to Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, designed by Peter Eisenman.

In the charrettes, two working groups were assigned to each site. Corina Marino from the Darug Nation led the workshops about the Blacktown Native Institution project, which we describe further in this article as it proved a key discussion point for landscape architecture. Lyndon Ormond-Parker, an Indigenous heritage expert at the University of Melbourne, spoke about the National Resting Place, an area he has worked in for over twenty years. Greg Lehman, a descendant of the Trawulwuy people of north-east Tasmania, guided discussions on the Hobart project along with Ruth Langford and Julie Gough, with representatives present from the Macquarie Point Development Corporation and the Museum of Old and New Art (MONA). The charrettes were facilitated by Carroll Go-Sam, Indigenous architect and scholar from the University of Queensland’s School of Architecture, and Jock Gilbert and Christine Phillips from RMIT’s School of Architecture and Urban Design.

A number of organizations provided the support to bring this group of forum delegates together: Monash University, RMIT University, the University of Melbourne, the Macquarie Point Development Corporation, MONA, the City of Melbourne, the National Gallery of Victoria, the Koorie Heritage Trust, Negative Press and Blacktown Arts Centre. I am thankful to all the many people who came on board to support this forum.

r e a, details of Native (2013), LED sign, Sites of Experimentation, commissioned by Blacktown Arts on behalf of Blacktown City Council, 2013.

Image: courtesy and copyright the artist

Reflections by Jock Gilbert and Christine Phillips about the discipline

With a shared passion for working toward a reconciled future through Australian design practice, together we lead the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Engagement Steering Group at RMIT’s School of Architecture and Urban Design, facilitating engagement with Indigenous communities, traditional owners and knowledge holders through practice-based design research.

It was a great privilege to be invited by Brook Andrew to facilitate the charrettes for the RR.Memorial Forum and to further test a set of protocols around engagement through the three highly significant case studies outlined above. The need for memorials dedicated to the Frontier Wars in Australia can no longer be ignored, especially by Australian design professionals. Working with Brook, Jessica and Carroll, our role was to develop and facilitate an Indigenous-led, but obviously intercultural, one-day design workshop structured as a series of charrettes – helpfully framed and generously supported by our dean, Martyn Hook.

It was a deeply moving event. Leading Australian design practitioners, academics and students engaged in dialogue with Indigenous leaders and the forum delegates, paying careful attention to the principles of deep listening, storying and reciprocity.

Finn Pedersen of Iredale Pedersen Hook Architects reflected on this approach. “It does rely on the design practitioners being very conscious of their role in ‘active listening,’ allowing the Indigenous clients to lead. I have always found this very important and at times tricky when there are multiple clients in the room, requiring designers to frequently act as mediators.”

Adam Pustola from Lyons Architecture described the workshop as “more than just a design exercise, it was a learning experience that I’ve had like no other. While wanting to ‘chip in’ and participate, listening to the many conversations taking place throughout the day and around the table was immensely provoking and enriching.”

The charrettes engendered a great diversity of responses from the various teams. Some confidently produced initial design responses, while others did not. For some practitioners, there was discomfort in “telling the stories of Indigenous communities” – a kind of design amnesia – and for some case-study representatives, the articulation of issues was hindered by the range and ongoing contest of positions. Additionally, for some practitioners there was a reticence to ascribe full value to the conversational approach; having produced a design response, they wanted to undertake a more formal “site analysis.” In these circumstances, the charrettes became an opportunity to explore, uncover and share knowledge between the stakeholders and practitioners rather than work toward a design outcome, engaging in a process of “unlearning” and reorientation. The charrettes demonstrated that design practitioners are, on the whole, currently struggling to engage with Indigenous knowledge as well as with Indigenous communities.

For the interior designers, architects and landscape architects who took part, including Jen Lynch of TCL, the workshop was a transformational example of the coming together of minds. “It was completely inspiring to have all of those brains in the same space and to be a part of the conversation.”

We recognize the work required to develop frameworks and protocols and see the charrettes as part of that process. In doing so, our own practices are strengthened and enriched. To echo Corina Marino’s sentiment, it is our privilege to be invited to walk with you and your people, to honour your site and your mob.

Leanne Tobin, Men in Black (2013), installation view, Sites of Experimentation, commissioned by Blacktown Arts on behalf of Blacktown City Council, 2013.

Image: courtesy and copyright the artist.

Case study focus: the Blacktown Native Institution project.

Introduction by Brook Andrew and Jessica Neath

In the last decade, First Nations artists have been collaborating with traditional custodians to remember the children of the former Blacktown Native Institution in western Sydney and to celebrate ongoing Darug cultural practice and connection to Country. This project continues, in collaboration with the Blacktown Arts Centre and the Museum of Contemporary Art’s C3West program. It has had a profound impact on participating communities and artists, contributing to healing of the site and cooperation to develop an Aboriginal-led vision for the future of the site.

