Openwork is a landscape architecture practice that has evolved by moving beyond convention. Founding member Mark Jacques frames the studio’s approach as a conscious destabilization of a project’s agreed or orthodox scope. “By deploying an oppositional argument early on in the design process, we try to put a project outside of an expected condition,” he says. It is these acts of subversion that are hinted at in the practice’s name; by pushing the limits of a project’s scope, the studio opens up new and unexpected possibilities.

Founded in Melbourne in 2016, Openwork is fast becoming known for its portfolio of small-footprint public projects that generate effects not through imposition but through inversion. “RMIT gave us an income, so there was an opportunity to jump off and take a risk,” reflects Jacques on the studio’s beginnings. That risk – and the ensuing business model upon which the practice is based – is founded in making decisions that aim to keep the studio happy in its work. “The problem of practice – with any practice – is being asked to do something in the first place,” Jacques explains. “In our view, the request to do work is almost always a disappointment.”

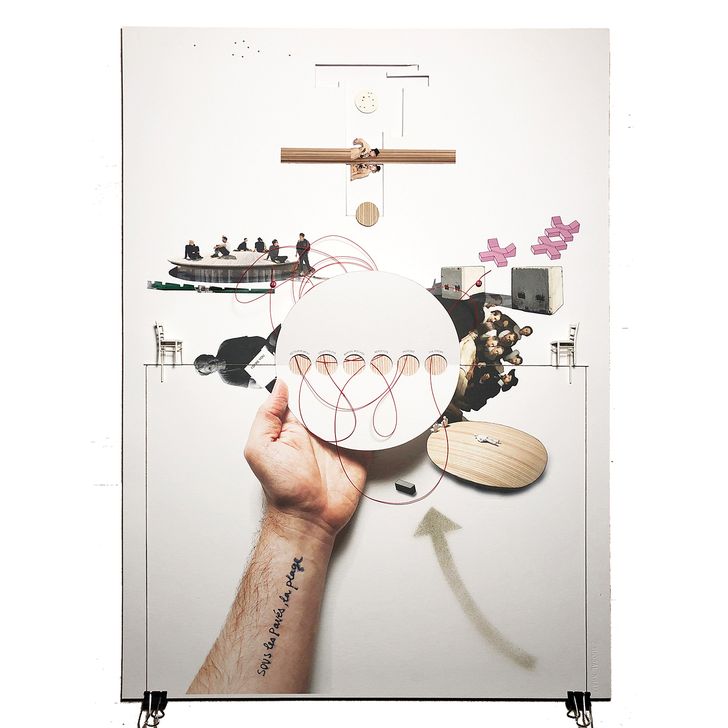

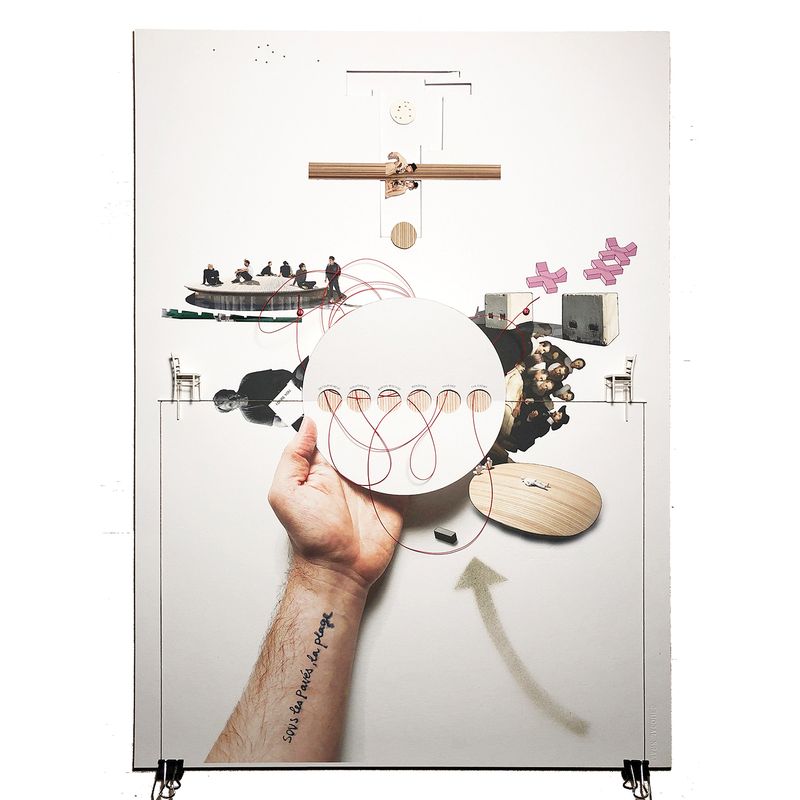

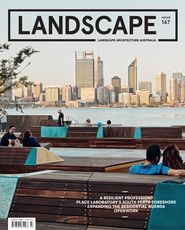

An ideogram for Openwork’s bollard seating at RMIT Design Hub.

Image: Openwork

At Openwork, design is reframed as a response to this problem of practice. “Our work is often animated against the disappointment of a brief,” says Jacques. “Faced with any brief, the question becomes, what can we do to give ourselves agency to do the things we want to do – and spend our time how we want to spend it?”

“We talk a lot about projects having a ‘meta-brief,’” adds Ben Kronenberg, another of the Openwork team. “This could be the chance to work with someone that we’ve never worked with before, or the chance to test something we want to test – an idea or a methodology.”

A recent example is Nightingale Village – a residential development of seven apartment buildings designed by six local architecture practices in Melbourne’s inner-north. While the built outcome of Openwork’s involvement features rooftop gardens, for the practice, the project was not about gardens exactly, but about the opportunity to “explore this idea of shared infrastructure and where that could go.”

This proactive reframing of project briefs goes to the heart of the Openwork ethos. “Rather than waiting to see what’s out there, we try to think, “How can we drive the conversation through what we want to do?’” says Kronenberg.

