Humanity faces an urgent challenge to redesign our communities, including buildings, neighbourhoods, parks and infrastructure, to mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts. How can we develop novel responses situated within the here and now, that anticipate and reinforce viable mid-term and long-term strategic outcomes?

Two projects I have worked on recently might provide some insight. The first was developed through Yale University’s Urban Ecology and Design Laboratory (UEDLAB), working with my former PhD student Timothy Terway as part of the Southeastern Connecticut Regional Framework for Coastal Resilience. The Nature Conservancy was the client and the project worked across towns in Connecticut, including Stratford. The second example is the Design with Country studio which I co-taught in 2021 with Jefa Greenaway (Wailwan/Kamilaroi) and

Kirstine Wallis (Palawa), two Indigenous staff at the University of Melbourne. Both these examples, in which long-term landscape vision around climate adaptation informed near-term design proposals, could encourage and inspire Australian landscape architects. These approaches can also build on Indigenous perspectives that foreground generational thinking. In both instances, the use of temporal diagrams in planning and communicating to decision-makers supported a deeper appreciation of the project intentions and the value of near-term actions that lead to long term benefit. The approach also highlights ways of avoiding mistakes that could reduce long-term adaptability.

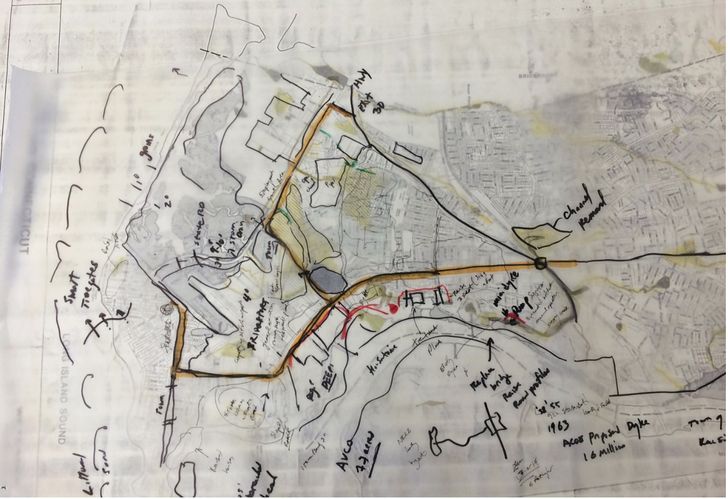

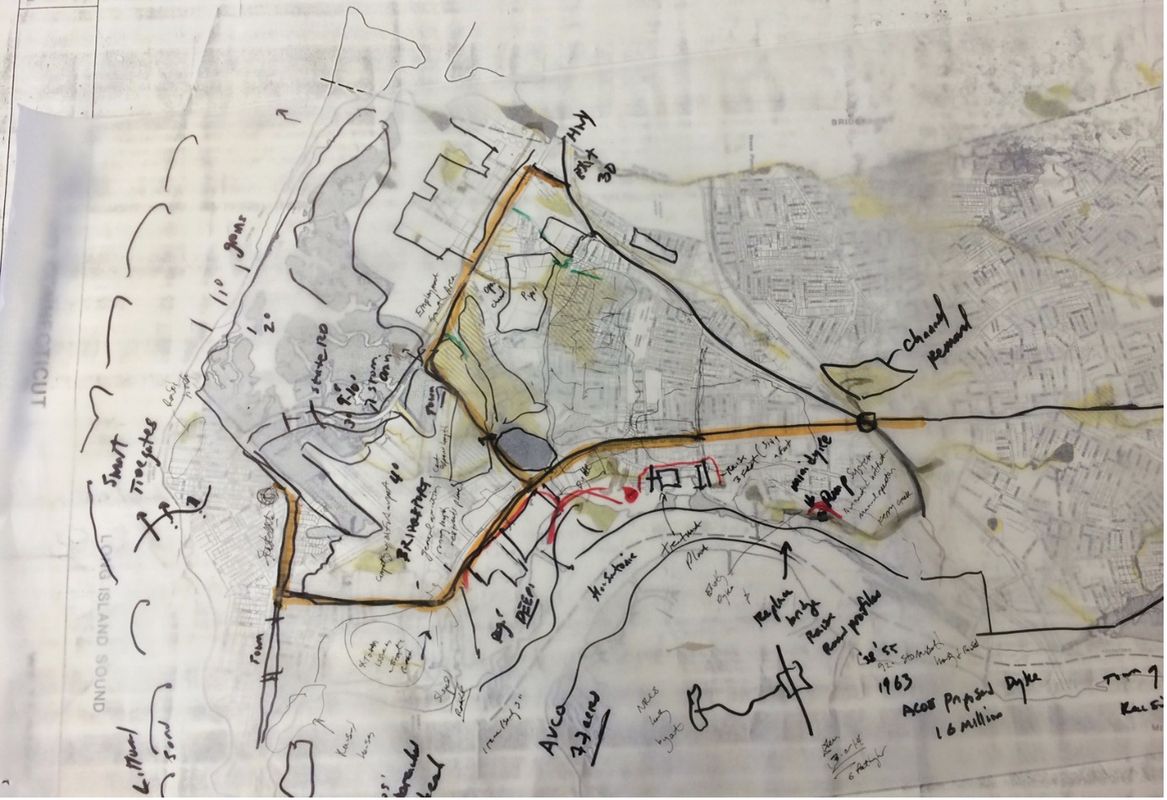

Alexander Felson, Timothy Terway and Adam Whelchel of The Nature Conservancy met with John Casey, the Stratford town engineer, to work through project challenges and identify locations where adaptations had occurred or were needed.

