Gondwana Link is a landscape restoration project that protects and reconnects habitat across 1,000 kilometres in Western Australia’s south-west. This region, classified as a global biodiversity hotspot, is home to an ancient ecology with more than 7,200 vascular plant species, 80 percent of them endemic.1 While rich in biodiversity, the area has suffered the drastic impacts of land clearing for agriculture, with only 30 percent of primary native vegetation remaining.2

In this context of opportunity and of loss, Gondwana Link offers an approach to broad-scale repair. While conventional techniques focus on the regeneration of isolated remnant patches, this project provides a framework for social and ecological restoration at a landscape scale: a statewide corridor that crosses boundaries and bioregions.

The complex and wide-ranging networks spanning these landscapes are drawn together by Gondwana Link’s shared vision for landholder-led conservation and restoration – an aim to reconnect country across south-western Australia. The connection runs from the south-west forests at the coast to the Greater Western Woodlands at the border of the Nullarbor Plain, through a central region that spans Walpole Wilderness Area and across the Fitz-Stirling region, named for the Koi Kyeunu-ruff (Stirling Ranges) and Fitzgerald River national parks.

Since its initiation by CEO Keith Bradby in 2002, the organization has been working with partners to build and reconnect fragmented bushland habitat. “Gondwana Link came about over a long period of time,” says Bradby. “While the land care movement was doing great stuff, we were at risk of suffering a death by a thousand projects. We really needed to step up in scale.”

“We started by doing. It’s pretty simple stuff, really – ‘Here are the big bits of bush, here are the bits in between. Let’s start by buying some properties in those gaps and getting them back to bush. Our initial move was to build momentum, build local support and grow organically. Twenty years later, we’re still using this approach.”

