I usually ride my bike to work, but in the last few weeks before parental leave, I have been catching the tram. If you look around you on the tram on a morning commute, you’ll find it difficult to see anyone without a digital extension of themselves in their hands – head down, peripheral vision almost shut off, swiping away in the digital realm. As we depend on our digital appendages more and more, we are at risk of becoming increasingly disconnected from the specifics of place, from the natural world and from the contextual inputs that stimulate our senses.

One of the risks of designing in digital is the ability to produce at ever-increasing speeds. Although, as landscape architects, efficiency is important for our viability in practice, it can be to the detriment of our relationship with the very medium with which we work. As landscape theorist Anita Berrizbeitia observes, “landscape architects must engage in patient observation and slow learning to deepen their knowledge of living systems and organisms to heighten their capacity for visceral and emotion perception, and to develop the analytical skills required to detect orders and relationships that can potentially be translated into the design of exceptional experiences and places.”1

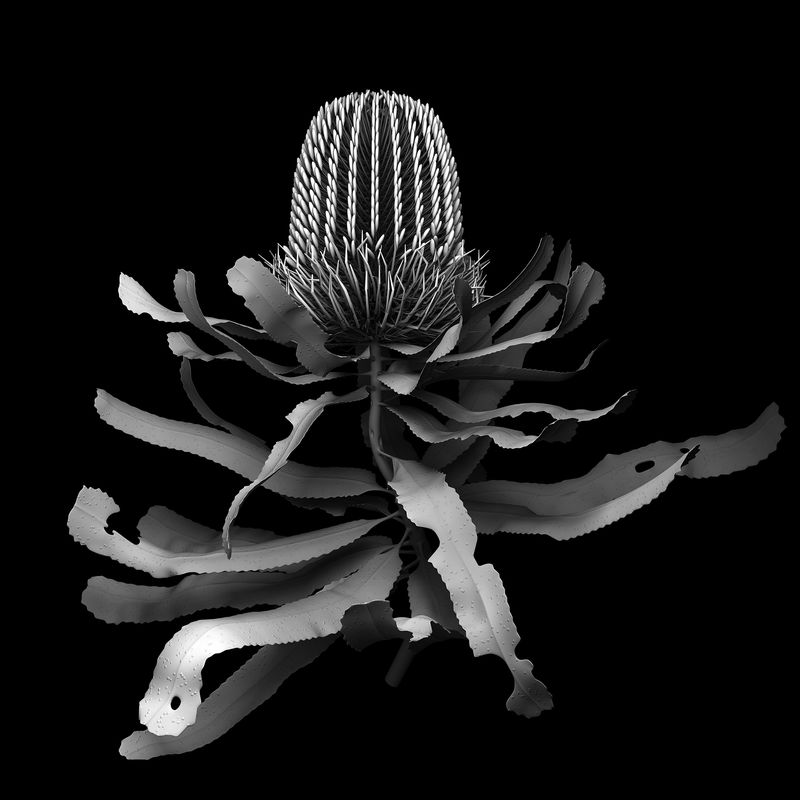

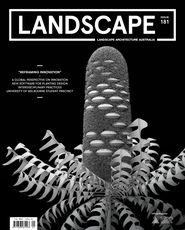

In their near-perfection and suspension in abstract space, Henderson’s prints allude to the dangers of relying too much on digital representations and processes; banksia ericifolia/2019.

Image: Garth Henderson

Artist Garth Henderson’s process reveals some of the new possibilities available through the visual intersection and immersion of reality and technology, and the ability to reflect on – and appreciate – the natural world through the digital and art. The activity of observing plants – an ability built up over many years of being in the garden – as well as the painstaking process of digitally sculpting species to form intricately detailed studies, are central to his practice.

Henderson’s digitally produced botanic prints alert us to the ways our profession’s increasing reliance on digital design processes and representation may create opportunities for advocating for an appreciation of the natural world. As more of our design process is playing out in the digital realm, we landscape architects risk succumbing to this disconnection from the conditional, imperfect and contextual reality of the places we work with. While the discipline has much to gain from in the digital realm, Henderson’s prints allude to the dangers of relying too much on digital representations and processes. The sublime beauty of his works – their near-perfection, textural abstraction and suspension in abstract space – speaks to the uneasiness of depending on the digital as a method of appreciating our natural surrounds.