Image: Alexander Felson

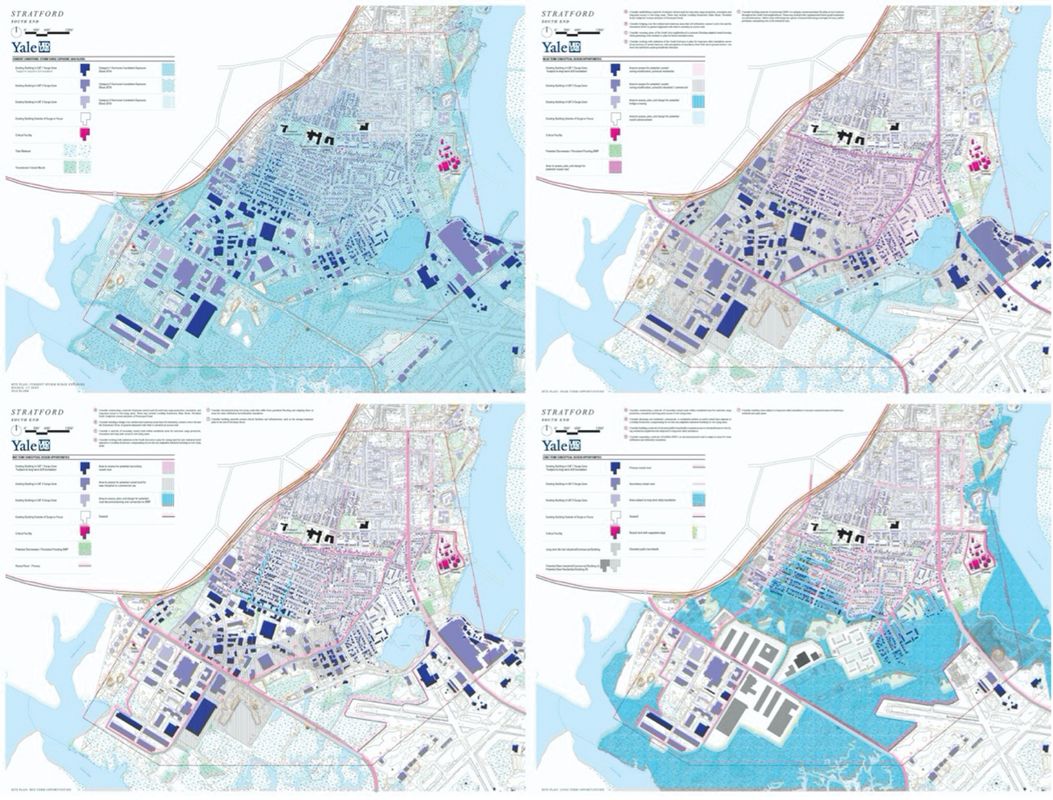

The project in Connecticut provides an example of how near-, mid- and long-term planning strategies can shift our assumptions about actions and their consequences and can recalibrate the value of unconventional solutions that may prove to be more resilient in the long-term. At Stratford, a town founded in 1639, and originally named Cupheag, meaning “a place of shelter” in the Native American Paugussett language, a long industrial history had created land use “knots” consisting of complicated overlapping contaminated sites and conflicting land uses. Stratford is home to Sikorsky, which has built helicopters there since 1929, and it once hosted the Stratford Army Engine Plant and Raymark Industries. This industrial past has left Stratford with challenging post-industrial sites in the floodplain that remain problematic and politically charged, including two US Environmental Protection Agency Superfund sites.

Parts of Stratford represent the kinds of complicated land use challenges one finds in urbanized floodplains across the world. Sikorsky Memorial Airport was built on a large wetland complex that supported abundant species and habitats; the town developed an industrial area along the north side of the wetland complex; and a state highway and rail corridor were built parallel to the coast that further reinforced the industrial zone. There are no other locations across Stratford to accommodate this kind of land use and it was recently designated an Employment Growth District. Further complicating the situation, the Lordship waterfront neighbourhood is located on an island of higher ground past the airport. This puts additional demands on maintaining road access, including a lengthy road that traverses the wetland complex. It also means that there is investment in the homes on the island creating additional interest in preservation. An additional challenge is that Bridgeport, the adjacent town, owns the airport, creating a displaced ownership situation that resulted in various interests being misaligned.