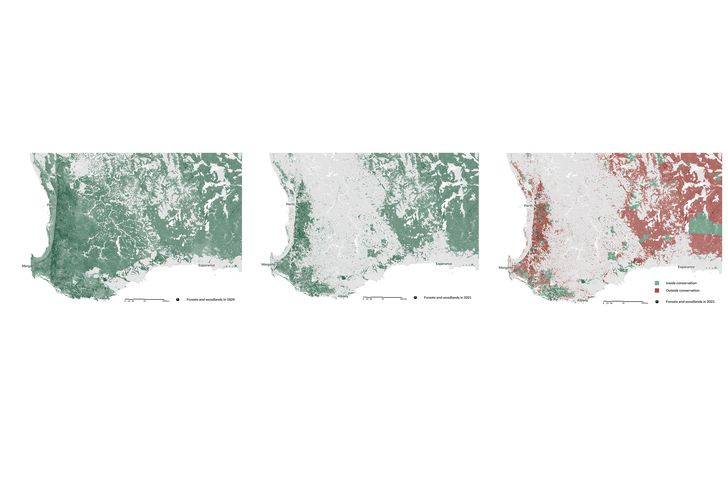

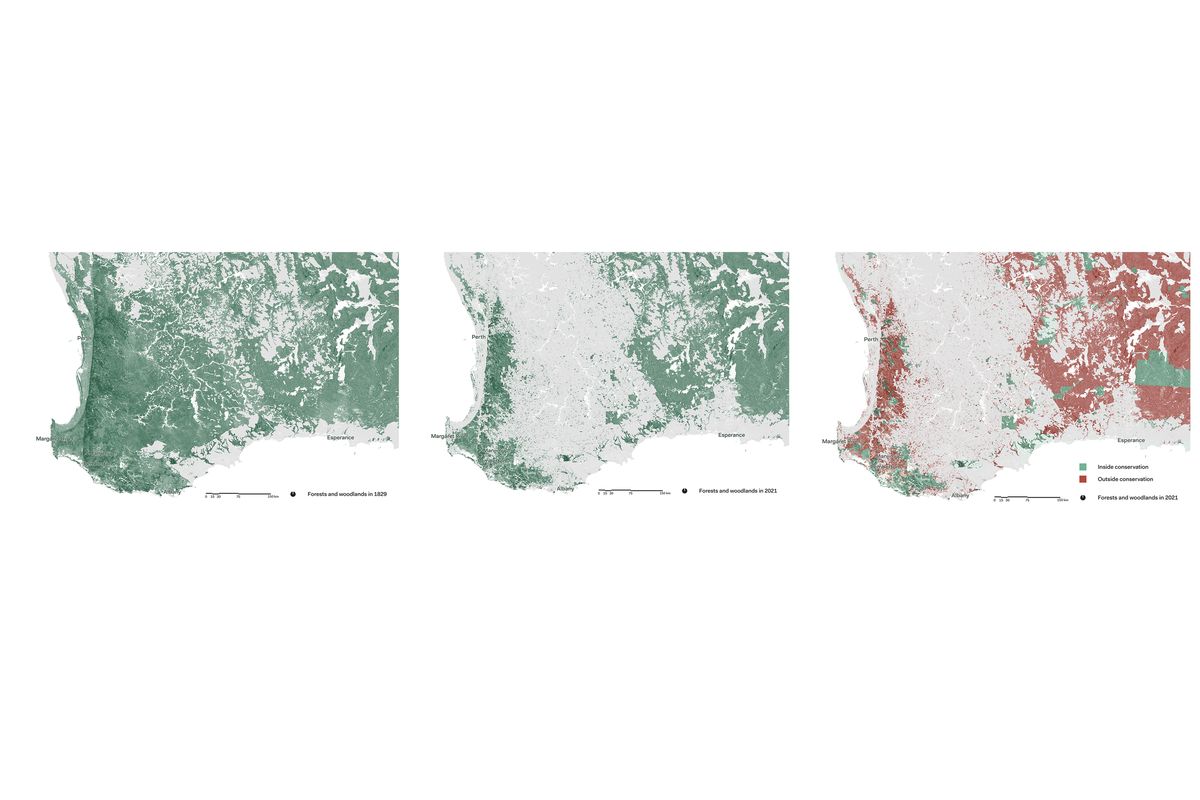

The clearing of native vegetation for agriculture has had a drastic impact on the landscape of south-west Australia over the past 200 years. Much of the remaining vegetation is unprotected.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin

Collaboration and the support of local efforts are central to the Gondwana Link way of working. While the organization’s partners are drawn together by the collective vision of the Link, they are also bound by their shared values. In Bradby’s words, the organization works with those who have their “eyes wide open … We deal with people who can see what’s happening in the landscape, and have values beyond their immediate self-interest. They feel for Country. A lot of people with ‘eyes wide open’ feel genuine pain when they look at what’s happened. It’s really good for their wellbeing and mental health to do something about it.”

With the Link spanning multiple languages and cultures, the organization partners with multiple First Nations groups. Other collaborators take the form of local, regional, national and international groups; local government and state government authorities; and private landholders. “The diversity of groups, individuals and mechanisms that we use to deliver and fund projects matches the diversity of landscapes that we work across. This is a pivotal strength of the Link,” says Bradby.

In developing restoration projects alongside partners and with the support of primarily private funding, the role of Gondwana Link is then to support existing work on the ground.

The impact of a collaboration with private landholders and community groups who have longstanding connections to place can be seen in the Ranges Link project, one of the earliest initiatives of Gondwana Link. In the early 2000s, a significant gap was identified in the Kalgan River valley, a productive farming area on Menang Noongar and Goreng Noongar Country in the Fitz-Stirling region.

“What we’re trying to undo is the incredibly careless expansion of agriculture [that occurred in the south-west] in the 1950s and ’60s,” explains Bradby. “Most of Western Australia’s southern country was not farmed until then. During those decades, any bit of the landscape that you could drag a plough over was carved up. While we’ve annihilated most of the Wheatbelt, we’ve got some hills left in [the central region] – big blocks of habitat to build from.”

The aim of the Ranges Link was to connect two of these “building blocks.” Borong-gorup (Porongurup National Park) and Koi Kyeunu-ruff (Stirling Ranges National Park) had become two isolated islands of biodiversity within a sea of agricultural land. This is a common condition in areas within the Link – private property often holds precious, but disconnected, remnant bushland, with the biodiversity in these areas under threat because of their isolation.

With the assistance of Gondwana Link and other partners, a Ranges Link Conservation Action Plan (CAP) was formulated by the Oyster Harbour Catchment Group, a local landcare organization. The CAP was focused on making connections between the national parks, through agricultural land.

“[The local community] saw what Gondwana Link was achieving in the Fitz-Stirling region at the time, and they thought, ‘We want some of that too.’ It was almost as if Gondwana Link getting on and doing things at a bigger scale unleashed the local imagination a bit,” says Bradby. “We got the [local groups] involved in the Conservation Action Planning process, which was about meshing our ideas together but also about lifting the thinking from ‘What are the little bits we can do?’ to ‘How can we make strategic change?’”

Nowanup rangers planting seeds as part of the Gondwana Link ecocultural project.

Image: Amanda Keesing

Key to the success of the Ranges Link was coordination across two privately owned properties – Caladenia Hill and Twin Peaks Reserve. Caladenia Hill is a formerly agricultural property that was purchased in 1984 by Peter Luscombe, a local native plant specialist, ecological restoration pioneer and farmer. Under Luscombe’s care, the property has been revegetated and regenerated, with biodiversity rebounding and fauna returning. In the early 2000s, a nearby land parcel was purchased by the Friends of the Porongurups and became the Twin Peaks Reserve. Caladenia Hill shared a common boundary with this newly protected reserve, and together, these two properties now form a connected land area of more than 1,000 hectares.

