Balls Head juts south into Sydney Harbour from the sleepy lower-north-shore suburb of Waverton. The body of the headland is formed of the city’s ur-material of weeping sandstone, its stony armature cloaked beneath an impressive canopy until it tumbles exposed and unbroken to the waterline. Balls Head Reserve occupies the peninsula’s southernmost tip, where the area’s thin waist opens to a wider headland: a shape, if you were a winged thing, resembling a hammer or a mallet. Ordinary tools, but capable of imposing surprising force.

The reserve is made conspicuous by contrast with its neighbours. Across Balls Head Bay to the east stands Blues Point Tower, symbol of Seidler’s ultimately rejected plans for a modernist utopia. Diagonally opposite lies Balls Head Reserve’s “sister” headland, Barangaroo Reserve, re-moulded to reference an imagined past while erasing another.1 Ballast Point Park2 occupies the closest headland on Sydney’s southern shore, where the relics of industry acquire the romance of ruins.3 The site itself is backed by two recent projects, The Coal Loader4 and Carradah Park5, both inviting public access after being excluded by decades of industry, curating stories of the working harbour within parkland settings. In this context, the humble Balls Head Reserve sits at an unexpected nexus, quietly yet strategically centred, occupying a prime position from which to observe the ever-evolving surrounding foreshores.

Historically, we are familiar with the way the conceptual language of political affiliation can become physically affixed to place. Bodies of water and their banks provide compelling metaphors for ideologies staked to geography. In a European context, it’s the way the banks of a city like Paris can come to stand for opposing ends of a linear political spectrum (Left Bank, Right Bank).

At Balls Head Reserve, well-used concrete walkways follow the original paths laid down in the 1930s on this hybrid (both natural and designed) site.

Image: Mark Cocquio

Sydney’s harbour is a drowned river valley, its former tributaries swollen to bays, its ancient ridge lines rising above the tide as peninsulas and promontories. Here, the water curls into secreted coves, carving a line more looping than linear, and peninsulas extend into the fray like hammers or fists: protruding, concealing, demanding. In this way of reading topography for signs, each headland might come to stand as a kind of intellectual lighthouse – guarding and guiding positions in relation to the treatment of landscape.

Though discreet in size, the site of Balls Head Reserve is able to provide that rare thrill available to Sydney as a gift of its setting, delivering the sense that within the urban fabric there exists places spared the impacts of European settlement. Sites like Balls Head Reserve are places where an alternate story of the city can be imagined, a misleading lineage where the landscape evolved in the absence of colonialism’s violent effects. This mirage holds a seductive allure over the city.6

It’s revealing to consider the nature of projects that come to mind when asked to review and critique. Especially if, as a landscape architect, one finds one’s self also attracted by this mirage, drawn to spaces that appear undesigned over the heroic gesture. As a designer, to be drawn to these places can feel like an act of renunciation of our very professional role. Perhaps its pertinent then to interrogate this attraction, to unpack the affinity. To reflect on practice can be akin to staring into a kind of professional mirror, one which returns personal pet peeves and hang-ups in an endless feedback loop. Yet what attracts us, what holds our attention, is as likely to confront as it is to comfort. For a landscape architect, the understanding that no site is “untouched” doesn’t negate the attractive power of places like Balls Head Reserve, but should instead deepen and inform it. This understanding assesses the value of a site like Ball’s Head Reserve by its ongoing history of collective civic action and care, rather than by the promotion of a picturesque fantasy.

Lush now, the site was earlier stripped of its vegetation, becoming almost bald by the 1930s, as its stands of timber answered the needs of the Great Depression. Even then, during a time we don’t now perceive as being particularly ecologically sensitive, the site’s destruction caused consternation, and the city’s citizens, from the artists to the ordinary, responded in kind. In 1916, Henry Lawson penned a lament entitled The Sacrifice of Balls Head, decrying that “The State is cutting down Balls Head … To make a wharf for coal.” Substitute coal for casinos or apartments and his protest becomes current, one voice in a long chorus contesting the city’s northern foreshore in its endless tousle between public and private interests.

Tunnels being constructed for the Balls Head Coal Loader.

Image: courtesy Stanton Library Historical Services

Artists’ eyes have always watched the peninsula, with some 150 works dating from the fledgling settlement to the twentieth century documenting and responding to its transformation. Lloyd Rees, one-time local, captured the site like many of his fellow artists – from the water. His series of sketches, dating from 1931 and now held by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, depicts the headland looming over calm waters, its stony back exposed to the sky, its form shorn clean and stripped bare. Rees was known for his artistic license, often adding a scenic bough to strengthen a composition, so the images are striking for what they lack. They provide a jolt when seen by anyone familiar with passing the site by water now, an image of a different, alternative Sydney, in an area now blurred by vegetation regrowth. The drawings capture the result of the Depression’s privations, its physical manifestation in the landscape.