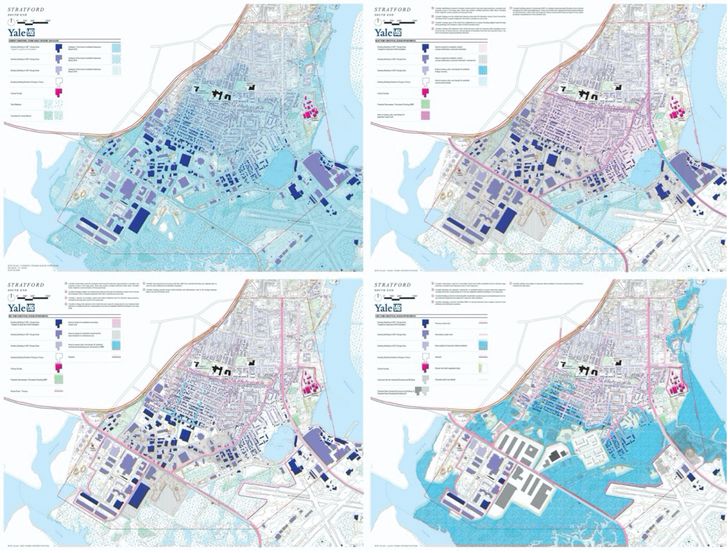

The 2016 Town of Stratford Coastal Community Resilience Plan proposed flood walls along the entire perimeter of the Employment Growth District and industrial zone, with pumps on the interior that would function continuously to remove the water. Our project presents an alternative approach that prioritizes the rehabilitation of the wetland complex and facilitates transitional neighbourhoods and island industry plots with strategic retreat to allow for flooding while maintaining some functionality of the industry and Employment Growth District in the face of climate change. We allow for water to reconnect across the two now-disconnected wetlands in Stratford, using the existing tidal Frash Pond in the South End neighbourhood as part of the integrated wetland complex and retreating in a few selected areas that are particularly vulnerable. We promote certain roads as resilience corridors with raised properties that can accommodate flooding and reconstructed viable wetland habitats as part of the design. Near-term investment strategies are often focused on problem solving or building to preserve what exists today, instead of exploring long-term futures to inform smart near-term investments that anticipate future flooding. Our approach, rather than producing a large-scale flood defence system that will require constant pumping to maintain, proposes a different vision for the future where flooding is incorporated into industry and neighbourhood. The project highlights that adaptation opportunities often require working across zones that may include multiple properties and housing clusters alongside industrial zones and roadways, where individual homeowners or businesses are not the ideal decision-making scale.