The broader vision of Gondwana Link provided a framework for connecting these remnant areas to a broader social and ecological network, while respectfully building on years of grassroots landscape restoration work. The connected areas of Caladenia Hill and Twin Peaks Reserve now form a key stepping stone in the Ranges Link.

As well as supporting the extraordinary efforts and achievements of community groups and private landholders, Gondwana Link works together with First Nations groups, connecting into tens of thousands of years of knowledge of caring for and management of Country. Gondwana Link also attracts and supports ongoing partnerships with larger organizations, including the independent environmental enterprise Greening Australia, which owns three properties within the Link.

At Nowanup, a 750-hectare lot on Goreng Noongar Country, Greening Australia and Gondwana Link work together with the Noongar community to regenerate and heal Country. The property is key to the connection between Koi Kyeunu-ruff (Stirling Ranges National Park) and Fitzgerald River National Park.

After the property was secured in 2004 via the National Trust’s Bush Bank fund, a group of Noongar Elders was invited to manage and care for the land. Greening Australia later assumed formal ownership, with the property now being managed by Noongar people, as Noongar Boodjar (Noongar Country), under the leadership of Elder Eugene Eades.

“When we first came out to Nowanup, we had a look around and we had a feeling we could have some strong connections to this Country – it was Noongar Boodjar,” says Eades. “On our way out of the gate, Keith Bradby said, ‘This is Noongar Country. The gates are open, do what you need to do to make things better for your people.’

“Then, the Elders appointed me as a cultural advisor. My role is to be in-between the Elders and the families that have connection to Country; following Noongar protocols with Noongar people and bringing people back so they can have a say in how the restoration process takes place.”

Tractor lines mark out the 200-metre-tall kangaroo design, where plants are now beginning to grow.

Image: Peter Banyard

The large-scale planted representations of the kangaroo, the malleefowl and the goanna are based on designs by Errol Eades.

Image: Peter Banyard

Nowanup is a site of landscape regeneration, as well as a place of cultural education. After almost 50 percent of the property was cleared for agriculture during the 1970s, the land is now being regenerated in a shared process of two-way knowledge-sharing between Greening Australia and Noongar people. “We do restoration in partnership so we can learn together to heal the land,” says Eades.

As part of the regeneration process, stories have been embedded into the landscape – art in the form of large-scale endemic plantings. “We saw that there was some cleared land on the property,” says Eades. “The old people said, ‘Eugene, put back that totem that belonged to that Noongar mob that lived here a long time ago, and do it big enough so that the whole world can see it from the sky.’”

These totems are represented as a goanna, a malleefowl and a kangaroo, in forms designed by Eugene Eades’s nephew, artist and ranger Errol Eades. Eugene Eades advised on species selection, and Nowanup rangers worked together with Greening Australia on planting and regeneration work.

Paths weave through the cultural landscapes at Nowanup – walking trails where stories can be told and knowledge can be handed down. A significant meeting place has been built, and camps for young Noongar people are held at the property. Curtin University also uses it as a bush campus for on-Country trips and cultural learning units.

Social and ecological networks are being strengthened hand-in-hand at Nowanup, as they are in each project within the broader Link. Gondwana Link has connected with the people who have longstanding relationships with each place, and facilitated relationships with funding bodies and larger organizations. Here, the reciprocal value of two-way learning becomes clear.

Healthy country depends on good relationships – and these relationships take time. Gondwana Link demonstrates the potency of a stable, long-term strategy that is flexible enough to support the people who are on the ground, doing the work – those who know their places best.

It can be challenging to remain connected to the broader impact of community and individual efforts. The power of Gondwana Link’s approach is in connecting local heroes to a broader strategy, to facilitate collective action on multiple levels. In sharing about Nowanup, Eades reminds us that “as we heal the land, the land will heal us.” In a world full of dismal environmental news, Gondwana Link has continually made positive impacts, grasping the best opportunities we have to regain interconnected social and ecological function, at scale.

1. Hans Lambers and Don Bradshaw, “Australia’s south west: A hotspot for wildlife and plants that deserves World Heritage status,” 18 February 2016, The Conversation, theconversation.com/australias-south-west-a-hotspot-for-wildlife-and-plants-that-deserves-world-heritage-status-54885 (accessed 17 May 2022).

2. Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/southwest-australia (accessed 17 May 2022).

Source

Practice

Published online: 16 Sep 2022

Words:

Rosie Halsmith

Images:

Amanda Keesing,

Daniel Jan Martin,

Greening Australia,

Peter Banyard

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022