It is on Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung land that I meet James Wilson of Lyons and Mark Gillingham of GLAS for a tour of the long-awaited, recently completed and now multi-award-winning University of Melbourne Student Precinct. Members of the university community are setting up for the Mid-Autumn Moon Festival, with stalls, food trucks and performances planned to occupy the central amphitheatre, lawns, courtyards, and terraces.

Prior to arriving, I had received a briefing from Kirsten Bauer of Aspect Studios, whom alongside Wilson and Gillingham, cited the collaboration model between Lyons Architecture, Koning Eizenberg Architecture, Aspect Studios, NMBW Architecture Studio, Greenaway Architects and Greenshoot Consulting, Glas Urban (now GLAS Landscape Architects) and Architects EAT as the foremost innovation of the project. A distinguishing feature of the collaboration is the project’s two-year First Nations Engagement Strategy led by Greenaway and Greenshoot.

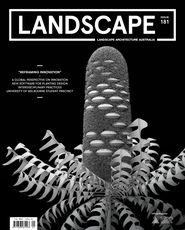

The design of the student precinct showcases the attraction and opportunities of student life.

Image: Peter Bennetts

In Melbourne, the form of collective design authorship where multiple design practices operate as if in a single studio is rooted in the 2004 redevelopment of the former Queen Victoria Hospital site. There, developer Grollo and NH Architecture brought together Denton Corker Marshall and the then emerging practices of John Wardle, McBride Charles Ryan and Kerstin Thompson, to design components of a whole city block around a network of laneways. The result is QV, an inviting and permeable precinct – distinctly “of Melbourne” - with discrete architectural identities commissioned to appear as if they had emerged over time.

In the educational sector, a similar strategy was adopted, refined and mastered by Lyons at RMIT New Academic Street, Monash College City Campus and now at the University of Melbourne Student Precinct. Landscape architects are a notable and crucial inclusion to the model and Lyons has enabled their expertise at the latter to profound effect. Here, seasoned practice Aspect and younger studio GLAS have prioritized the voices of an ambitious institution, a student body in need of opportunities for connection post-Covid, and First Nations stakeholders, into exciting new territory.

The $229 million Student Precinct occupies an area of 18,000 square metres at the heart of the university’s flagship Parkville campus, just north of the Melbourne CBD. Located between two campus gateways – a major tram interchange to the east, and an emerging train station to the south – the project was launched as the university’s “first co-created major infrastructure development” and announced as a “signature project” for the university’s Elevate Reconciliation Action Plan. The built form comprises 12,000 square metres of new landscapes, two new, and five refurbished buildings. Twenty thousand students and staff have had a say in its design.

As part of the design process, Greenaway and Greenshoot conducted over 200 consultations with approximately 130 representatives from over 45 First Nations language groups who occupied, in Bauer’s words, an “in-between space at the intersection of engagement and design.” Connection to Country is vital to Indigenous identity and the result of this process eschews traditional colonialist campus planning and design tropes. There is a clear departure from the established Parkville campus convention of treed avenues, “University Grey” brick paving, flat lawns, and stone buildings. In their place, is the deliberate erosion of a constructed ground plane, the dissolution of prescribed laneway entrances and the use of artful excavations that reveal and connect new terrain. As Bauer puts it, “We were keen to connect to country in a place where that has been obliterated. The removal of layers of building were key to creating a landscape of repair.” According to Gillingham, the design recognizes that, “there was a landform that was always here. [That] this has never been a flat site. [The] design allows you to read that topography again.”

This terrain is open, intimate, and connected. It provides spaces of prospect and refuge – across interior and exterior – in a tapestry of predominantly Victorian stone. Mansfield mudstone, Harcourt granite, Castlemaine slate and Port Fairy bluestone are interspersed with bleacher and bench seating, garden beds of Indigenous plantings, and native trees to create what Gillingham describes as a “decolonizing pavement” that extends across the landscape into surrounding publicly programmed buildings. The result is a highly connected and seamless ground plane, where the attraction and offer of student life are clearly on show.