The example illustrates how land use history and urbanization, alongside ownership patterns and town priorities, can complicate adaptation options for the town inhabitants and for the health of ecological systems. Landscape architects, working on sites like these, must consider the geography and ecology alongside communities and the built environment to envision holistic adaptation strategies.

Final drawings were prepared as part of the Southeastern Connecticut Regional Framework for Coastal Resilience and shared with the town for discussion. The concepts were developed by Alexander Felson and Timothy Terway of the UEDLAB and drawn by Timothy Terway.

Great Birrarung Parkland: Design with Country studio

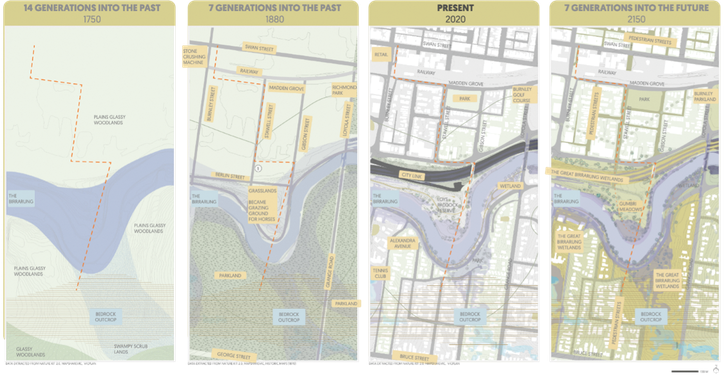

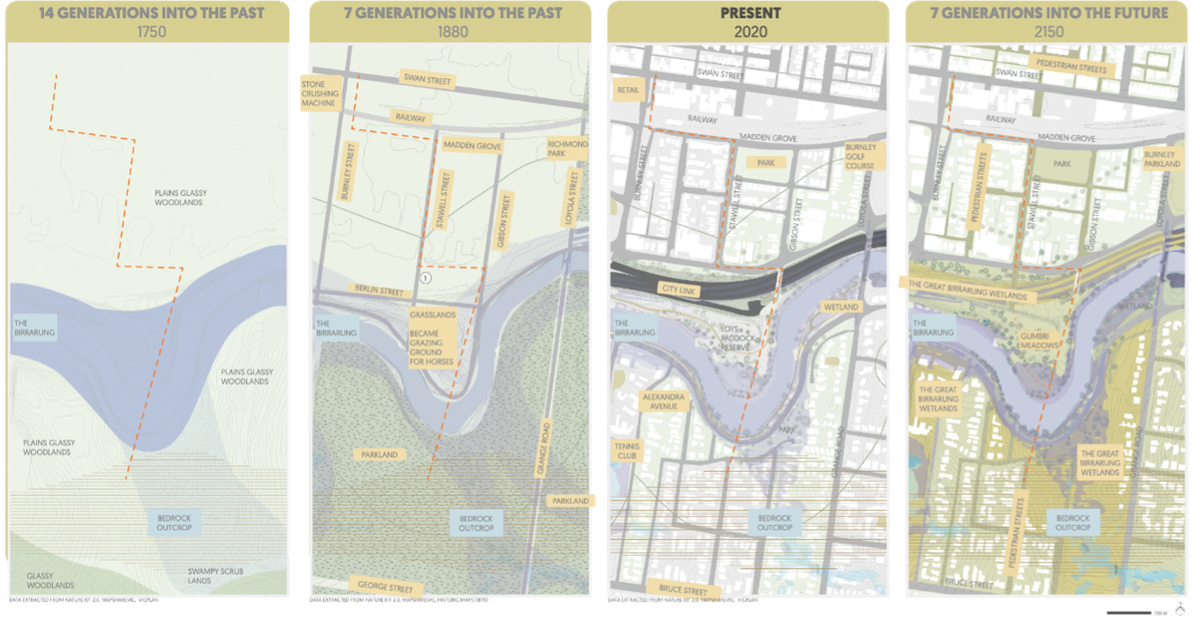

The second example includes student work as part of the Designing with Country: Resilience Studio at the University of Melbourne, an interdisciplinary course working across landscape architecture, urban design, and architecture that focused on the Birrarung (Yarra River). Through cultural immersion, students navigated the concept of connection to Country, engaging in deep listening and group exercises and focusing on Aboriginal heritage and history of Country in relation to landscape architecture. Students specifically explored the concept of the Great Birrarung Parklands in response to the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birrarung murron) Act 2017, which established the Birrarung Council. The Act builds on the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung people’s recognition of the Birrarung as one living and integrated natural entity. Students explored perspectives of Country and custodianship, working with the concept of bi-cultural environmental net gain, which incorporates Traditional Owner and community aspirations. Students started the course by creating their own interpretation of the Birrarung as a living entity.

