Bruce Mackenzie was a doyen of the profession of landscape architecture in Australia. His practices, Bruce Mackenzie and Associates (BMA) and Bruce Mackenzie Design jointly spanned more than fifty years. He was a reflective practitioner who valued empirical and practical knowledge and had an unshakeable conviction that good design sense must, first and foremost, consider the essential attributes of the Australian environment. Always the innovator and tireless campaigner, Mackenzie led from the front for the profession of landscape architecture and the public alike.

Born in Paddington, New South Wales in 1932, Mackenzie spent his childhood years leading an independent lifestyle, exploring Sydney’s metropolitan landscapes in the broadest possible sense. Traversing those parts of the city that were natural, those that were urban, as well as those that were degraded or gritty, Mackenzie pursued improvised activities that encouraged resourcefulness in response. He attended Sydney Boys High School, yet his family’s circumstances made it impossible to go to university or to study for a professional career. Mackenzie entered the printing industry as a graphic designer. As a young adult, he engaged in immersive nature-based activities, including canoeing, bushwalking and rock climbing – all of which expanded his appreciation of the Australian landscape.

The 1960s were a time of burgeoning environmental awareness in the wake of the huge impacts of the post-Second World War development boom. It was in response to this that the profession of landscape architecture in Australia emerged. Mackenzie played a crucial role in the establishment of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA, 1966), subsequently serving as National President from 1981 to 1983. He was a powerful advocate for the use of Australian native plants in landscape design. Mackenzie criticised the design of the landscape of Canberra under international design motifs, believing it to be a missed opportunity for Australia’s coming of age. In response, BMA’s commissions were always consciously responsive to site and context and unequivocally promoted the indigenous landscape and its conservation.

Bruce Mackenzie, when National President of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, conducting a tree planting ceremony at the occasion of AILA’s hosting of the XX IFLA World Congress in Canberra in 1982.

Image: Ralph Neale

At Kuring-gai College of Advanced Education (1972) BMA had as their medium a rocky plateau of remnant bushland located alongside Lane Cove National Park and its distinctive Hawkesbury sandstone formations. The studio’s early analyses helped inform the extent of building footprints and areas of indigenous vegetation to be protected during construction. In a design strategy that would be replicated in countless subsequent works, public and private alike, BMA sought to carefully integrate architecture and site, envisaging the off-form concrete buildings amid the site’s geology, so that the buildings would appear to “grow” from the site.

The planting for the Kuring-gai campus was guided by the appearance of naturalness. BMA ensured random placement for new plantings and experimented with re-seeding techniques that might result in facsimiles of indigenous vegetation. Detailed missives to grounds staff saw BMA micro-manage the site with the aim of keeping as much bare rock surfaces exposed as possible. The visual effect this produced Mackenzie later espoused as “alternative parkland” for the way his studio’s approach contravened how things at that time were usually done.

BMA ensured that the buildings of the new campus of Kuring-gai College of Advanced Education would appear to ‘grow’ from the site.

Image: Andrew Saniga, 2016

A series of landscape reclamation projects further established BMA’s approach as well as its notoriety. Two waterside parks on Sydney Harbour’s foreshores stemmed from a clean-up operation in preparation for Queen Elizabeth II’s visit to open the Sydney Opera House in October 1973. Peacock Point (later Illoura Reserve) in Balmain (1973), and Long Nose Point (now Yurulbin Park) in Birchgrove (1977) were hailed for the dramatic visual impacts that resulted from the strategies BMA deployed in the sites’ transformations. Striking before and after photographs were used in the promotion of the profession at the time.

