Landscape Australia: Chloe, tell us about Camperdown Memorial Rest Park and the grasslands at the cemetery there. What drew you to that site?

Chloe Walsh: I live around the corner, so it was a place that I was going to very regularly, especially in COVID. The cemetery itself has these remnant grasslands, which I didn’t really know about until I started to do these longer walks through the cemetery. There was this strange spatial juxtaposition between the park and the cemetery, because the park itself used to be part of the same cemetery, but they removed the gravestones. There was this really interesting tension … the spatial conditions had been changed based on the way that it had been maintained.

The site also sits on what used to be the Kangaroo Ground, which connects Camperdown and University of Sydney, and that was an area where First Nations people would hunt kangaroos, hence the name, obviously a European name. We think of Sydney as this lush, sandstone place, but at this point, which is quite close to the city, it has this history of this relationship with grasses, which has been determined by how they have been cared for. I became interested in what our relationship with tending and maintenance is in the city.

Is there any signage about the grasslands at the cemetery?

CW: There’s a very small laminated sign that is faded and hidden; it’s not very prominent. That was where this audio guided walk that I developed came about.

This cemetery, it’s kind of an anomaly in the city because of its colonial and historical context, being one of the earliest in Sydney. The landscape has been left to do what it likes, but it’s because it’s been classified as a cemetery, as a historic cemetery. There’s this other story of the landscape that hasn’t been as acknowledged as it could have been.

I had been doing this physical work in the cemetery with the local “Friends of” group. As we were picking apart the weeds, the coordinator from the local council, Helen Knowles, was instructing me and telling me the names of the species. It was a really vivid way of learning about the species and their habits, much more memorable than reading about the species in a scientific journal. I wanted to extend that experience to local community members.

A snippet from a 10-metre-long drawing made for Grassland Tales, which follows two cycles of growth and dormancy.

Image: Supplied

What do people hear when they go on the audio guided walk? Where do you take them?

CW: It’s very loosely guided; I start off with the context of the landscape, the geological history, and how that has dictated all of the plants that live in the place. Everything starts with geology. I talk about how narrative shapes the way that we understand landscape. When we emphasise story about landscape, these places become more memorable in different ways. I was also looking at the loose principles of Shinrin Yoku, or forest bathing, so it was about being this meditative experience. It was about slowing down in the site and beginning to notice the subtle things.

I was spending so much time there, and if you’re just hanging around with a camera, people often begin to chat to you. I was having conversations with people who would come to the place more or less every day or every week, and there were things that they didn’t know about the site that they were really interested in. And so, it was about developing different ways to view the subtle parts of the landscape. The more you look, there’s always more to discover and appreciate, even in such a dense suburban inner-city place. It feels like a little haven of overgrown lush greenery.

Grassland Tales as a project appears to be less about a finished landscape design, and more about the process, where the landscape architect’s role is to encourage the community to tend to an ever-changing parkland. Could you explain how that works?

CW: I’m interested in the role of community in the care of landscape, especially public land. There are certain tensions that come with a community stepping in. I was initially looking at Bushcare models, which have an emphasis on endemic native species, but I was also interested in these other plants that exist in urban environments, the spontaneous ones. In the discipline, a lot of people have embraced more novel ecologies, or spontaneous ecologies, but it was the community that was complaining to council when the grass was growing too long. There’s this separation between how we want to move in the discipline and how the the public is receiving the work that we’re doing – or not doing.

The grasslands begin to take on a new role culturally and ecologically within the site; mown pockets for humans to sit, the larvae of an Orange-Streaked Ringlet (Hypocysta irius) breakfast on a basket grass (Oplismenus aemulus) leaf, conversations alongside seed collection of longhaired plume grass (Dichelachne Crinita).

Image: Supplied

If the community are going to embrace it, they need to have some agency in it. The benefit of grass and herbaceous species is that they grow so quickly. You can do something, and if people don’t like it, or it doesn’t really work, you can change it. It can be this really quite fast, iterative model.

I love your drawings of people picnicking, with the grasses all around them. Could you describe what the experience of using this park would be as it changes?

