The concept of green infrastructure has been gaining ground in Australia over the past few years, with its recognized benefits including a key role in biodiversity protection through the safeguarding and re-establishment of ecological connectivity, the mitigating of air pollution and the urban heat island effect, the provision of recreational opportunities, the augmentation of active transport networks and the elevation of visual amenity. Add to this ever-growing list the boosting of property values and the potential for carbon sequestration, and green infrastructure’s value as a dynamic mix of residential gardens, local parks and housing estates, streetscapes and highway verges, services and communications corridors, waterways and regional recreation areas1 that provides a life-support system for our cities and regions is clear.

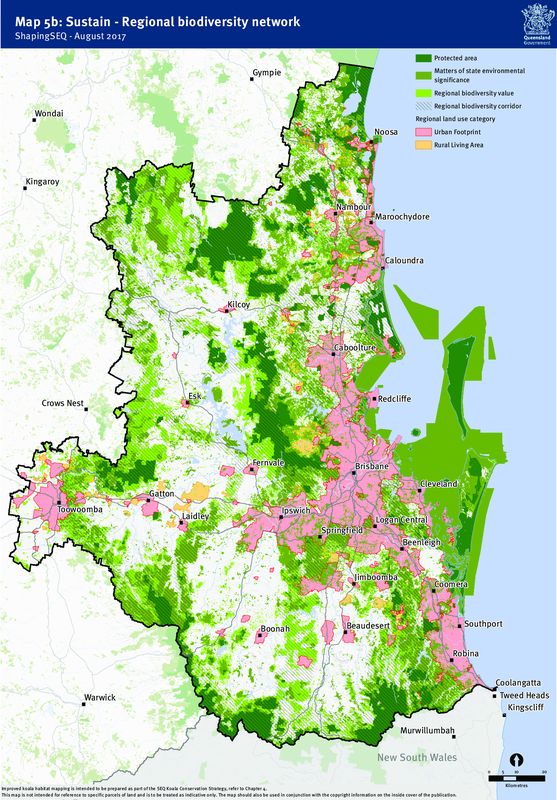

Discussion of green infrastructure has become increasingly common at the level of the street, suburb and city, and many states and local government areas have made much progress in its planning, as evidenced by the abundance of significant plans and policies over the past decade. Some of these include the Perth Biodiversity Project,2 Melbourne’s Urban Forest Strategy,3 the Sydney Green Grid,4 Adelaide’s Green Infrastructure Guidelines5 and the South East Queensland Regional Plan,6 to name but a few. These are bolstered by broader initiatives such as the nationally focused 202020 Vision Plan7 (now Greener Spaces, Better Places).