What isn’t captured in these images is the story of the site’s afforestation, a rare story of civic concern and collective action. Tree ferns and Christmas trees were planted by members of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Waverton Progress Association in 1931, while 2,000 people showed up on a Saturday afternoon in the same year to plant even more trees on the same site. Members of the Naturalists’ Society of New South Wales planted stands of blackbutt the following year. Nearly a century on from these plantings, it’s hard to imagine that anybody ferrying by the site now would consider what they see the result of concerted action, rather than preservation – the act of erosion applying as equally to civic memory as to the foreshores themselves. This forgetting has implications. If we forget that what we value today is something we both imagined and actively created, rather than something that was saved, then we relinquish the agency possible in proactive engagement with place.

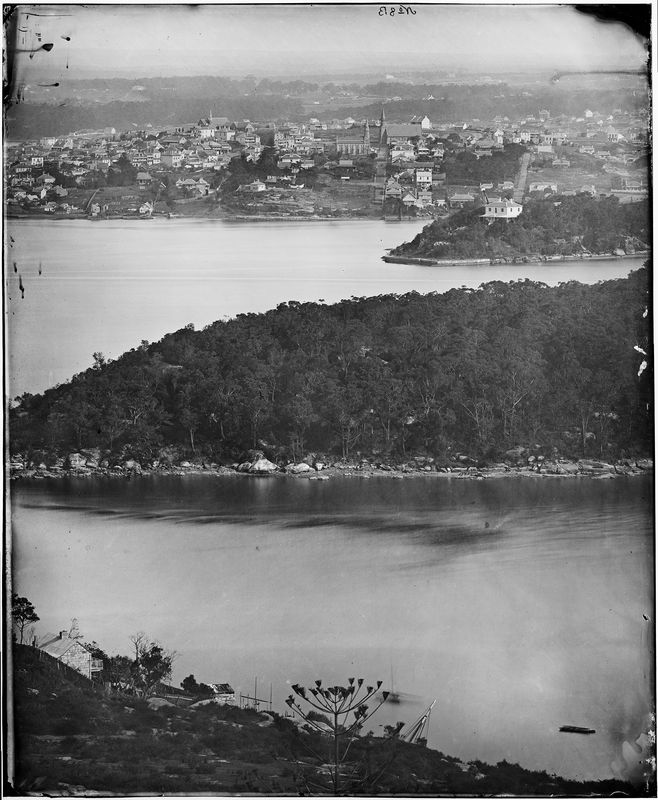

The view across Balls Head to Birchgrove, circa 1870–1875.

Image: American and Australasian Photographic Company. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

What does it mean when a site’s living processes erase evidence of the site’s planning, its deliberate and conscious creation? Would a landscape architect consider this in a measure of its success? Perhaps the question, focused on the recognition and remembrance of action, of intention, is too petty. For an often misunderstood profession, these hybrid sites, both natural and designed, in the act of collective forgetting, may subtly evidence the vocation’s strange strengths. As a project centred on one of the most direct of tasks involved in working in the landscape – planting trees – this small site persuasively speaks to what it can mean to design as a landscape architect. A practice with the potential to be less defined by the desire to impose a singular will upon a site and more inclined to invite a conversation with place over time. A conversation able to continue beyond the duration of a singular project and one that may forget the names of those who initiated it – time erasing the individual act, but bequeathing a collective legacy.

Balls Head Reserve is located on the land of the Cammeraygal people.

1. Richard Weller, “Barangaroo – can it work?”, Landscape Architecture Australia, issue 127, August 2010, https://architectureau.com/articles/can-barangaroo-work (accessed 21 April 2022).

2. Ballast Point Park was designed by McGregor Coxall and Choi Ropiha Fighera for Sydney Harbour Foreshore Authority.

3. Laura Harding and Scott Hawken, “Ballast Point Park,” Landscape Architecture Australia, issue 124, November 2009, https://landscapeaustralia.com/articles/ballast-point-park-3 (accessed 10 March 2022). This author’s intention is to pose the question of the issues and complexities inherent in the romanticization of industrial ruins and relics here, rather than to resolve this issue.

4. The Coal Loader Centre for Sustainability was designed by Hassell for North Sydney Council.

5. Carradah Park/Former BP Site Park was designed by McGregor Coxall for North Sydney Council.

6. Barangaroo is described as a “once-scarred promontory … now visually reunited with Goat Island and its sister headlands at Balls Head, McMahons Point and Ballast Point”. [Barangaroo Delivery Authority, Barangaroo website, https://www.barangaroo.com/visit/barangaroo-reserve (accessed 13 March 2022).]

Source

Practice

Published online: 13 Oct 2022

Words:

David Whitworth

Images:

American and Australasian Photographic Company. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW,

David Whitworth,

Mark Cocquio,

courtesy Stanton Library Historical Services

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022