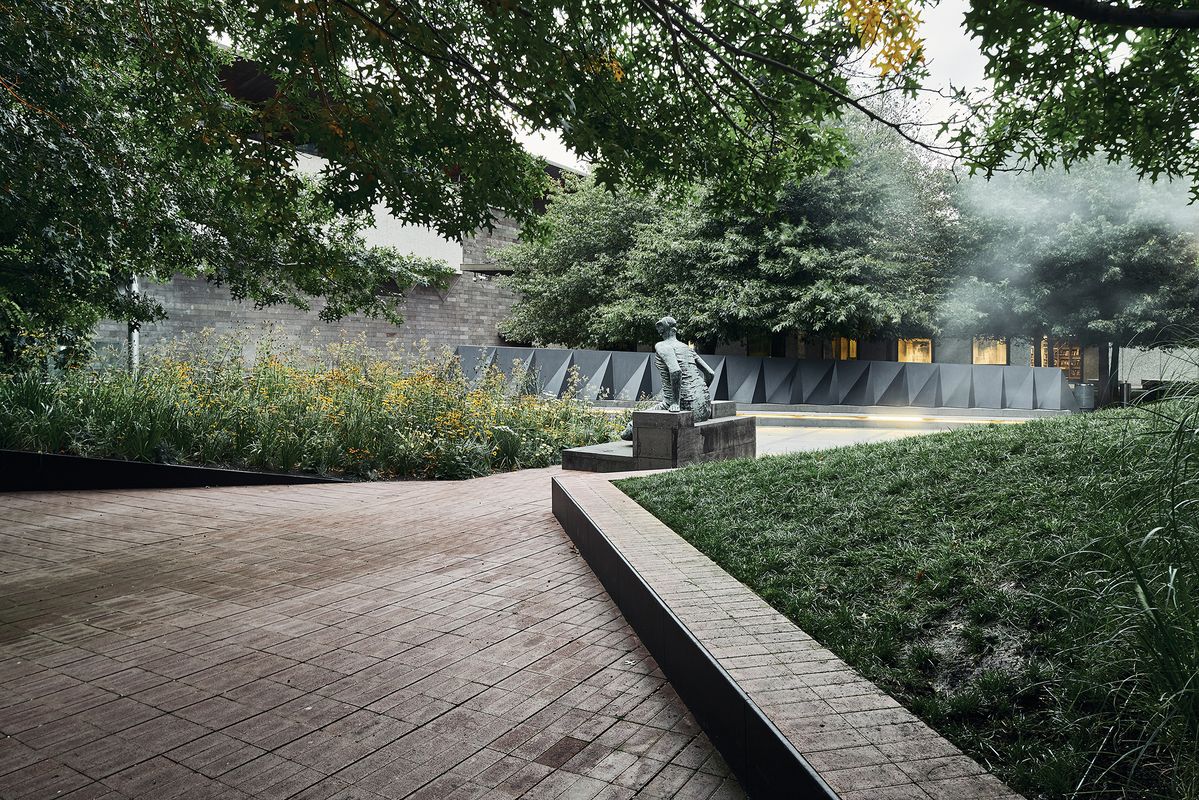

The landscape at Parks Victoria’s new Albert Park office by Openwork with Silk Consulting Landscape Architects positions the building as a host for recolonization by the site’s pre-European ecology.

Image: Peter Bennetts

One avenue has been the university system. Within the studio’s nine to five, teaching has been embraced as a core practice. A series of design studios run at RMIT University’s School of Architecture and Urban Design, including one with regular collaborator architect Amy Muir, functions as a vehicle for collective research and speculation.

The future that Openwork is concerned with is tied strongly to the public realm. “What connects our projects isn’t an advocacy for the disciplines of landscape architecture and urban design per se, but how the tactics of those disciplines can enable a public realm,” says Jacques. Rather than grand impositions of a landscape architectural authorial voice on a place, Openwork finds a rupture or tipping point within a site’s existing condition that enables a different understanding and behaviour.

Doubleground, the 2019 NGV Architecture Commission designed with Muir, for instance, was, in Jacques words, “largely about occasioning these big tectonic shifts that transformed the garden from its benign and weirdly municipal condition into something else.” The same conceptually layered approach is evident in the practice’s bollard seating at the Sean Godsell Architects-designed RMIT Design Hub, where a “copy of a copy” of the building’s distinctive louvres guards against traffic, while humorously critiquing the building’s legacy.

Bollard seating at the Sean Godsell Architects-designed RMIT Design Hub mimics the building’s distinctive louvres.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The 2019 NGV Architecture Commission, Doubleground, by Muir and Openwork.

Image: Peter Bennetts

At one of Openwork’s most recent projects – Parks Victoria’s new Albert Park office undertaken with Silk Consulting Landscape Architects – the building, by Archier with Harrison and White, has been positioned as a kind of ready-made host, with surfaces ripe for recolonization by the site’s pre-European ecology. This response is continued – with a twist – at Monash University’s Chancellery building, where the team worked with AKAS Landscape Architecture to develop a concept for the landscape that teases out the Clayton campus’s historic narrative of indigenous planting.

From its beginnings, the Openwork team has always been small – “around six seems to be the magic number” – and this continues to be a deliberate choice. Maintaining a collective culture, where everyone can work across all projects, has been one key reason; wanting to minimize the need to take on work that might not necessarily fit with the practice’s principles has been another.

“Part of being small, though, means we don’t have the grunt of a bigger practice,” Kronenberg says. “So when it comes to larger projects, we engage and collaborate with other practitioners, specialists and experts.” A conscious decision in setting up the studio was to operate not as a one-stop shop, Jacques adds, “but like a team in a heist movie, where particular skills are brought together to do a particular job, then disperse and perhaps never work together again!”

