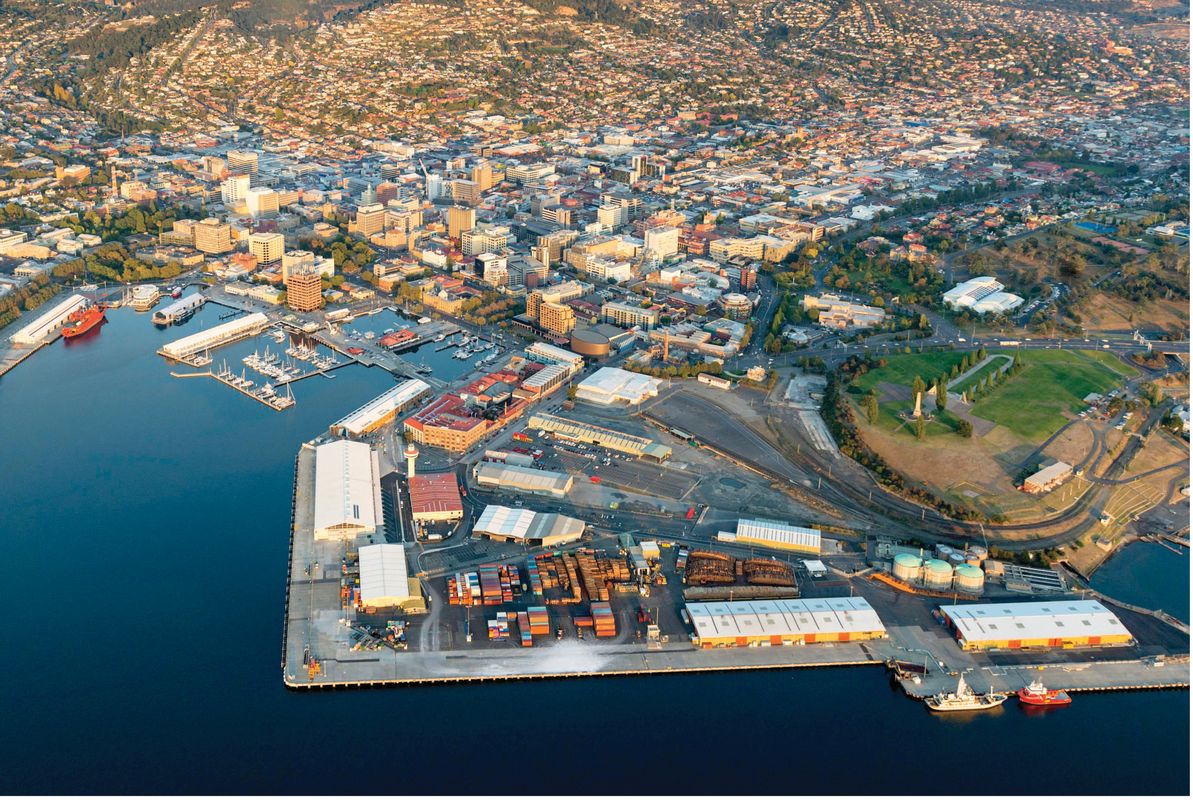

Mac Point is a 9.3-hectare government-owned waterfront site on the Port of Hobart along the eastern edge of the inner city. The site is surrounded by water to the north, east and south and, like Hobart itself, is defined beautifully by the water and mountains. The revered Hobart Cenotaph sits on the escarpment immediately to the north, and historic buildings are clustered to the south-east, along the city edge. The opportunity to any urbanist or “city-maker” seems obvious. Here lies the only remaining chance to extend a very contained inner city with a new waterfront quarter that boosts the local knowledge economy by expanding existing scientific research, education and commercial facilities, increasing inner-city housing supply, and providing new civic public spaces in compact fine-grain urban forms conducive to sustainable transport. The government-owned nature of the site, as well as its large size and prime location, also paves the way for ambitious benchmarks to be set for social and environmental outcomes – benchmarks that are far more difficult to achieve on smaller, privately owned sites.

