In 2017 an almost kilometre-long park constructed on a stretch of redundant highway was opened in the centre of Seoul. Design blogs and media across the world disseminated the Dutch design practice MVRDV’s inspiration for the scheme. Claiming the park as “South Korea’s answer to New York’s High Line,” the design website Dezeen outlined Seoullo 7017’s major design features, including an urban arboretum with plants organized according to the Korean alphabet and set in a vast array of circles, combined with the requisite urban programs.1, 2 MVRDV’s co-founding director Winy Maas describes the garden as “human and friendly and green,” offering approaches typical of European city planning. However, he claims a “science fiction element” as an Asian reference, stating that “in Asia they want to dip their cities in this super-green feeling that comes from science fiction, from movies like Avatar .”3

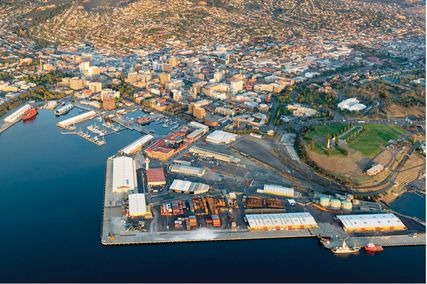

From Peter Walker to Winy Maas to Rem Koolhaas, we have become accustomed to European and North American designers defining the potentials of our new world cities. As an Australian academic I followed with disbelief the design for Barangaroo Reserve, which uncritically proposed the reconstruction of a “natural” headland. Like MVRDV’s design in Seoul, the Barangaroo scheme by PWP Landscape Architecture (USA) with Johnson Pilton Walker has been spruiked in international design blogs and magazines, and was nominated as a finalist in the 2016 Rosa Barba Awards International Landscape Prize and more recently was awarded the American Architecture Prize 2017 Landscape Design of the Year. While fresh eyes can certainly be useful, we are often dealt cultural generalizations rather than provocative insights, as iconic designers country hop, spending just days in complex economic, political and cultural contexts. As one of my students pointed out in relation to Maas’s science fiction observation: at least reference Asian science fiction (preferably without Scarlett Johansson).

According to Winy Maas, co-founding director of Dutch office MVRDV, the design for Seoullo 7017 was inspired by science fiction.

Image: Ossip van Duivenbode

It is time to turn the tables on European and North American designers (and academics) and to begin to celebrate and promote the skills and innovations of homegrown designers, thinkers and critics. Their dominance is not just felt through the “iconic” designs sprinkled around our cities, but also in their prominence at conferences and in design publications that are framed as “global.” For instance, in 2016 the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF) held a landscape summit in Philadelphia, the USA, with the ambition of producing an international landscape declaration fitting for this century. Out of the seventy-five summit speakers only two were from Asia. While Australia accepts and even celebrates its peripheral position, it is impossible to deny that Asia is now the global centre, experiencing the fastest growth in urbanization, economy and population, and, returning to landscape architecture, the most rapid developments in the profession.

Asian countries represent diverse cultural, political and economic contexts that offer fascinating and, at times, challenging influences on how spaces and ecological systems are conceived, delivered and used. The complexity and scope of work emerging from the region is currently not represented in academic discourse, international awards, practice, publications or curriculum. The International Federation of Landscape Architects (IFLA) Asia-Pacific Region awards program, run for the first time in 2017, provides a valuable starting point for developing knowledge of an emerging contemporary Asian practice. More than one hundred entries were received, with projects in Thailand, New Zealand, China, Japan, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Taiwan, Singapore, Australia and South Korea. This valuable collection of projects now invites greater scrutiny and discussion.

The reflections of international alumni and PhD students at the University of Melbourne (where I teach) and RMIT University regarding contemporary practice in Singapore and China suggest that in both countries there is a maturing and dynamic discipline that is growing less reliant on international designers. Throughout the 2000s, the Singaporean government employed many high-profile designers to work on significant nation-building projects such as Marina Bay Sands by Safdie Architects and Gardens by the Bay by Grant Associates and Wilkinson Eyre. Twenty years on, this reliance on international expertise is waning, replaced by Singaporean designers and thinkers in key government agencies (including the National Parks Board) and universities, and the rise of internationally acclaimed regional design practices such as WOHA.