CW: Much of the project stemmed from La Niña bringing so much rainfall. In a lot of the inner-west parks, the grass got way too long, and it was too wet for the council to mow – there was a new level of dynamism and liveliness to the parks themselves. Occasionally it would dry off, and, in that time before the council could get to the park to mow, people were sitting in amongst the long grass. At times, they mowed a small section in the centre that allowed people to inhabit it, if they weren’t interested in getting into the long grass.

In a design sense, actively deciding the areas to mow or the areas that would be seeded with native grasses would allow for many different spatial outcomes without drastically changing the park itself. For that to change and evolve over time would be super interesting.

The proposed mowing practices in your project reminded me of the Catalonian practice Marti Franch’s project Girona’s Shores … were there any precedent projects that influenced you?

CW: Yes, EMF [Estudi Martí Franch] and even Julian Raxworthy’s work with “the viridic,” these focuses on tending and care have influenced me a lot. Tim Waterman talks about the genius temporum, instead of genius loci, the spirit of a place, adapting that to be genus temporium, capturing the temporal changes, and the changes in seasonality and time.

So yes, with EMF, I think the ethos is very similar. But where [Girona’s Shores] was about stripping back, pulling back certain parts of this very overgrown area, with my project, it’s already such a stripped back area, so it’s about allowing the landscape in a little bit more.

Weeding within Camperdown Cemetery requires careful attention, untangling plants from one another to remove the eager invasives.

Image: Supplied

What are some of the grass species included in the project, and what sort of animal life might they support?

CW: The existing native grassland is a themeda-, a kangaroo grass-heavy grassland. That’s the dominant species. But also, there are these much smaller climbing grasses, such as Glycine, little climbing plants that weave their way through the grassland; they’re incredibly tiny, even when you’re tending in the cemetery, you don’t necessarily notice them until you peel them back. There are a lot of native moths and butterflies, insect species and native birds as well. There’s also basket grass, which doesn’t really look like a grass – it has broad leaves, and these wavy little feather-like hairs. In the cemetery, as the weather changed and the months got hotter, certain species would begin to take over much more, or they’d shrivel up and die.

The grasslands and herbaceous plants in our cities are so often stripped back or reduced to individual species – but these communities are the foundations of our ecosystems, supporting important insect populations and healthy soils which then support all the other larger species, like birds and lizards etc.

Penny, this is such a lively, engaged project. What was it like supervising?

Penelope Allan: I think the project is extraordinary. What was interesting and significant about Chloe’s project was that she was developing new methods, new methodologies, new techniques, by just immersing herself in the site – to the point of befriending anybody who she came upon.

The beautiful thing about being a landscape architect is the complexity of the projects. Chloe was in the middle of this incredibly complex and vast interplay of a whole lot of different forces. We had a lot of conversations about mowing and Martí Franch’s work and that idea of minimal intervention … but then, she struggled to get hold of the mower, and when she did get in touch with the mower, it turns out there’s a mowing lobby, if you know what I mean?

Big Mowing?

CW: Big mowing, absolutely … that all came from a conversation in the park, when I did the fabric installation, with a man who had spent several years mowing and doing maintenance. He relayed this whole complex dynamic between council and these companies that own the equipment, that have invested millions of dollars into equipment…

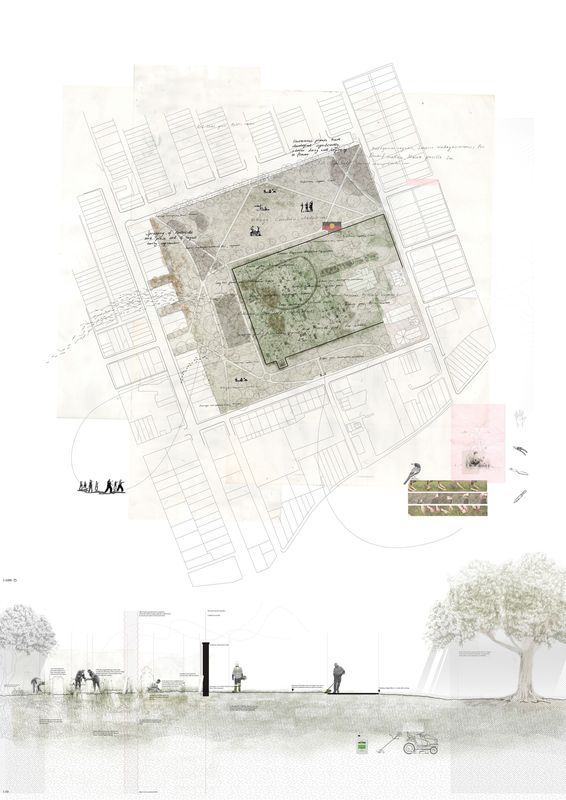

Observations of care, maintenance and species embedded in a site plan and section.