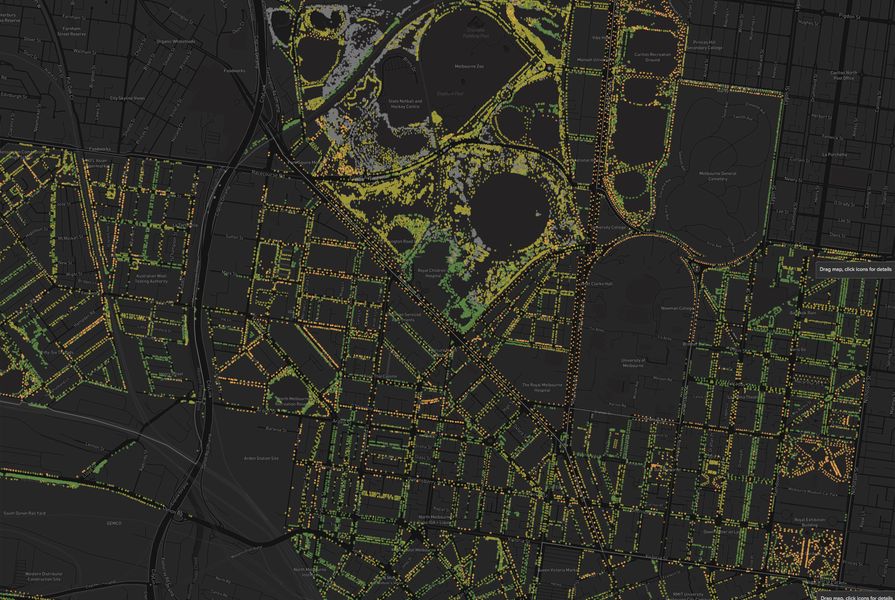

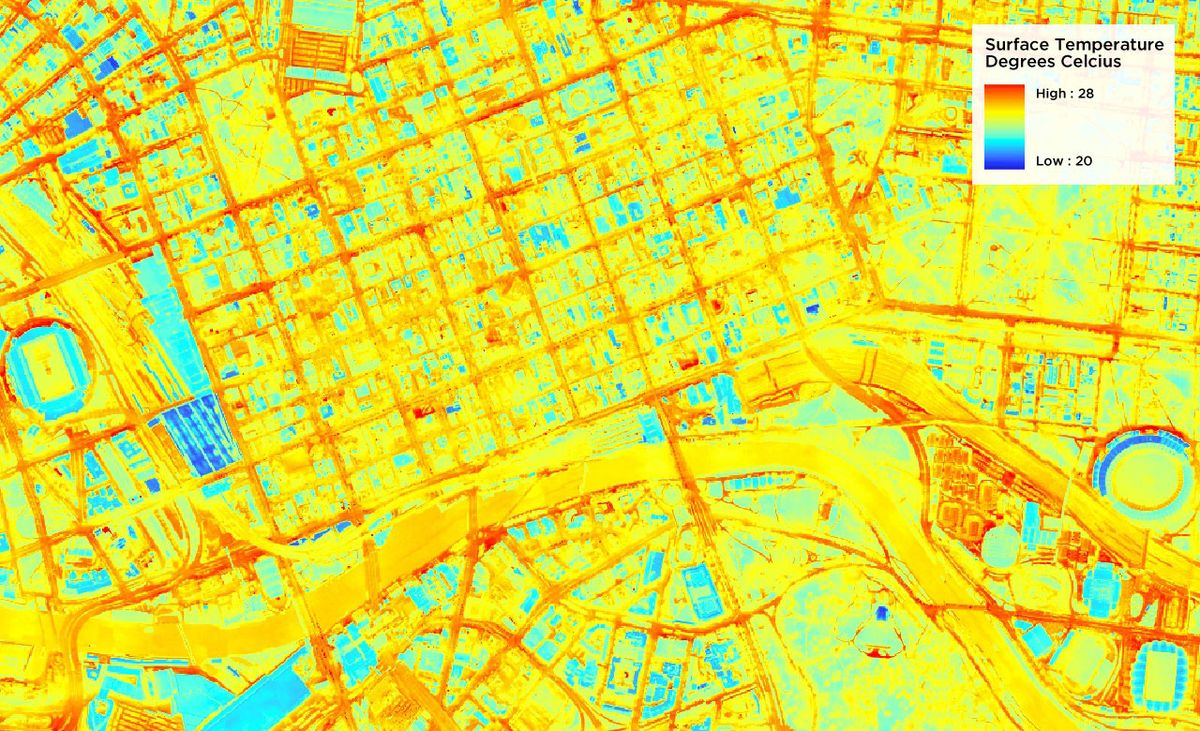

A map showing surface heat in the City of Melbourne during the night.

Image: City of Melbourne.

However, despite some progress, particularly in the development of local-scale rain gardens and street-tree planting across Australia’s cities, the scaling up of green infrastructure into city-wide or regional networks has been very limited; a clear disparity between planning and implementation is evident. Indeed, we have a wicked problem: green infrastructure policies may be effective at small- or local-scale actions (streets and neighbourhood blocks) but they are difficult to scale up. Conversely, overarching regional or metropolitan-scale plans provide arresting and inspiring visions for greener cities, yet seem hard to implement at the smaller scale. So, how might schemes work across scales – from block to city/region – and thereby contribute to the manifold benefits that can be realized from large-scale concerted action, especially addressing the urban heat island and improving ecological connectivity?

Overwhelmingly, the complexity of our urban environments is the roadblock to effective implementation. Our built environments at the local scale are a complex web of public and private lands overseen by an array of different planning authorities. There is a readily observable collision between the intent of green infrastructure and the reality of the complex ground plane: how to physically make space for green infrastructure within busy urban streetscapes? At the scale of the street, difficulties may be compounded by road-safety regulations and the single-minded focus on motor vehicles, along with the whims of individual landholders and the location of grey infrastructure such as water, gas, electricity and telecommunication services. In terms of jurisdiction, there is frequent overlap and siloing of ideas – for instance, main roads and highways are often managed by state government departments and not the local governments through which they pass.

When scaling this up to a suburb, city or region, the project only becomes more complex, especially when we regard the arterial road and rail corridors often favoured by green infrastructure schemes. This complexity is amplified by construction costs and a lack of political will. With an abundance of stakeholders, it also proves difficult to come to any definitive consensus. As these green ribbons move out from local areas, the larger machinations of political forces increasingly come into play.