Damian Tang, the president of IFLA Asia-Pacific Region at the time of writing, returned to Singapore a decade ago, after completing a double degree in architecture and landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne. He took a summer job at the National Parks Board in Singapore with the intention of later returning to Australia, but opportunity led him to stay. He observes that Singapore has been far better served by international designers than many other Asian contexts due to the opening of local Singapore offices. This long-term commitment by practices such as Grant Associates and Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl has positively contributed to the profile and development of landscape architecture in Singapore. In contrast, the more common “fly-in fly-out and advise from abroad” approach of international designers leaves the local firms to deal with all the difficult issues. He nominates the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park designed by Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl as one of the best examples by an international firm, observing that it is far more challenging to work within the existing urban fabric of Singapore than the tabula rasa reclaimed land of Marina Bay.

Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park in Singapore, designed by Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl.

Image: Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl

Singapore seems now to be in the position to reflect on its achievements and capitalize on the lessons learnt from the wide range of design and planning projects delivered over the past years. The enormous capacity of the Singapore government, which features strong intergovernmental department relationships, offers a sound platform to continue to refine approaches and strategies. Tang believes it is time to consolidate the extensive portfolio of completed projects by supporting the local population to actively engage and take ownership of these considerable investments. This act will raise the value of these projects and contribute new layers of meaning to the city. Looking to the broader Asian region, he sees Singapore’s influence on many countries, particularly China in the last two decades. He comments that while Chinese landscape architecture is embracing ecologically ambitious infrastructure, he feels that certain Chinese design approaches are still “missing the soul/heart of people.”

Turning to China, language issues make it extremely challenging for those outside the country to comprehend contemporary landscape architecture practice. For more than twenty years Kongjian Yu and his firm Turenscape have been “the Chinese voice” of contemporary design to the west – for instance, he was one of the two invited Asian speakers at the LAF summit. But what of the next generation of Chinese designers?

On graduation, many young Chinese landscape architects find work with the extensive number of developers delivering large-scale residential schemes across China. Eileen Zhang, who graduated from Beijing Forestry University in 2010, began her working life with Pubang, China (PBCN), a leading investment and development company founded in 2003. She comments that the rapid rate of delivery and the need to regulate quality and costs encouraged design approaches reflective of particular styles such as “European” or “South-East Asian,” reproducible as a branded product. However, she observes that with the slowing of the residential market over the past three years, emphasis has moved to investing in public projects such as parks, civic spaces, schools and river upgrades. This has also encouraged specialization within landscape firms in areas such as waterscapes (sponge city/rain gardens), lighting or playground design.

New Chinese landscape architecture firms are offering alternative models of practice. Importantly, the slowing of economic development and longer delivery timeframes means that practices have more potential to engage with the community – offering the opportunity to bring the “soul/heart of the people” into design. As Zhang observes, working in the fast-paced development model meant it was impossible to engage with the public or revise schemes.