This opportunity seemed obvious to the Macquarie Point Development Corporation (MPDC) in 2012 when it articulated the vision for a “vibrant, liveable and sustainable place that optimizes economic, social, environmental and aesthetic outcomes that complement [the site’s] surrounds, enhance connectivity, and offer a range of opportunities to live, work, invest and play.”1 Of course, such motherhood-type statements need to be further articulated through a series of planning phases; and a strong start was made with the preparation of detailed background studies and design guidelines by Leigh Woolley Architect and Urban Design, John Wardle Architects, Taylor Cullity Lethlean, Inspiring Place, 1 Plus 2 Architecture and Village Well that would underpin a masterplan for a mixed-use precinct demonstrating the emerging urbanity of Hobart.

Detailed planning and urban design investigations undertaken from the early 2000s established a set of planning and urban design controls for Macquarie Point. In 2016, those controls were integrated into the Hobart City Council’s Sullivans Cove Planning Scheme 19972 (Amendment 2/2015). In November 2016, the Tasmanian Government appointed MONA to shape the public space component in what would become the “Reset plan.”3 Under the plan, MPDC changed its relationship with the wider community, understanding that community and stakeholder engagement were central elements of its business. A series of 20 briefings for various stakeholder groups was conducted to generate understanding and receive feedback on the planning scheme amendments required to facilitate the plan.

However, a series of delays occurred in the competitive bid process with the result that none of the shortlisted development submissions were ultimately realized, nor was MONA’s vision for the Point designed by Fender Katsalidis and Rush Wright that had, at the time, been embraced by stakeholders and the wider Tasmanian community. This scheme incorporated a “Truth and Reconciliation Art Park” with cultural and public spaces sitting alongside Antarctic research and science facilities, a conference centre, hotels, retailers and residential uses.

MONA’s vision for the redevelopment of the Point included a “Truth and Reconciliation Art Park,” Antarctic research and science facilities, a conference centre, hotels, retail spaces and residential uses.

Image: Fender Katsalidis, Rush Wright and Scenery

A series of sandstone outcrops in the centre of the public space in MONA’s scheme for Macquarie Point.

Image: Fender Katsalidis, Rush Wright and Scenery

Instead, on 3 May 2023, the Tasmanian Government signed an agreement with the AFL for the establishment of a Tasmanian-based AFL and AFLW Club. A stadium is proposed to occupy the lion’s share of the Mac Point site in what will be a perplexingly inward-facing event space for such a scenic waterfront inner-city location. The height and bulk of the proposed architecture contravenes all previous site plans and ambitions. As noted above, Macquarie Point falls under the Sullivans Cove Planning Scheme, which has seen several planning amendments, but none have included a stadium. Stadiums do not generate the intensity of daily activity needed for an inner-city district to be successful. In fact, in the words of a former MPDC board member, they do the opposite, by sterilizing the urban environment around them with large spaces required for crowd control and event operations.4

How did this happen? The desire for a stadium did not originate from the community and stakeholder consultation process. The option did not come from a strategic planning department of the Tasmanian Government or the City of Hobart. There appear to have been no robust studies undertaken on what the impact of a stadium in this location might be on the city, what alternate locations were considered, and how they were evaluated. There has been no review of the planning and urban design principles established in previous detailed investigations. It appears this was the result of a political deal between the AFL and the Tasmanian Government.

Political courting of a Tasmanian AFL team had been increasing in previous years with a seemingly unexcited AFL. However, in 2022, a deal was struck in which the AFL agreed that a Tasmanian team could be established. This deal included the proviso that a new stadium must be built and the location for this new stadium must be Macquarie Point.

Plans for the stadium advanced quickly. Understandably, many were outraged. Two MPs resigned from the Liberal government in protest and, as independents, demanded the contract be made public.5 The contract revealed the level of risk the government was willing to absorb to claim the political creation of a Tasmanian AFL team. Labor, the Greens and most independents remain opposed to the stadium.

This is unfortunately not a unique example of a political decision brazenly trumping due process in Australian large-scale urban renewal projects. We saw it at Barangaroo in Sydney when a second casino license was controversially approved, along with its location, through a legislative change without any reference to urban planning frameworks or urban design implications.6 We saw a stadium built at the waterfront in Melbourne Docklands in 2000 without any reference to the City of Melbourne’s strategic planning work. Harbour Esplanade could be the public space heart of Docklands, yet strung between the stadium and the water’s edge, it remains a “sterile” place, despite several activation attempts over 24 years.