Image: Supplied

PA: It’s not just, “Oh, I know, what needs to be done. I’m a landscape architect.” It’s, “here are all the forces at play. At what point can I intervene as a landscape architect?” I think this is critical to the work that Chloe was doing; she was trying to find that spot, and push. That’s what we’re trying to do at UTS, to push the boundaries of what it means to be a landscape architect and operating in this world, and doing something that’s meaningful and useful. Was there anything you wanted to add about the supervising process, Chloe?

CW: It can be easy to get lost in knowing what parts to include and what parts become a context to the project, and really narrowing that down. Especially when you are so deep in a project, it can be hard to step back and see how other people are seeing it. I think that was really helpful and important – Penny would often say things like, “Okay, but what is it about?”

PA: In our conversations, Chloe would come out with a nugget of gold that she didn’t know was gold. It’s about finding that and refining it.

CW: I think Penny’s encouragement of actually reaching out to so many different people was also really helpful. The amount gained from conversations with different people, different landscape architects, but also different council members – when I could get a hold of them – and experts in different areas and members of the community … that process of reaching out, not keeping it so insular, and expanding it beyond myself was important.

Was there anything else either of you would like to say about the project?

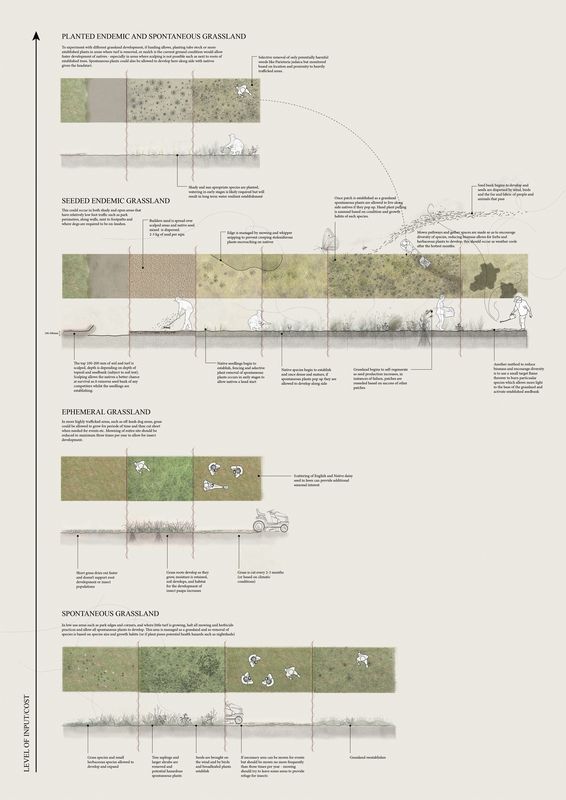

A spectrum of establishment and management based on level of input.

Image: Supplied

PA: It was signifigant that the site where Chloe worked was a cemetery within a park. Because all of the grasslands are being lost, cemeteries operate as a as a kind of refuge, a refugia. Cemeteries and travelling stock routes are practically the only refugia left for grasslands in this region. An interesting question is, because this is happening in the urban environment, what is there in the urban environment that could start to operate as a network of refugia for this diversity? If you imagine the network of city parks having some degree of this kind of management, what would that mean? Is there a way of thinking differently about this kind of space that would offer something to enhance urban biodiversity?

CW: The park itself is this arbitrary boundary; obviously landscape doesn’t adhere to that necessarily. I was often trying to work out, “is this about building and designing a larger network?” I kept it within the boundaries of this one particular site, but I think a part of it was about building this method that could be applied to parks elsewhere, or verges, or people’s backyards, even in my own backyard – so many of the species that I was looking at in the cemetery were popping up in my backyard. More broadly, it’s about creating this approach to management that’s not exclusive to parks.

To view the winners of the 2022 Landscape Student Prize, go here.