Every day our inboxes and LinkedIn feeds are filled with announcements of festivals, symposiums and conferences. But what distinguishes a festival from a conference or a symposium? Following the recent announcement to cancel the 2024 Festival of Landscape Architecture (and redevelop the event’s format), we thought it important to think critically about this distinction and to reflect on the festival’s contribution over the past decade. A quick Google search reveals that a symposium is considered a large-scale meeting that features speakers who address a single topic. A conference, however, operates at a bigger scale, and is viewed as a more formal act of discussion and interchange of views, while a festival is an event or gathering that focuses on a particular theme which often reflects a unique aspect of a community (for example, an art, cultural or professional community).

The idea to start an International Festival of Landscape Architecture emerged in 2013, following a particularly tumultuous period for AILA. The festival was conceived with two purposes. First, it was intentionally planned to reengage and connect members across the country, aiming to create a positive experience in order to shift what had by then, become an organisation with a disengaged membership. Second, the festival aimed to raise the profile of landscape architecture, one of the four pillars of AILA’s Strategic Plan. As a small profession, the organisation recognised the unique opportunity to build media awareness around the festival, the conversations it created and the AILA national awards program, which moved to coincide with this significant gathering of members. The “International” branding (which was dropped in 2020) was a recognition of the broader influence that AILA members have within the Asia-Pacific region and the international reach that landscape practice and research broaches.

Musicians Simone Slattery and Anthony Albrecht performed at the opening of the 2018 AILA Festival, The Expanding Field.

Image: Photographer at Large

Review of past Festivals of Landscape Architecture thematics may mistakenly lead to the assumption that they operate as conferences, sharing similarities to the concerns of other built environment conferences, for example, publicness, climate change, urbanism and the embedding of First Nations knowledge. But it is the festival’s relationship to the community that makes it distinctive, a relationship that is largely driven by the creative directors. Through imagination, expertise, vision and energy, the creative directors shape an initial thematic (proposed through an EOI process) into a more complex program aimed at the landscape architecture community and beyond. Explore and reflect – the festivals have been a place for advancing the ideas and potential of landscape architecture influence.

Richard Weller observes that “a festival takes risk” whereas “a conference is a standardized format – a formality.” The value of taking risks is exemplified by the 2022 Country festival in Meanjin (Brisbane) curated by a team featuring Kamilaroi man Troy Casey from Aboriginal design agency Blaklash Creative. Significantly, Country gave unprecedented agency to First Nations community and practitioners. Rather than offer answers, the experience was positioned as the start of a learning process.

Kamilaroi man Troy Casey of Blaklash Creative was part of the creative directorate for the 2022 AILA Festival, Country.

Image: Tai Bobongie

The very first festival Forecast (2014) set the scene for experimentation with the event format, electing to “kill the keynote speaker” and forego multiple expensive international speakers and instead invest in “conversationalists” and multi-disciplinary panels that provided provocations and challenged conventional disciplinary thought. Outdoor long-table dinners, awards, parties and design studio visits were all included in the ticket price. This breadth of format provided more opportunities for sponsorship and attracted increased numbers, ultimately delivering a profitable festival.

Mark Tyrrell comments that “a festival leans into the social life of the conference setting, loosely structuring many events to allow maximum interaction between attendees,” whereas a stand-alone conference “puts the individual content of the presentations at the forefront with a more conservative mode of delivery and structure – the ‘sage on the stage’ and the attendees as audience.” This observation of “social life” is central to the original conceptualisation of a three-day festival developed through a range of satellite events including the AILA Fellows dinner, student research symposium, site and practice tours and the AILA national awards.

A festival develops and extends community in multiple ways, promoting new relationships between private practice, universities, government, the experienced and established, the next generation, and between designers and students. Importantly, the festival has produced a particularly productive intersection between academia and practice. Most festival creative directorate teams have involved a mix of academics and practitioners, which brings with it the support of universities in various ways. Through the act of curating, the creative directorship role has offered those who have taken up this position opportunities, as well as the chance for them to mentor others. For example, the 2016 NIMBY festival curated by Richard Weller offered seven “sub-directors” the chance to develop sessions based on their varying experiences and expertise. It also celebrated the 50-year anniversary of the institute. The Expanding Field (2018) presented a next-generation panel the opportunity to bring their diverse and fresh voices to the forum, while Forecast and The Square and the Park (2019) created student festival experiences (at a reduced price). Notably, the inaugural festival, Forecast brought AILA Fresh leaders across states together in person for the first-time.

A panel discussion at the 2016 AILA Festival, Not In My Backyard.

Image: courtesy AILA

In a further distinction to conferences, which are generally only accessible to ticket-holders, a festival consists of multiple events and sites which engage the community beyond landscape architecture. Ricky Ray Ricardo reflects: “The conference is just one part of the festival. It is the primary part that holds everything together, but a festival should offer many other opportunities to engage the public while forming partnerships with like-minded organizations.”