Large-scale urban renewal is a very complex undertaking that requires many layers of expertise targeted towards agreed goals. These layers need to be coordinated under a governance structure with clear roles, responsibilities and decision-making processes that operate with transparency and accountability. What happened at Barangaroo, Docklands and now Mac Point shows how the planning process can fail without a robust governance structure. We see planning change after planning change, and influential powerbrokers taking advantage of the apparent flexibility to manoeuvre for private gain.

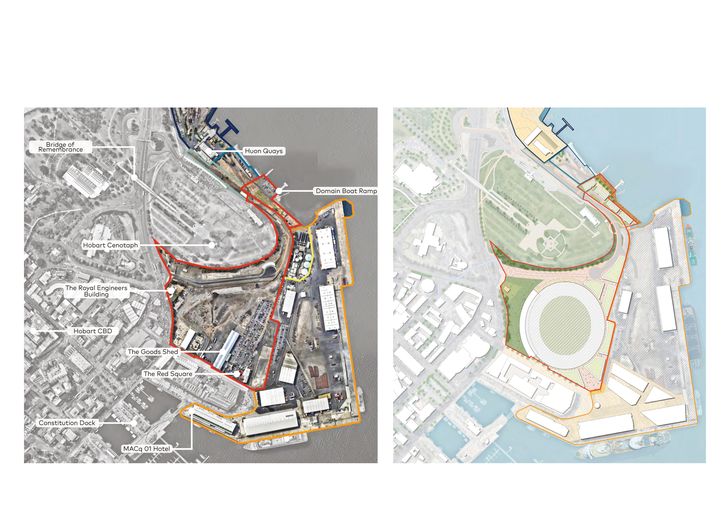

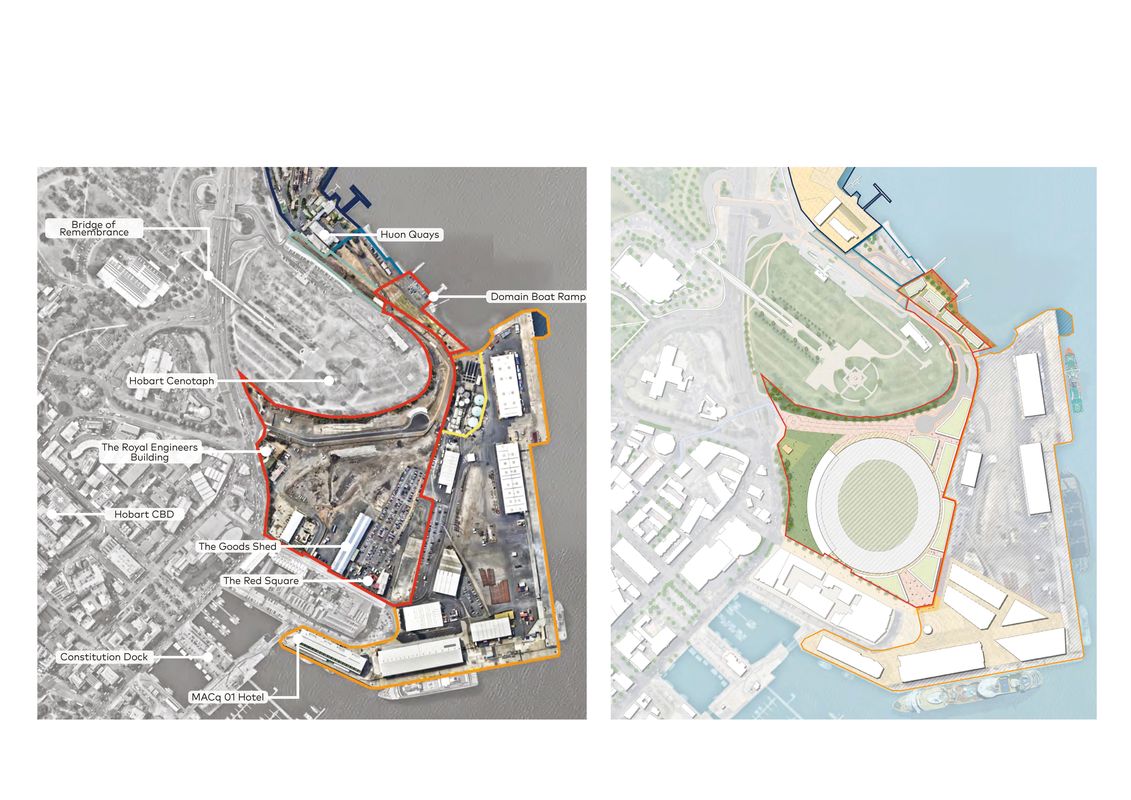

Left: Plan showing existing conditions at the Mac Point site. Right: Plan showing proposed Mac Point stadium, located immediately behind the cluster of waterfront heritage buildings. The Goods Shed that was retained and repurposed in all previous plans is slated for demolition to make way for the stadium.

Image: Mac Point Draft Precinct Plan (October 2023)

What does good practice globally look like?

If we were to follow global good practice, the high-level aspirations articulated in the Macquarie Point Development Corporation Act 2012 would have included a set of legislated concrete outcomes as non-negotiables with a governance structure ensuring sightlines to achieving these. Importantly, the process would be protected by political opportunism with arm’s-length decision-making principles that do not allow ministers to override decisions at their discretion. The project would maintain alignment with existing planning frameworks by following established approvals processes for the precinct, the building and the public domain projects. This alignment is critical to maintaining certainty, consistency and fairness for investors, developers and communities.

The local city government would play the lead role in site planning and design.7 This would begin with joint or majority ownership of the corporation with at least 50 percent board representation and flow through to approvals processes with reference to city-wide frameworks for urban form and public domain. State governments are sometimes necessary on these projects in relation to linked transport infrastructure, such as new metro or tram lines, or due to historic ownership patterns. They often stay involved and sometimes receive lease payments for ongoing use of land. However, when it comes to planning and design, the best examples are led by city governments, who are a natural fit, from both a capabilities and experience perspective, for place-based urban outcomes and community engagement.