The work studied the past, present and future conditions of multiple sites along the Birrarung in the City of Stonnington and City of Yarra. The past geology and land use history of Melbourne were incorporated into the design of specific locations. Student projects connected this long view to the Indigenous perspective of looking seven generations into the past and into the future.

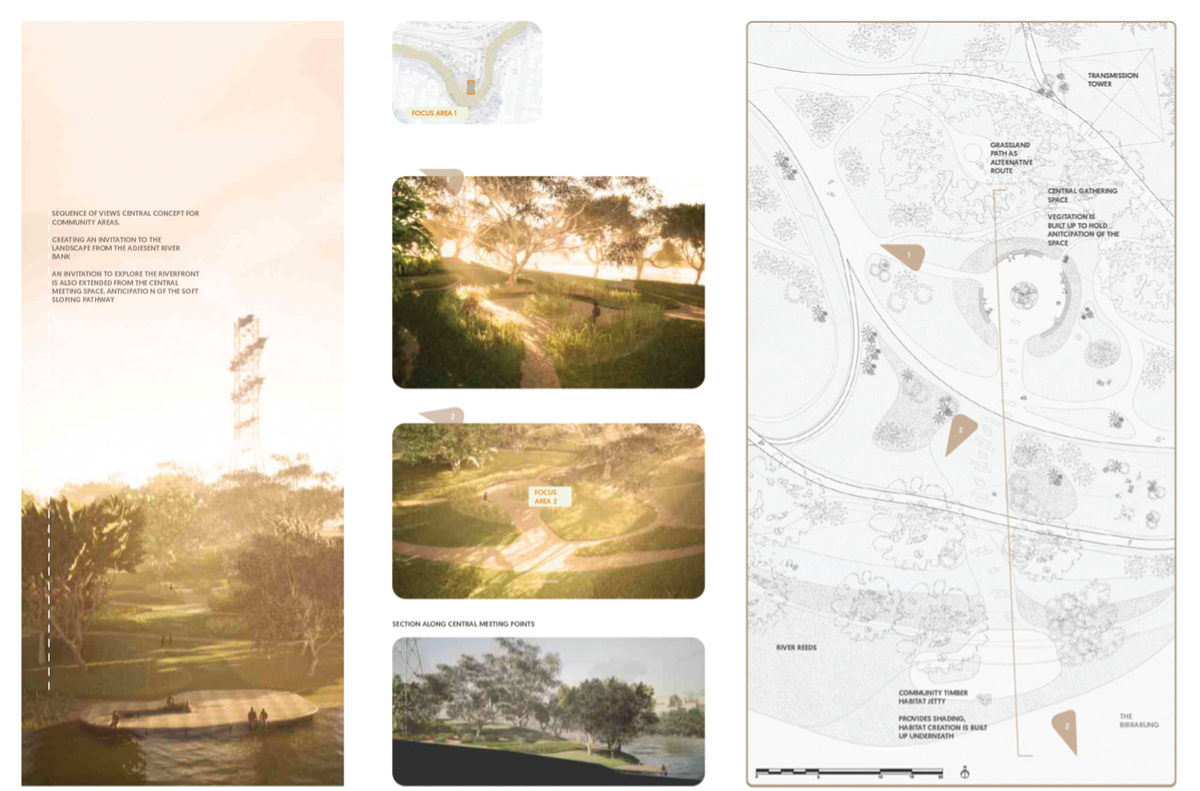

Student Gina Dahl’s project focused on Loy’s paddock, the home to the Loy Brothers Pty Ltd. Dahl discovered, in consultation with Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Elder Uncle Dave Wandin, that the creation of a contemporary cultural landscape that would be designed to educate Indigenous adults seeking to re-learn their heritage could be tied to the recent Australian history of the site as a place where soda was once produced. Uncle Dave had fond memories of his own of drinking Loy’s as a child.