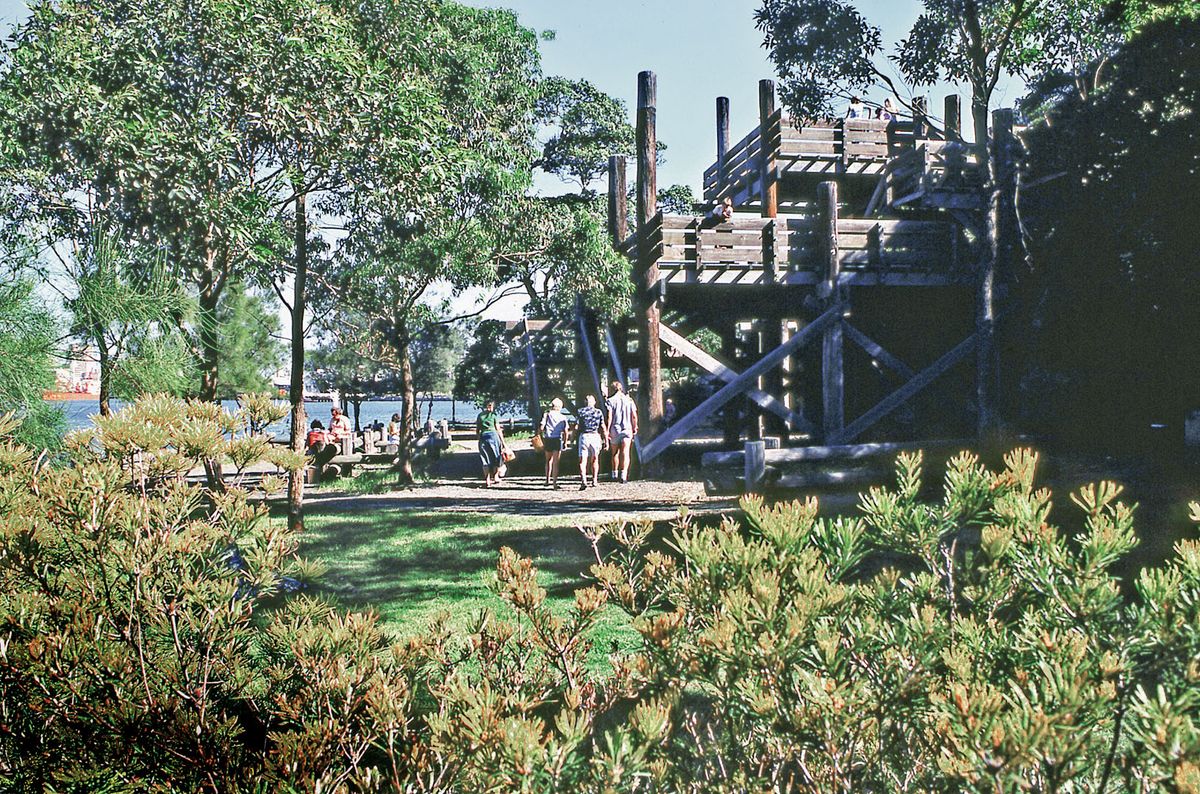

Long Nose Point (now Yurulbin Park) in Birchgrove, New South Wales.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Peacock Point (now Illoura Reserve) in Balmain, New South Wales.