Henderson has a background in horticulture, photography and printmaking, and his works represent a contemporary take on botanical illustration that focuses on form and geometry, rather than precision and texture. His interest in the relationship between plants (in particular, banksias) and mathematics can be traced back to his childhood in the south-west corner of Western Australia. He locates a defining moment in his artistic approach to his time working in a specialist cacti and succulent nursery in Perth, where he was exposed to a generous collection of xerophytic plants and grew a specimen of Lophocereus schottii var. monstrosus – in his words, “a deviant mathematical example, Brutalist in context, of a plant stripped to the bare minimum of features for survival.” The amalgamation of experiences and this pivotal moment were influential for Henderson in defining his approach to “representing flora as shapes and patterns.”

His childhood in the south-west corner of Western Australia and his work in horticulture have driven Henderson’s creative practice. A photograph by Henderson of a Lophocereus schottii var. monstrosus plant.

Image: Garth Henderson

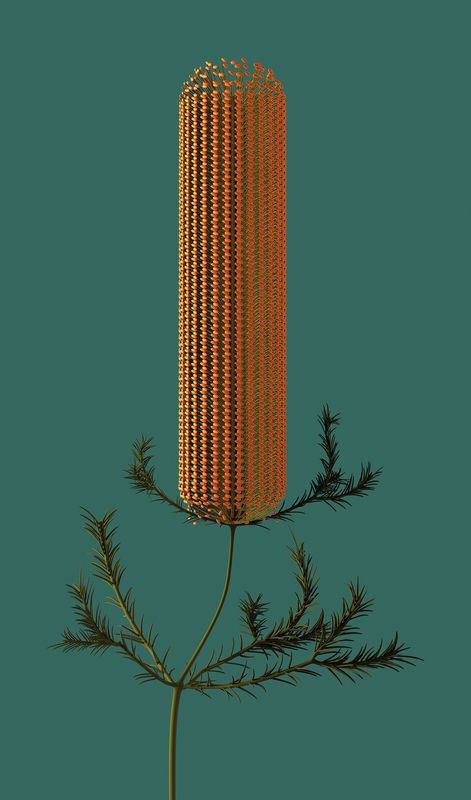

The works produced via this process, such as fire lily_Gloriosa superba/2023, are uncanny in their depiction of botanical forms. Petals, leaves and anther lack texture. Veins, striation and indents have been omitted. The specimen is suspended in space, often on a black background, without shadow and reflecting light in an unnatural way. Defects, damage and decay are ignored and the rendering produces an extraordinarily smooth and reflective surface that reminds one of a metallic object. Henderson describes this as “using the tools of the unreal to call people’s attention to the real.” He notes that his choice around the lighting “dictates the successful ability to ‘perceive,’ or at least ‘suspend disbelief,’ when viewing 3D works.”

Henderson’s use of hyperreality produces an abstract perfection that prompts discussion of the ways that representation can produce landscape; fire lily_Gloriosa superba/2023.

Image: Garth Henderson

Here, I raise the alternative position: impact and risk for landscape architecture. One of the issues we face in practice is a tendency to value appearance over relationship, performance or function. We sell our ideas to clients using enchanting renders, our awards judging is heavily based on photographs, and we can bypass technical and social challenges if we work in the digital realm, divorced from bodily contact with a physical and cultural context.