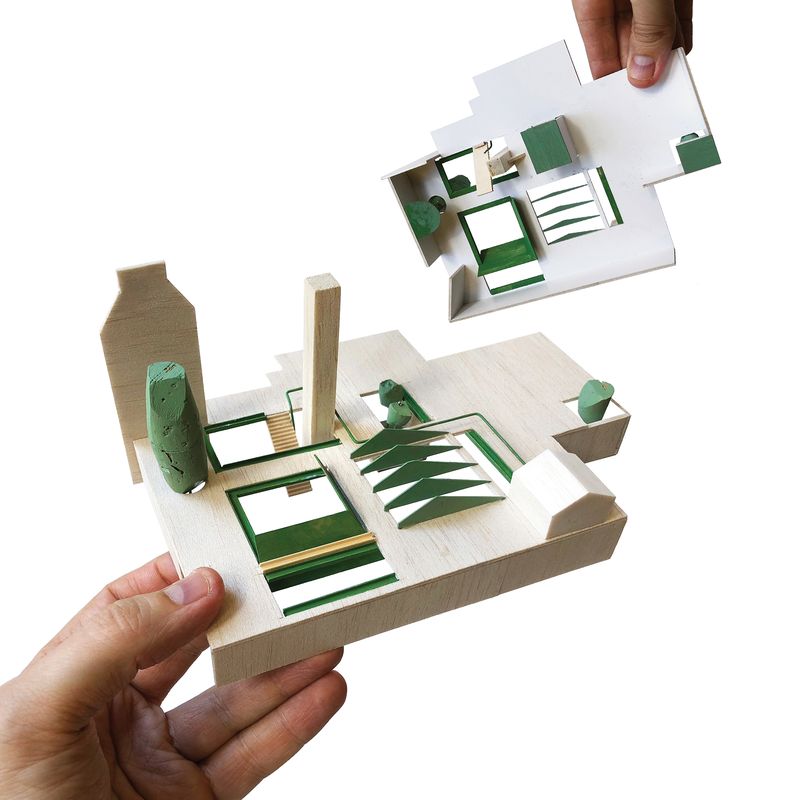

Openwork’s light-filled studio space in central Melbourne’s Elizabeth Street is littered with models – a three-dimensional cityscape of thinking in motion. Why craft models in an age of digital representation? For the studio, model-making time is slow time – time for contemplation. “There are certain things, whether its measuring pieces of timber or waiting for the paint or glue to dry, where your conscious brain is occupied, but the reflective part of your brain seems free to wander,” says Jacques. But beyond their important role in the studio’s design development, models, Jacques believes, have their own unique power. “I still think there’s an enduring faith in beautiful objects as ways of advocating for ideas.”

Concept models for a beer garden.

Image: Openwork

With such a reflective and considered practice, it’s no surprise that Openwork’s portfolio is rapidly expanding – public realm works including the Victorian Family Violence Memorial (through the City of Melbourne and with Muir) and the Royal Tasmanian Botanical Gardens visitor centre (with Taylor and Hinds Architects) are among many currently on the drawing board. Yet, despite the studio’s rising profile, Jacques remains modest: “There’s nothing revolutionary about the practice. It’s a simple shift on the orthodoxy of an office, but one that tries to increase our happiness in doing our work.” Reflecting on the practice as a conscious collective, he continues: “For us, the work of design is always more interesting than the authors of that work. We’re interested in the work and the ideas. As soon as anyone tries to put an authorial voice on, that begins to get warped.”

Openwork is Benjamin Kronenberg, Dylan Gilmore, Elizabeth Herbert, Marijke Davey and Mark Jacques.

Source

Practice

Published online: 23 Nov 2020

Words:

Emily Wong

Images:

Openwork,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2020