Image: David Moore

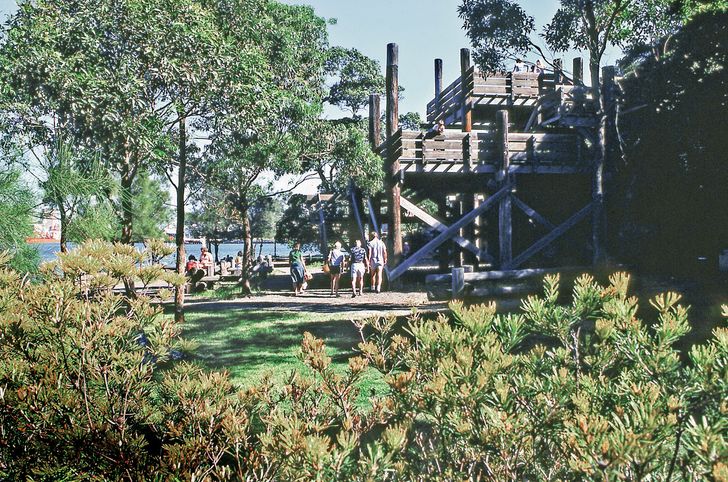

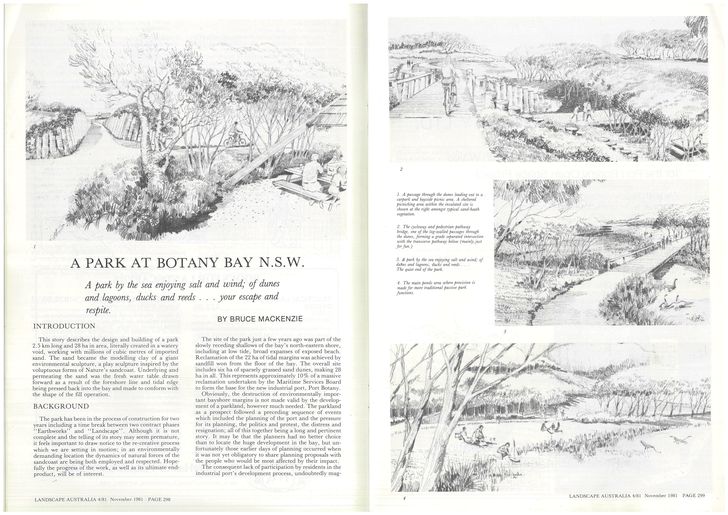

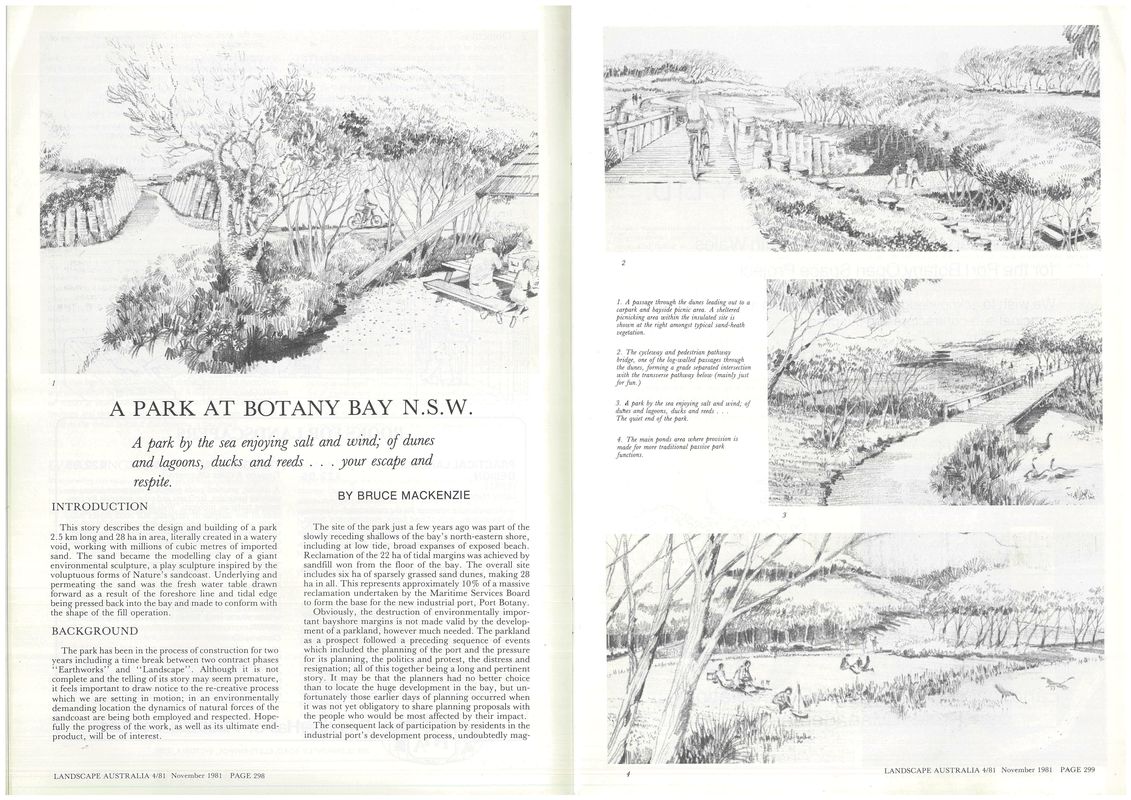

One of BMA’s most monumental works was a new foreshore park in Botany Bay. The park was created in response to the development of an industrial port and associated arterial freeway. Sir Joseph Banks Reserve (1986) saw BMA play a key role in repairing degraded tidal margins and reconstructing an entire coastal sand dune ecosystem. The massive 28 hectare reclamation and remodelling exercise was also designed to sustain carefully choreographed recreational experiences. Complex engineering and innovative landscape techniques enabled the park to thrive upon a substrate of pure sand dredged from Botany Bay.

Mackenzie realised that in order to create a better built environment, landscape architects needed to influence government at both the state and federal levels, and he consistently did this throughout his entire life. He was also very aware of the need for the built environment professions to work together, aligned toward a common goal of “sustainability in the first instance and quality of life in the second.”1

Sir Joseph Banks Park at Botany Bay was a feat of landscape design engineering and for its time.

Image: Landscape Australia, No. 4, 1981

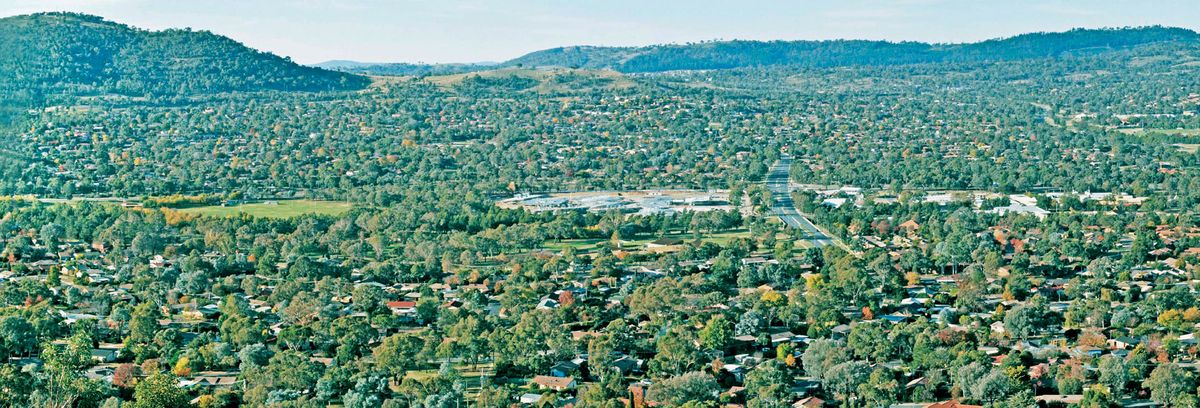

Kambah, ACT, where Bruce Mackenzie achieved the building of a central parkland.

Image: courtesy Bruce Mackenzie

In showcasing his lifetime’s work in his book Design With Landscape in 2011, Mackenzie reflected on his practice’s expansive range of commissions. These covered the design of large urban parklands, urban design projects, private gardens (including for Australian embassies in Bangkok and Paris), infrastructure projects, university campuses, and residential subdivisions at the large scale, including Kambah in Tuggeranong in the ACT, where his distinctive Australian style made an indelible mark – creating, as he put it, a “new olive-green image for modern Canberra.”2

His attendance at the 2023 AILA Festival of Landscape Architecture in Adelaide is but one example of his unerring work ethic and commitment to landscape architecture. Known for his outspoken conviction and consistent bid for excellence, it seems fitting to conclude with his own words: “… I have wrestled with these ideas, been tortured by disappointments and richly rewarded by success. And in the process never stopped being rigorous, testing my beliefs to confirm truths.”3

To read a collection of short reflections contributed by members of the Australian built environment community, go here.

1. Bruce Mackenzie, 2011, Design With Landscape: a 50 year journey, BruceMackenzieDesign: Sydney, p 11.

2. Ibid. p 283.

3. Ibid. p 10.