Cascading garden beds, mudstone pavers and ponds resurface the Water Story of Bouverie Creek.

Image: Drew Echberg

Victorian stone is used to create a “decolonizing pavement” in recognition of the site’s diverse Indigenous presence.

Image: Drew Echberg

A Water Story resurfaces Bouverie Creek as a physical entity and recreates eel migration paths that have been hidden beneath years of colonial development. This is expressed in the landscape through cascading garden beds, mudstone pavers shaped to appear as if emerging from a dry spell, and ponds; and in the architecture, through rain chains (in lieu of downpipes), curvilinear interiors and watermarked carpets. There is a casualness to these spaces that is refreshing for a 170-year-old venerated institution, and markers of co-authorship and shared ownership herald a different type of student experience than what is signalled elsewhere on campus.

Twenty-four “identity bricks,” each featuring a unique object significant to its contributor’s cultural identity, have been integrated into the structure of Building 189 and further recognize the site as an Indigenous place with a diverse Indigenous presence.3 The bricks are a form of commemorative justice – “they say something very special about the Indigenous foundation of the university” says Marcia Langton, a professor at the university and Iman woman, whose suggestion for the custom of gift-giving prompted the Murrup Barak – Melbourne Institute for Indigenous Development to lead the initiative. In the courtyard of the 1888 Building, custom-etched tree grates designed by university alum and Bardi/Jawi woman Nagardarb Riches capture the six seasons of the Kulin, sitting among plants selected to promote cultural learning and reflection.

Aligned to university aspirations for a Living Laboratory, the design team collaborated with horticulturalists Claire Farrell and John Rayner from the university’s Burnley campus on plant species selection, propagation and soil profiles. Based on learnings from the Woody Meadow Pilot with City of Melbourne at Birrarung Marr, a low nutrient soil substrate was supplied by academics to support the growth of native plants while suppressing weeds. Further work undertaken by native botany expert and Ngarigo man, Charles Solomon, has ensured that plants from all 45 Indigenous language groups represented in the student cohort are planted across the site. At the Student Pavilion rooftop, robotically farmed garden beds and an Indigenous kitchen garden provide further testing grounds for innovation and additional points of Indigenous connection. While the at-ground elements, at the time I visited, were mostly thriving, their rooftop counterparts have been less successful – with sparse, underperforming planting highlighting the need for ongoing specialized stewardship.

Plants from all 45 of the Indigenous language groups representedin the student cohort are used across the landscape.

Image: Drew Echberg

The design team worked with Indigenous artist Nghardarb Francine Riches to integrate her drawings that depict observations of nature signals from the six Wurundjeri seasons into tree grates.

Image: Drew Echberg

The University of Melbourne Student Precinct offers a compelling template for truth telling and reconciliation at campus or city scales, one that prioritizes years’ long processes for listening, learning, exchange – and importantly, the respectful gestation and realization of ideas. At the influential intersection of city and campus, this project and future others like it, have a vital role to play in challenging existing notions of place and democratic participation. In the wake of a failed referendum for an Indigenous Voice to Parliament, projects need to be bolder and more impactful in debunking the myth of terra nullius.

With sunset closing in, our tour concludes with the sight of students celebrating China’s Mid-Autumn Festival, Japan’s Harvest Moon Festival, Korea’s Chuseok, and Vietnam’s Tet Trung Thu. The Student Precinct is significant for the pathway it charts towards a new typology of civic landscape – one in which genuinely diverse and engaged collaborative processes can give rise to unexpected and unique outcomes that are inclusive, equitable and firmly rooted in an Australian sense of place.