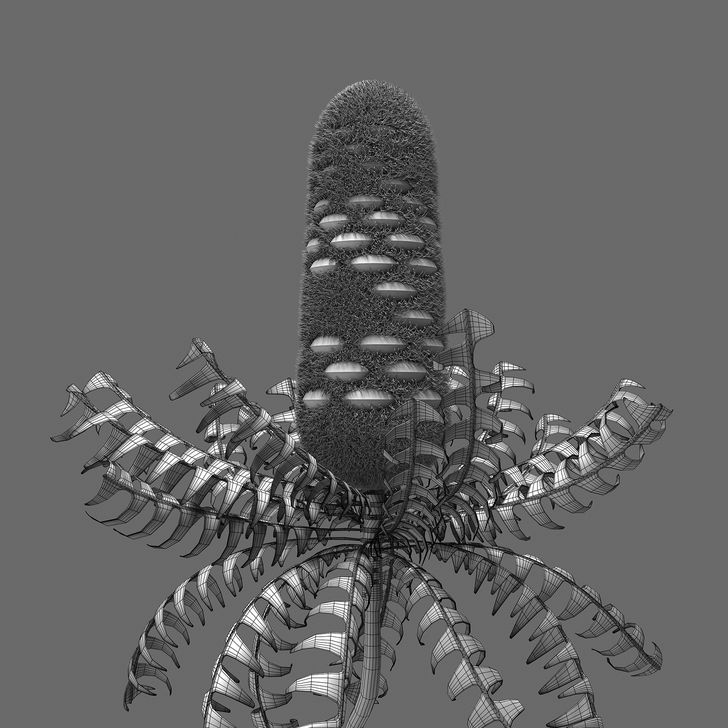

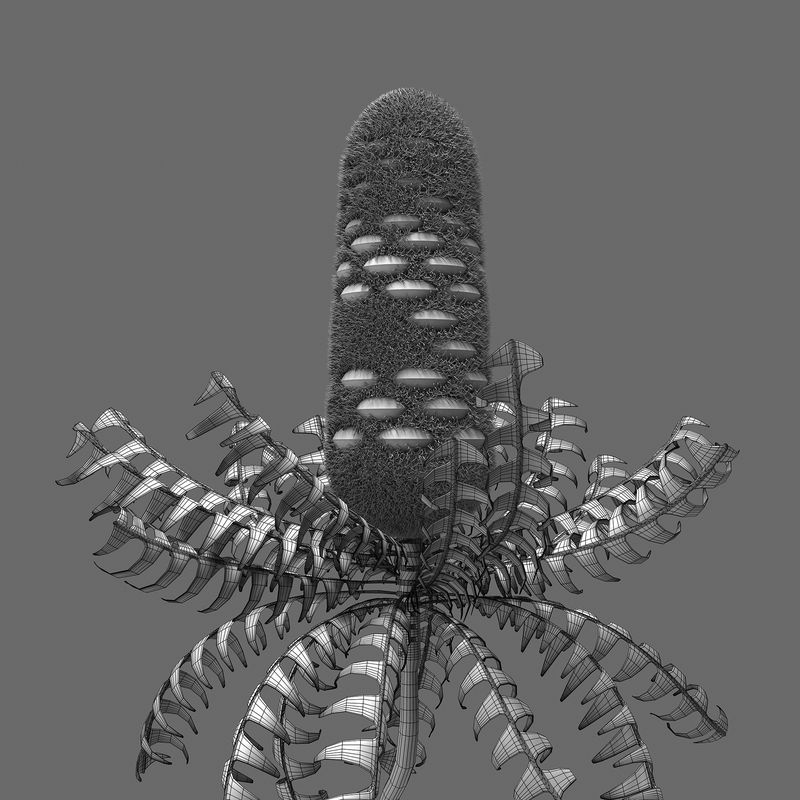

In constructive_botanics_banksia/sketch06, the wireframe linework is exposed, revealing the artist’s process and drawing the viewer’s focus to the traits of the plant.

Image: Garth Henderson

Henderson’s use of hyperreality aims to, in his words, “enable a visual shortcut to recognition.” It produces an abstract perfection that ignores the conditions, temporality and decline that are inherent to the natural world, and provokes discussion around expectations and the ways that representation can produce landscape. This expectation of perfection and the static, “maintained” nature of a plant ignores the opportunities for appreciating cycles of life and growth, succession and the dynamic, contextual implications of place. Works such as constructive _botanics_banksia/sketch06, however – rendered in greyscale, with wireframe linework exposed – reveal some of the artist’s process and draw the viewer’s focus to the visual traits of the plant rather than the expression of a living being that interacts with its context. Henderson’s works, then, suggest opportunities for representing form, scale and geometries without implying a cultural, contextual or social narrative. Perhaps we can learn from these techniques to differentiate between design exploration, design representation and design marketing.

1. B. Cannon Ivers (ed.), 250 Things a Landscape Architect Should Know (Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2021).

Source

Practice

Published online: 17 Apr 2024

Words:

Jess Stewart

Images:

Garth Henderson

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2024