Lastly, the better examples of these types of projects around the world leverage the site to address established social or infrastructural deficits of the city. In other projects, we see metro and tram lines being financed with development proceeds, 20-to-60 percent affordable housing components, new or expanded universities, national or state-level scientific institutions, museums, and performance venues, and all are integrated into a complementary urban environment that breathes life into the city on a daily basis.

Sites such as Mac Point present rare opportunities for integrated city expansions that can address a diversity of interlinked urban ambitions appropriate to and supportive of a bustling inner-city district. Replacing this opportunity with a stadium is not a good solution for urban “revitalization” and, if the stadium is built, Hobart will lose this opportunity for generations.

1. Macquarie Point Development Corporation, 2014. Macquarie Point Development Corporation Annual Report 2013–2024, Tasmanian Government, https://www.macpoint.com/reporting

2. City of Hobart, 2023, Sullivans Cove Planning Scheme, https://www.hobartcity.com.au/Development/

Planning-schemes

3. Macquarie Point Reset Masterplan 2017–2030, https://www.planning.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/705997/Applied-adopted-or-incorporated-document-Macquarie-Point-Reset-Masterplan-2017-2030.PDF

4. Debra Berkhout, 2023, “Contested Megaprojects – Who gets to decide? A case study of Macquarie Point, Hobart,” panel discussion at the Festival of Urbanism, University of Sydney, https://www.festivalofurbanism.com/events/fou2023/contested-megaprojects-who-gets-to-decide-a-case-study-of-macquarie-point-hobart

5. Tasmanian Government, 2023, “Signed agreement with the AFL released” (press release), https://www.premier.tas.gov.au/site_resources_2015/additional_releases/signed-agreement-with-the-afl-released

6. Four Corners, 2021, “Packer’s Crown Casino Gamble: A tale of big money, lobbying and political influence,” ABC, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wtwWWHj0W7g

7. Mike Harris, 2019, “Australian cities pay the price for blocking council input to projects that shape them,” The Conversation, https://theconversation.com/australian-cities-pay-the-price-for-blocking-council-input-to-projects-that-shape-them-127017