Plant list (abridged)

Eucalyptus scoparia (Wallangarra white gum), Acacia pendula (weeping myall), Brachychiton rupestris (Queensland bottle tree), Corymbia citriodora (lemon-scented gum), Corymbia citriodora ‘Scentuous’ (dwarf lemon-scented gum), Corymbia ficifolia (red flowering gum), Corymbia maculata ‘ST1’ Lowanna (compact spotted gum), Eucalyptus caesia ‘Silver Princess’ (Silver Princess caesia), Eucalyptus pauciflora (snow gum), Eucalyptus sideroxylon (red ironbark), Ficus platypoda (desert fig), Livistona australis (cabbage-tree palm), Melaleuca quinquenervia (broad-leaved paperbark), Asplenium bulbiferum (hen and chicken fern), Austrostipa nodosa (tall spear-grass), Banksia integrifolia ‘Roller Coaster’ (coast banksia), Billardiera longiflora (purple apple-berry), Carpobrotus rossii (pig face), Chrysocephalum apiculatum (common everlasting), Correa alba (white corera), Correa baeuerlenii (chef’s-hat correa), Darwinia citriodora (lemon-scented myrtle), Dianella caerulea ‘Little Jess’ (Little Jess dianella), Dichondra argentea (Dichondra Silver Falls), Dicksonia antarctica (soft tree fern), Dodonaea viscosa ‘Purpurea’ (purple hop bush), Enchylaena tomentosa (ruby saltbush), Ficinia nodosa (knobby club-rush), Gahnia sieberiana (red-fruit saw-sedge), Goodenia humilis (swamp goodenia), Hardenbergia violacea ‘Meema’ (purple coral pea), Hibbertia scandens (snake vine), Hymenosporum flavum ‘Gold Nugget’ (dwarf native frangipani), Indigofera australis (Austral indigo), Juncus pallidus (pale rush), Kennedia prostrata (running postman), Leucophyta brownii (cushion bush), Lomandra longifolia ‘Tanika’ (spiny-head mat-rush), Microseris lanceolata (yam daisy), Myoporum parvifolium (creeping boobialla), Ozothamnus diosmifolius (sago bush), Pandorea pandorana (wonga wonga vine), Patersonia occidentalis (long purple-flag), Philotheca myoporoides (long-leaf wax flower), Ptilotus spathulatus (pussy tails), Pycnosorus chrysanthes (billy buttons), Scaevola aemula (fairy fan-flower), Spyridium parvifolium ‘Edna Walling Nimbus’ (Edna Walling nimbus), Xanthorrhoea minor (small grasstree), Xerochrysum palustre (swamp everlasting)

Credits

- Project

- The University of Melbourne Student Precinct

- Landscape architect

- ASPECT Studios

Australia

- Project Team

- Aspect Studios: Kirsten Bauer, Tim Fowler, Georgia Babidge, Dermot Egan, Bradley Clothier, Christian Riquelme, Ian Rooney, Warwick Savvas, Robert Williamson, Marti Fooks, Srivani Manchala, Ankit Chauhan, Angela Arango, Xiao Lin and John Williams, Glas Urban: Mark Gillingham, Phil Harkin, Bryan Choong, Marina Pizzotti, Hilary Hoggett and Jenny Tin

- Landscape architect

-

GLAS Landscape Architects

- Consultants

-

AV consultant

UT Consulting

Acoustics engineer Marshall Day Acoustics

Architects in collaboration Koning Eizenberg, NMBW Architecture Studio, Greenaway Architects, Architects EAT

Builder Kane Constructions

Building surveyor and access consultant McKenzie Group Consulting

Cultural advisor Greenshoot Consulting

ESD consultant Aurecon

Facade engineer Alto BMG

Fire engineer Dobbs Doherty

Heritage consultant Lovell Chen

Project leader Lyons Architecture

Project manager Donald Cant Watts Corke

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia

Services engineer Lucid Consulting Australia

Structural and civil engineer WSP

Sustainability strategy Breathe Architecture

Theatre planner Schuler Shook

Traffic engineer GTA Consultants (now Stantec)

Wayfinding ASPECT Studios

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung people.

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 12 months

Construction 29 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens, Universities / colleges

- Client

-

Client name

The University of Melbourne

Source

Review

Published online: 3 Apr 2024

Words:

Jocelyn Chiew

Images:

Drew Echberg,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2024