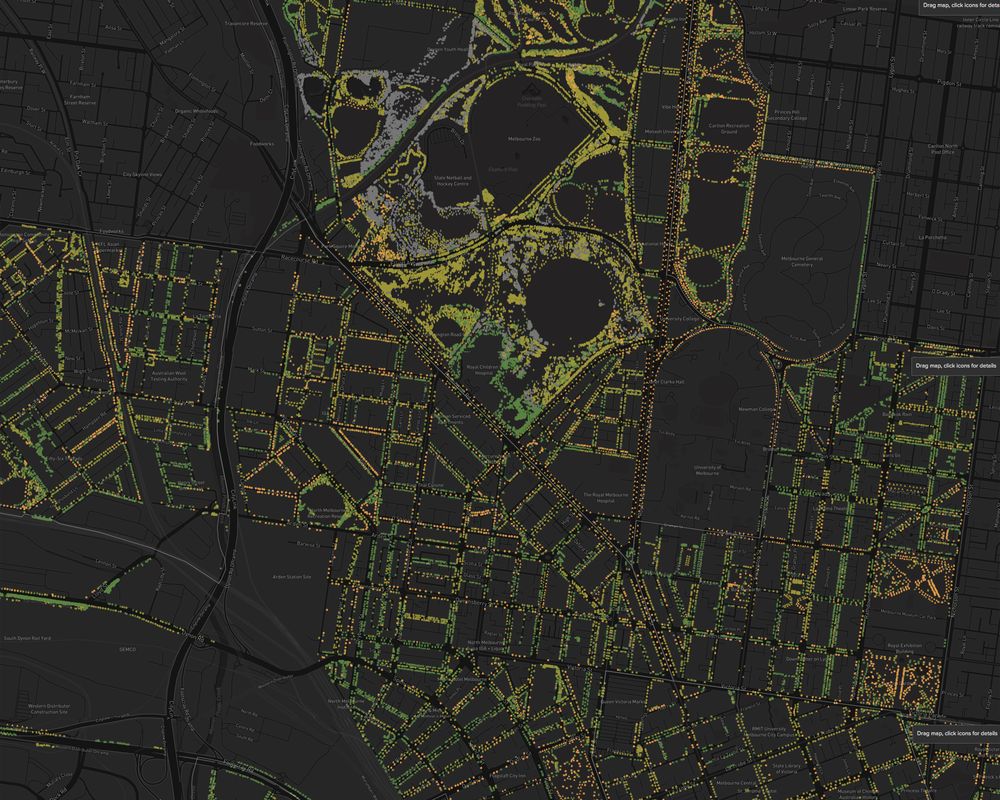

A map showing the regional biodiversity network from the South East Queensland Regional Plan 2017.

Image: Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, Queensland Government.

For progress to be made in meeting green infrastructure’s undeniably exciting vision, we require three actions. First, despite its momentum, green infrastructure is still largely unrecognized as critical infrastructure. The scene-setting has begun but there is still some way to go to offer an all-encompassing reconceptualization of the built environment. In order to frame green infrastructure as a critical infrastructure, with well-documented costs and benefits, the conversation must change. Part marketing pitch, part science, the next step is the further development of an Australian-specific evidence base. Without evidence, the benefits of green infrastructure will be hard to pitch in a world increasingly measured in dollar terms.

Second, landscape architects must continue to play a critical role in the creation and broadcast of plans, imagery and ideas that clearly communicate the capacity of green infrastructure to deliver multiple benefits, energizing governmental policy and grassroots community support. Illustrating and conveying ideas and concepts is a strong point of landscape architecture as a profession. Keep the big green ideas coming.