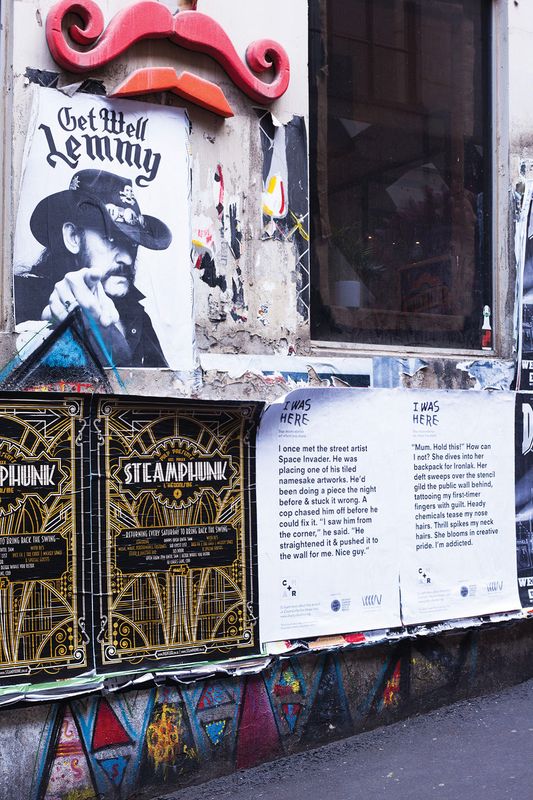

Over the past decade, there has been a remarkable array of initiatives that have taken landscape architecture into the broader public. Competitions and exhibitions have been a very successful mechanism for wider engagement. This Public Life (2015) involved the running of a student competition in collaboration with the New York-based Van Alen Institute, while The Square and the Park featured The Future Park competition (run by The University of Melbourne) and a public exhibition which produced extensive print and television media coverage. Un/Earth (2023) opened with the public exhibition Chtonic: Inhabiting the Underworld, and This Public Life in collaboration with two other organisations produced a street exhibition that featured poster work spread across the city depicting personal, place-driven stories.

The 2015 AILA Festival, This Public Life included a street exhibition that featured poster work spread across the city that depicted personal, place-driven stories.

Image: Jasmine Fisher

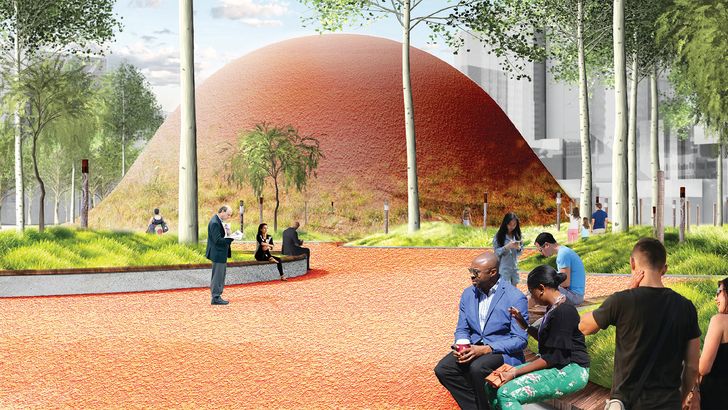

Continuous Ground by Fionn Byrne, one of the short-listed entries in The Future Park International Design Ideas Competition that was run as part of the 2019 AILA Festival, The Square and the Park.

Image: Fionn Byrne

The unexpected moment has been a distinctive festival characteristic, developed through humour, politics, and a mix of high and low culture. The performance of Where Song Began by musicians Simone Slattery and Anthony Albrecht was a moving highbrow introduction to The Expanding Field, which contrasted with Shit Gardens founder Bede Brennan’s comic introduction to “horticulturally challenged” gardens at The Square and the Park. At times the festival has become political, for example when then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull (virtually) introduced This Public Life and spoke directly to landscape architects, and during The Square and the Park whenClaire Martin led a “die-in” protest in Melbourne’s Fed Square. Most recently, Un/Earth tackled the thorny question of the “Yes” vote in an opening panel featuring Walbanga and Wadi Wadi woman Alison Page who offered a powerful clarity. In a particularly novel twist, the first festival attracted the nightly news to “forecast” the weather live from the festival.

A festival is, therefore, a conceptual umbrella, holding in place elements of a conference, an extended public program, celebrations and often symposiums. For a small profession, a festival needs to have something for everyone, operating as a valuable mechanism to bring the geographically dispersed professional community together to learn, meet, listen and have fun. The conference side of the event comprising key notes, panel discussions and debates has brought an array of international speakers to Australia. Pierre Belanger’s intense speculation on the ramifications of colonisation and extraction at The Third City (2017) is one of many memorable moments. Smaller symposiums developed in collaboration with universities on either side of the festival have allowed for more targeted academic discussions that have drawn upon visiting key notes. Success relies on synergies, including access to a range of accommodation, the availability of direct flights, a variety of venues, and, ideally, a university that has an accredited landscape architecture course.

Delegates of the 2019 AILA Festival The Square and the Park participated in a biodiversity “die-in” at Fed Square, protesting against the impacts of urban development on biodiversity.

Image: Jessica Prince

The programs of the past decade of AILA festivals can be read as a collective record of the discipline’s tensions and possibilities. Tracking the festival themes reveals a fluctuation between a tight disciplinary focus on landscape architecture (The Square and the Park, Country, NIMBY) and an expanded landscape-driven discussion encompassing other disciplines (The Third City, The Expanding Field, Un/Earth). Stretch too far and the next festival grounds the discussion in our disciplinary centre. This is the slippery world of landscape architecture – the idea of landscape is promiscuous and is shared with many others. It is because of this, that the AILA festivals have continued to be of interest to architects, artists and planners alike, along with the broader community. Above all, a decade of festivals has demonstrated that landscape architects can deliver an informative and entertaining show. What’s not to like?

A decade of AILA festivals

2014 - Forecast (Meanjin/Brisbane)

2015 - This Public Life (Naarm/Melbourne)

2016 - Not In My Backyard (Canberra)

2017 - The 3rd City (Warrane/Sydney)

2018 - The Expanding Field (Gold Coast)

2019 - The Square and the Park (Naarm/Melbourne)

2020 - Land-E-Scape: Reset - towards healing (Online)

2021 - Spectacle and Collapse (Boorloo/Perth and online)

2022 - Country (Meanjin/Brisbane)

2023 – Un/Earth (Tarndanya/Adelaide)