The Native Institution is the earliest example of the British removing Aboriginal children from their families for institutionalization. This practice continued into the 1970s, with thousands suffering abuse, as detailed in the 1997 national report Bringing Them Home. The institution was initially established at Parramatta in 1815 by Governor Lachlan Macquarie, as part of a range of military actions in response to the Frontier Wars and designed to suppress the so-called “hostile natives.”

The institution was relocated to Blacktown in 1823 and operated as a residential school for Aboriginal and some Maori children until 1829. Today, the site appears mostly empty and is surrounded by motorways and suburban development. However, significant gatherings and art activations are occurring on the site, which has become a living memorial to Australia’s Stolen Generations and a site for renewed Darug cultural practice. In October 2018, the site was formally handed over, with a transfer of ownership back to the Darug people, the original custodians of this land.

Extract from presentation by Corina Marino on 28 June

“I’m a Warmuli/Cannemegal woman of the Darug Nation and I’m here on behalf of my community. We’re caretakers or guardians of that area. We’re at the point where we are ready to look at the landscape and we want a living memorial at our site for those who were taken.

What we would like to take away from this workshop and larger forum is how we go about memorializing that special place. We talk about healing, and put our healing energy in to the site as a way of moving forward. We know spiritually that when we bring people onto the site, we need to protect them as well. We have ideas around how we put structure on the site. Also, the natural landscape and how we want to be able to live our culture is really important to us in that space.

What I would like to take away in these workshops is ways that you can help us honour our site and our mob. We still have children buried under houses that are further over from the site and their spirit is still there. Our old people are walking with us today; that’s our living culture.

We are privileged to be here today, for you to strengthen our walk, walking with our people.”

Extract from the presentation by group 1

“What is the spirit of the site? What does it want to be? What does it want to bring forth?”

“One of the early stories that resonated for us was about the women camping at the edge of the site, after their children were taken away from them to be kept in the institution. They could hear their children crying at night and so they would sing to their children to reassure them that it will be alright …

“It is a site of incredible institutional violence. But instead of seeing the site through the eyes of a violent act, we sought to raise up this idea of support and of resilience, this strong bond between mothers and children across the site and to try and drive our response to this remembering, a memorial treatment of the site from that perspective.”

Presented by Finn Pedersen on behalf of the working group.

Extract from presentation by group 2

“We were looking at how one might build a resilient ecology – not ecology as a return to nature, but ecology in the broadest possible sense. We felt that this is a long process that involves a considerable amount of healing, over some decades. It requires a set of steps or stages without any preconceptions about what the end result would look like, guided by what is felt to be most important by the community. You can think of this as a sequence of programming bringing a whole lot of events to the site, temporary built structures that might be vehicles for other things to happen on the site.”

Presented by Pia Ednie-Brown of RMIT on behalf of the working group.

Karla Dickens, Never Forgotten (2015), installation view, Blacktown Native Institution Corroboree, 2015, Oakhurst, New South Wales, co-commissioned by C3West on behalf of Museum of Contemporary Art Australia, Blacktown Arts Centre on behalf of Blacktown City Council and UrbanGrowth NSW.

Image: courtesy and copyright the artist

Conclusion by Carroll Go-Sam

Important information emerged from the charrettes. First, Indigenous-driven projects coalescing around contemporary responses to unresolved or ignored postcolonial histories require acceptance of dynamic interchanges, moderated by equal measures of design fearlessness and sensitivities. Second, current desires for commemorative spaces often seek a spatial presence at a scale beyond current approaches to memorializations of Indigenous social histories. Indigenous-led projects expose needs to provide spaces that not only allow public acknowledgement of trauma or histories, but also accommodate community mourning and mutual support. The Blacktown Native Institution project exemplifies how present and deep some of these histories are. This clearly defined project elicited creative responses from the intercultural mix of designers, expert participants and community representatives. The responses to this case study met articulated community goals; however, to reach these goals, participants had to be spurred on by generosity and fluid creative sensitivities. It is true that charrettes create high expectations of reaching definitive conclusions, but to achieve any meaningful end, participants had to immerse themselves in the stated problem and not be distracted by issues peripheral to the core concern, looking forward to where design futures await.

1. The Frontier Wars refer to the conflicts between European and Aboriginal peoples that began during the invasion of Australia by the British in 1788 and include battles, acts of resistance, open massacres, poisonings, forced removals and rape. Conservative estimates indicate the loss of 20,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in direct violence, and a couple of thousand colonialists. However, more recent research indicates more than 60,000 deaths. This does not include those who died from introduced disease, loss of resources, or the impact of assimilation policies and the ongoing deaths in custody, struggle for land rights and intergenerational trauma.

2. Stephen Gilchrist, “Surfacing histories: Memorials and public art in Perth,“ Artlink, vol 38 no 2, June 2018, 42–47.

Source

Practice

Published online: 16 Jul 2019

Words:

Christine Phillips,

Carroll Go-Sam,

Jock Gilbert,

Brook Andrew,

Jessica Neath,

Corina Marino

Images:

Anna Kucera,

courtesy and copyright the artist,

courtesy and copyright the artist.

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2019