The Designing with Country: Resilience Studio explored the Indigenous perspective of looking seven generations into the past and seven generations into the future.

Image: Project work by student Gina Dahl.

Student Gina Dahl’s project for the Designing with Country: Resilience Studio sought to integrate picturesque landscapes with spaces for Indigenous gathering and learning on Country.

Image: Gina Dahl

The studio sought ways of retrofitting the urbanized areas of the city to make room for the river and celebrate the historically significant spaces along it, both from an Indigenous perspective and from a more recent perspective. It sought to see things through distinct lenses not hindered by practical near-term problem solving. Students were able to link cultural sensitivity and the recognition of deep time and a long historical perspective with urban design and adaptation strategies that can support reconciliation through changes in land ownership.

Design approaches sought to repair fragments of the Birrarung that have been damaged or otherwise altered through development practices. Healing and restoring cultural, spiritual and physical flows informed the designs. For example, student Virginia Overell suggested a muyan (silver wattle) festival as a “cue-to-care” for Country. These wattles are the first to bloom and were said to be flowering when William Barak passed away. Planting them along the Birrarung creates a physical space that amplifies Indigenous identity and creates a space to celebrate Traditional Owners and for storytelling. The planting design in the public realm triggers Indigenous activity and connection to Country during the proposed muyan festival. This approach reinforces the value of public spaces as areas for storytelling and for holding other types of gatherings.

Designing for the long-term

Long-term strategies for climate resilience should consider: 1) the physical terrain; 2) green infrastructure and conservation and regeneration of existing ecosystems; 3) the built environment; 4) the inhabitants, their culture and society; and 5) climate and weathering processes, including past, present, and the anticipated future. Addressing these issues requires a team of experts – including landscape architects, urban designers and geographers – who can work in close coordination with the community. The UEDLAB work in Connecticut included, at various stages of the adaptation, staff and students from four Yale departments: Forestry and Environmental Studies, Engineering, Architecture, and Public Health. Later the UEDLAB partnered with the Connecticut Institute for Resilience and Climate Adaptation within the Department of Marine Sciences at the University of Connecticut, working with oceanographers, spatial modellers and planners to develop similar work. The Birrarung studio included multiple Indigenous design voices as well as non-Indigenous designers with experience working with Indigenous groups. We also met with Traditional Owners and council members along with representatives from Melbourne Water and other government agencies. These broad discussions increased the designers’ ability to understand the multi-faceted challenges and to create design solutions that navigate obstacles and synthesize distinct perspectives and different interests.

Landscape architects also approach design temporally, recognizing past, present and future conditions. While near-term investment strategies often focus on problem-solving and on rebuilding what existed before, it is important to keep in mind the long-term future of the spaces being designed today. Opportunities for future adaptation tend to occur in zones, clusters, or patches. The individual homeowner is not the ideal decision-maker because what happens on one property impacts the properties around it and ‑because today’s owner will not be the owner tomorrow.

Work on climate adaptation and coastal resilience has expanded in the United States, building on the development of green infrastructure, living shorelines, large parks and urban climates and other initiatives. Expertise has broadened considerably through federally funded initiatives, including the Rebuild by Design and Resilient by Design programs in New York and San Francisco, respectively. For landscape architects in Australia, there is a need to expand into this space. To do so will require building relations with the CSIRO and other geospatial modelling and planning agencies across governments around climate adaptation. There are also opportunities to consider practices across Asia and expand practices to countries with extensive urban populations in low-lying coastal and inland flood zones. The Australian government could support the increased involvement of landscape architecture in this space by establishing programs that build on international models and position designers as leaders in consultation with engineering firms, rather than defaulting to engineering firms leading the projects. The collaborative model is still being developed in the United States. It may be that Australia, given its size and the interconnected nature of its design and engineering communities, could leapfrog the United States. For Australian landscape architects, climate adaptation should not just focus on sea-level rise and flooding – drought, wildfires, urban heat and food security are all pressing climate adaptation issues that will certainly benefit from landscape architects working in that space.

Source

Practice

Published online: 6 Nov 2022

Words:

Alex Felson

Images:

Alexander Felson,

Gina Dahl,

Project work by student Gina Dahl.,

Virginia Overell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022