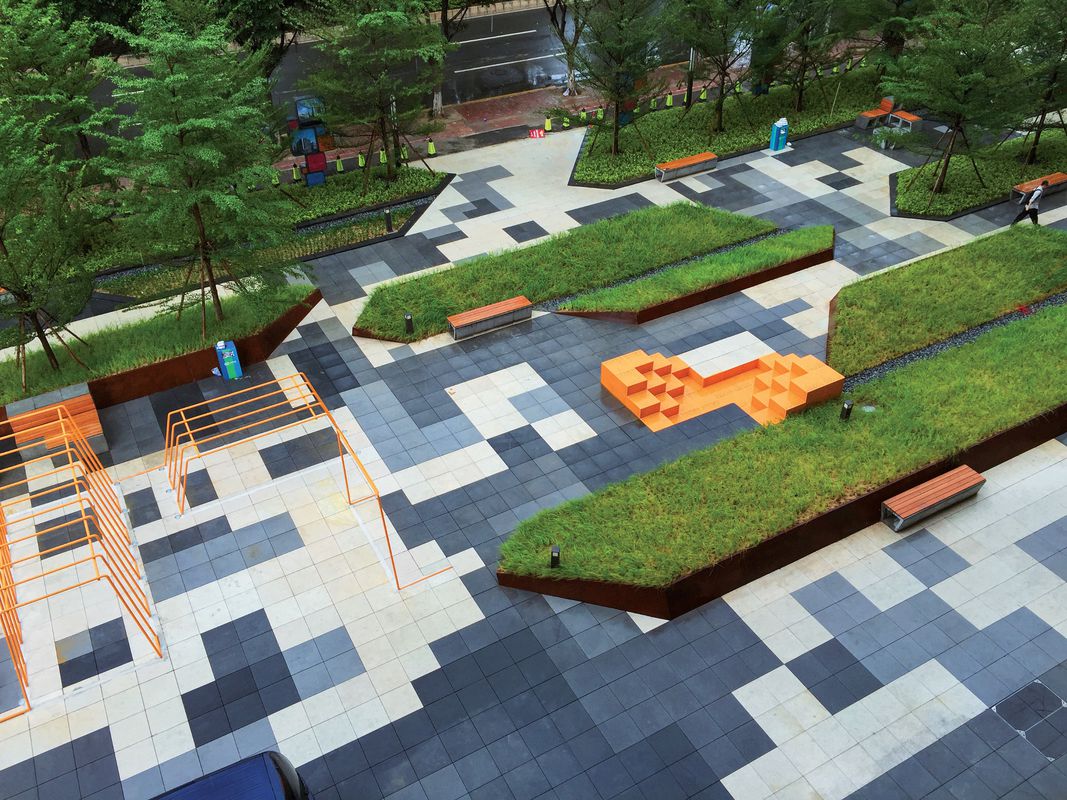

The firm D+H (Design Plus Hope) is one example of a new-generation Chinese practice. The three principal design directors have a mix of international and Asian tertiary education, along with practice experience at American and European firms. Beginning in an office in Los Angeles in 2011, the firm has expanded to Shenzhen and Shanghai. Established as an interdisciplinary design practice, D+H is driven by a strong social agenda committed to delivering positive change through the power of planning and design. Its ambition to improve the lives of people represents a major shift in design priorities from those that drove the Chinese economic market.

Vanke Cloud City Phase 2 MiCool Display Area in Guangzhou, China by D+H.

Image: D+H

Similarly, Z+T Studio, founded in Shanghai in 2009 by Dong Zhang and Ziyang Tang, offers an innovative practice model, incorporating a landscape design atelier, art workshop and a biophilic lab. The practice is committed to working across ecology and community wellbeing and bridging Eastern and Western perspectives. The addition of the art workshop in 2014, which includes fabricators, engineers, contractors and designers, significantly increased Z+T Studio’s capacity to engage with materiality and fabrication processes, as evident in its Yueyuan Courtyard design completed in 2016. Located in the historic canal city of Suzhou, the courtyard contains a beautifully crafted water feature carved into granite stone, reflective of water processes.

This brief discussion highlights the evolving state of landscape architecture in China and Singapore, as well as the rapid increase in local capacity and expertise. As Zhang comments, China’s fast development process has produced a generation of designers and project managers who have extensive project experience. Equally the introduction of international offices into Singapore helped foster the local landscape profession and raise design ambitions more generally across the Asian region.

Australia has an important role to play in supporting this unfolding terrain of contemporary Asian landscape practice. Asian students form a critical component of our university alumni. Landscape architecture programs should be working actively with alumni beyond the boundaries of Australia, offering support to a next generation of landscape practitioners and recognizing achievement through roles such as adjunct professorships, and invitations as guest speakers and to hold exhibitions. Further, our programs could take a closer look at their curriculum, which is largely derived from Euro-North American perspectives, and consider a repositioning to reflect our place in an emerging Asian design culture. This includes encouraging stronger Asian representation in our conferences and seminars. As Tang half joked, perhaps we could hold a conference themed around “Asian solutions for Australian cities.” In a refreshing change, Landscape Architecture Australia is presenting a one-day symposium in May 2018 that focuses on the topic of “Sharing Local Knowledge for a Global Future,” with speakers from Singapore, South Korea, India, Thailand and New Zealand. There is no question that there are many exciting designs and practice models emerging from Asia. From a global perspective, we need to work harder to uncover them, and more specifically from an Australian outlook, we need to recognize the considerable benefits of engaging more comprehensively with the region.

Footnotes

1 . Jessica Mairs, “MVRDV transforms 1970s highway into ‘plant village’ in Seoul,” Dezeen website, 22 May 2017, dezeen.com/2017/05/22/mvrdv-seoullo-7017-conversion-overpass-highway-road-park-garden-high-line-seoul-south-korea (accessed 3 October 2017).

2 . Amy Frearson, “MVRDV to transform Seoul overpass into High Line-inspired park,” Dezeen website, 13 May 2015, dezeen.com/2015/05/13/mvrdv-studio-makkink-bey-transform-seoul-overpass-into-high-line-inspired-park-seoul-skygarden (accessed 3 October 2017).

3 . Rowan Moore, “A garden bridge that works: how Seoul succeeded where London failed,” The Guardian website, 20 May 2017, theguardian.com/cities/2017/may/19/seoul-skygarden-south-korea-london-garden-bridge (accessed 3 October 2017).

Source

Practice

Published online: 31 May 2018

Words:

Jillian Walliss

Images:

D+H,

Hai Zhang,

Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2018