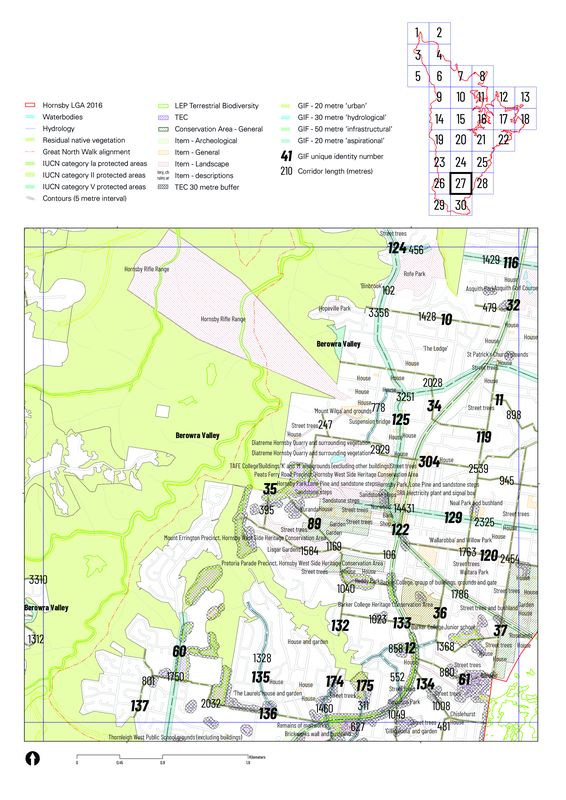

Third, we need a process to refine green infrastructure planning and design. This accuracy needs to be built upon a flexible approach to planning that favours a robust and rational selection of land types that are reasonable candidates for inclusion due to their relative (in)expense and degree of political or citizen support. This “low-hanging fruit” should be where our first actions occur to circumvent as many divisive land-conflict questions as possible. These pilot programs can build the evidence base to support the creation of larger-scale examples. We should consider proposed green infrastructure plans as frameworks only and accept the need for subsequent detailed design stages to ensure a higher degree of testing and resolution through further iterations that allow for a spectrum of design scenarios that explore and quantify design ideas, benefits and cost.8 Where this has happened, some promise is evident, as demonstrated in projects such as Parramatta Ways, developed with Sue Barnsley Design (2017)9 and the Hornsby Shire Council Biodiversity Conservation Management Plan, developed with Rhizome (2020),10 both of which employed mixed methods of stakeholder and community consultation and iterative design to good effect.

Final community and ground-truthed Green Infrastructure Framework in central Hornsby, from the HBMP.

Image: Hornsby Shire Council and Rhizome

Landscape architecture is arguably the profession best placed to foreground the holistic and inclusive approach required for planning of this type; to conceptualize our cities, their biodiversity and their citizens as evolving and ever-changing systems, to work across scales, to bring together disciplines, community and stakeholders with a common vision is our core business, is it not? On the coat-tails of the COVID-19 pandemic, interest in parks and open space – both from the general public and in the political realm – has spiked. This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for landscape architecture to really lead, to go beyond useful but superficial diagrams and to instead provide a lasting legacy for our cities. Without further collective action, we will continue to produce green squiggles that risk remaining just that – lines on a map – losing the potential for generative conversations around what kinds of cities we want to live in in 5, 10, 25 and 100 years time.

1. Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, “Adapting to Climate Change: Green infrastructure,” 2009, aila.org.au/documents/AILA/Advocacy/National%20Policy%20Statements/AILA%20Green%20Infrastructure.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

2. Australian Institute of Landscape Architects, “Adapting to Climate Change: Green infrastructure,” 2009.

3. City of Melbourne, “Urban Forest Strategy: Making a great city greener 2012–2032,” 2012, melbourne.vic.gov.au/sitecollectiondocuments/urban-forest-strategy.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

4. Government Architect NSW, “Sydney Green Grid,” 2017, governmentarchitect.nsw.gov.au/projects/sydney-green-grid (accessed 11 December 2020); NSW Government Architect’s Office, “The Green Grid: Creating Sydney’s Open Space Network,” 202020vision.com.au/media/7200/barbara-schaffer-gao-sydneys-green-grid.pdf (accessed 15 December 2020).

5. City of Adelaide, “Adelaide Design Manual: Green Infrastructure Guidelines,” 2016, adelaidedesignmanual.com.au/design-toolkit/greening (accessed 11 December 2020).

6. Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, “Shpaing SEQ: South East Queensland Regional Plan 2017,” dilgpprd.blob.core.windows.net/general/shapingseq.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

7. Jess Miller and Ben Peacock (eds), “The 202020 Vision Plan,” 2015, 202020vision.com.au/media/41955/202020visionplan.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

8. Simon Kilbane, Richard Weller and Richard Hobbs, “Beyond ecological modelling: ground-truthing connectivity conservation networks through a design charrette in Western Australia,” Landscape and Urban Planning, vol 191, November 2019, 103–122, dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.05.001 (accessed 15 December 2020)

9. City of Parramatta, “Parramatta Ways: Implementing Sydney’s Green Grid,” 2017, cityofparramatta.nsw.gov.au/sites/council/files/inline-files/Parramatta%20Ways%20Report_0.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

10. Hornsby Shire Council, “Your Vision, Your Future: Sustainable Hornsby 2040 – Draft,” 2020, future.hornsby.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/draft-Sustainable-Hornsby-2040-Strategy.pdf (accessed 11 December 2020).

Source

Practice

Published online: 9 Apr 2021

Words:

Simon Kilbane

Images:

City of Melbourne.,

Department of Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning, Queensland Government.,

Greener Spaces, Better Places.,

Hornsby Shire Council and Rhizome,

Oom Creative

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2021