“An excellent design is where you can’t tell where the landscape architect has been.”

Some version of this statement is often used to describe the spirit of landscape architecture. While it captures aspects of our design practice, this position leads to complications when it comes to questions of authorship, particularly in an increasingly competitive professional environment where designers must demonstrate a range of expertise. Issues of authorship become even more fraught in the contemporary multidisciplinary project. Historically, it has been relatively straightforward to trace the authors of single spatial typologies, such as the garden or the park. But in the multidisciplinary project, which is shaped by ideas, politics and power, questions of design authorship become murky. In this context, landscape architecture’s other much-cited framing as “the art of time” leaves it particularly vulnerable when considered against an explicit architecture output tied to static and object-driven concepts of design authorship.

Too often, the significant contributions of landscape architects are being overlooked in project reviews, design histories and industry awards. For example, a recently published review of a large-scale urban design project in Melbourne acknowledged the historic role of a landscape architect whose work had been erased by this new design, yet failed to recognize the contemporary landscape designers who had clearly contributed significantly to the design (as evidenced by the accompanying photographs, which showcased more landscape than architecture).

In our own academic work, we have experienced first-hand how the power dynamics of multidisciplinary consultancies work against landscape architecture authorship. A couple of years ago, we undertook a small research project looking at how the engineers, architects and landscape architects collaborated in digital practice to design a large-scale infrastructural project. Interviews with the three disciplines involved confirmed the success of the approach, which we wrote up accordingly. On requesting the use of images, the client sent our paper to the “lead consultant” for sign-off. The principal of the architecture firm (not the architects in the firm who had worked consistently on the project) then proceeded to edit the paper to establish himself as the sole designer of a complex multimillion-dollar project. In his mind, everyone else simply developed his initial (very preliminary) idea and he would not release images unless we changed the paper to follow his narrative. We published the article without images.

On top of denying individual practice contributions, these examples demonstrate how design histories and professional knowledge are skewed based on who is the “gatekeeper” of design authorship. Just today, we read a social media post in which a well-established landscape architect thanked an architect for acknowledging their role in a project that had been profiled by The Guardian. With no professional recourse, it seems landscape practitioners are reliant on the goodwill of architects to acknowledge their contribution. Some architects are better than others.

This edition of Landscape Architecture Australia was initially provoked by what appears to be a shared professional frustration around recognition. However, as we started to explore ideas of authorship more widely, we realized the value of this lens for thinking afresh about contemporary landscape architecture practice.

A principal tension arising around landscape architecture’s claims to authorship (conceptually and legally) is that authorship is aligned with a static art/design practice. And rarely does our practice fit into this category. For example, a 2008 copyright case in North America concerning the design of a wildflower garden concluded that while the design was original, “a living garden lacks the kind of authorship and stable fixation normally required to support copyright … Simply put, gardens are planted and cultivated, not authored.”1 According to this ruling, landscape architecture’s ambition to design with living systems would void copyright and authorship.

At the heart of the problem is that all landscape architecture is co-authored with the natural world and is continually shaped by cultural forces. Time is a distinguishing trait of our practice, but an enemy when it comes to recognition of authorship. Drawing on this tension, this edition explores in more depth the inherently collaborative attributes of contemporary landscape practice.

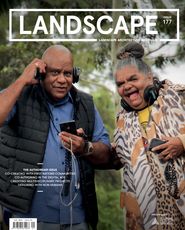

We begin with a focus on new practices of co-creating. We put the spotlight on the seven-year multi-authored process that led to the Yalinguth app featured on the cover. Working across three Aboriginal-led organizations and two universities, and held together by the “glue” of Storyscape, this project demonstrates how creative and technical expertise can aid First Nations communities in sharing their own stories on their own terms.

What happens when a designer co-creates with another species or an environment? We explore how an increasing interest in post-humanist design is shaping novel approaches to artificial habitats and leading to the recognition of rights for environments, such as rivers and the Moon. An interview with Singapore-based landscape practice Salad Dressing demonstrates how these new ideas can be introduced in the commercial sphere.

We dig more deeply into the culture of co-authorship, exploring for example the all-encompassing influence of the digital as an authoring partner, as both a source of information and a generative design influence. Along the way, we offer landscape practices some therapy and advice for achieving recognition of their work. What are your legal or moral rights for recognition and how should the contemporary multidisciplinary project be reviewed to acknowledge the role of multiple authorship? What consultation should we expect when our designs are altered and changed? And finally, we explore the rise of the identity of Chinese landscape architects, who are emerging from a silent discipline embedded within design institutes into a more diverse set of practices, ideas and knowledge.

In job interviews, candidates are often asked, “What is your greatest weakness?” Various strategies are used to turn a weakness into a positive attribute – for instance, in the classic response, “I work too hard.” While initiated from a point of frustration, the engaging and inspiring content of this edition demonstrates that our perceived professional weakness of lacking recognition is in fact an indicator of our strength. We are collaborators who position our contributions within a longer and more diverse continuum than a professional canon. In the current environmental and cultural state of the world, the single-authored design idea has little relevance.

– Jillian Walliss and Heike Rahmann, guest editors

1. Jani McCutcheon, “Natural causes: When author meets nature in copyright law and art. Some observations inspired by Kelley v. Chicago Park District,” University of Cincinnati Law Review, vol. 86, no. 2, 2018, 711, scholarship.law.uc.edu/uclr/vol86/iss2/6

Source

Practice

Published online: 18 Jan 2023

Words:

Jillian Walliss,

Heike Rahmann

Images:

Kongjian Yu, Turenscape

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2023