While visiting Tokyo – one of the densest cities in the world – I found myself standing in a public playpark created to facilitate children’s unstructured, nature-based play. As you walk through the gates, you observe a joyful and exhilarating array of activities. Scattered among the trees are a mud kitchen, a zip-line, a secret tree house and makeshift cubbies used by children of all ages and abilities: the type of play that childhood dreams are made of.

There are about 80 such playparks in Tokyo, offering every child in the city access to nature-based play facilitated by trained staff. After school, children often walk or ride to their local playpark, where staff offer them snacks and hot tea and encourage them to play and socialize, which builds their sense of belonging to their community. To me, this is a benchmark of a great city: one that is designed to facilitate rich, meaningful childhood experiences for our youngest citizens.

Designing neighbourhoods where children can play in nature is increasingly critical as cities densify and open space becomes more precious. In many Western countries, the physical landscape has changed, and children now spend less time playing outdoors.1 This trend is noticeable here; most Australian children spend fewer than two hours playing outdoors each day – 36 percent less time than previous generations – and they are significantly less likely to walk or cycle to school.2, 3

Children’s play and mobility depend on their physical environment, so how can we design neighbourhoods where children can thrive?4 Below are a few “small” urban interventions that can profoundly impact the health, wellbeing and happiness of children.

After school, children in Tokyo often walk or ride to their local playparks, where trained staff provide supervision (and snacks).

Image: Daderot, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Design for the independent movement of a child

Walking or cycling to school enables children to connect with friends and place, yet among OECD countries, Australia has one of the lowest rates of these activities.5 VicHealth principal adviser Lyn Roberts says Australian children are some of the most “chauffeured” in the world, with the number of them using active transport declining by 42 percent since the 1970s.6 Though the issues related to this decline are complex, neighbourhood design can play a big part in reversing the trend.

It has done so in Paris, where in 2020 the city introduced Streets to Schools (“rues aux écoles”). Rather than these streets being closed only at pick-up and drop-off times, they are always off-limits to motor vehicles. Where such closure is not possible, vehicles must not exceed walking speeds. There are now 180 pedestrianized streets, and 50 more are planned. London’s School Streets initiative had similarly profound results – in fact, in Hackney, walking increased by 30 percent and biking by 51 percent, while tailpipe emissions dropped by 74 percent.7

By making children – not cars – the priority users on our roads, we can normalize children playing, cycling and walking on local streets. If every new masterplan had to demonstrate how its public infrastructure would facilitate children’s ability to safely walk or cycle to school, our neighbourhoods would be very different. Safe streets outside schools, ideally alongside a network of children’s travel routes and programs, can reduce pollution and encourage active mobility, which in turn will significantly improve children’s health and happiness.

Infrastructure which facilitates children’s active mobility including signage, graphics and traffic calming measures.

Image: Natalia Krysiak.

London’s School Streets program increased childrens’ rates of walking and biking in Hackney.

Image: Hackney Council/Gary Manhine.

Create playful communities

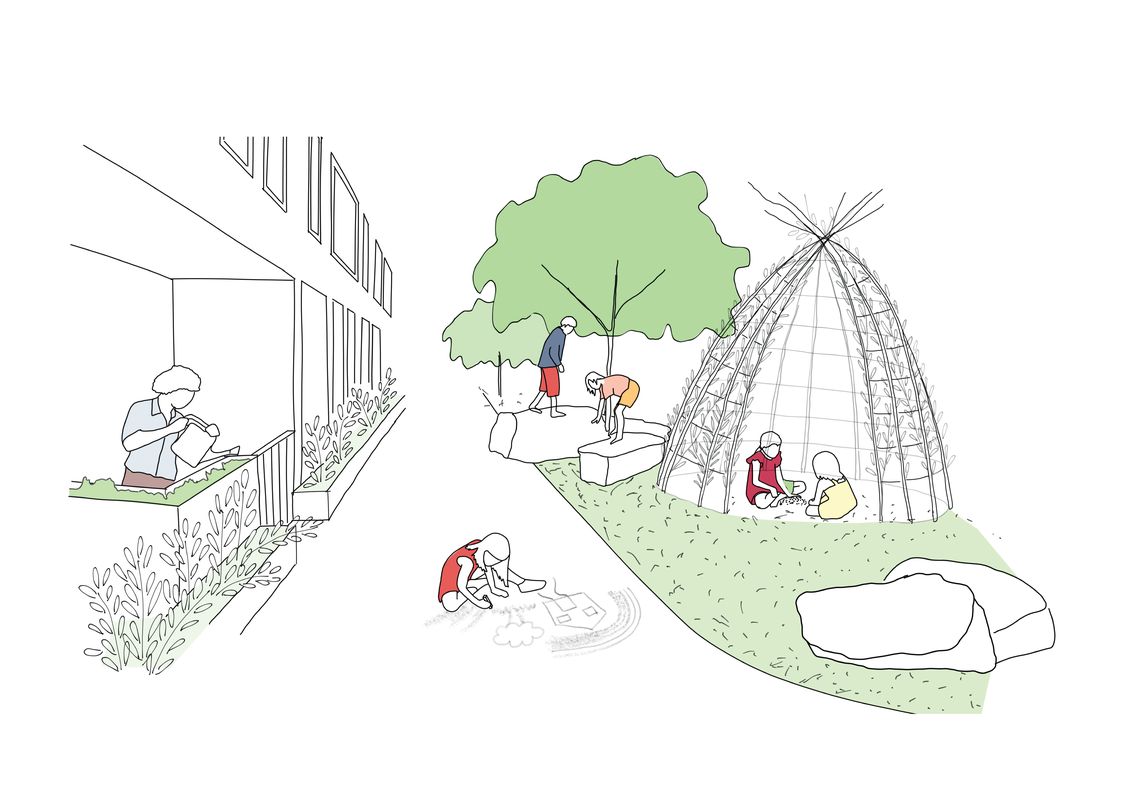

As designers, landscape architects and planners, we still regularly turn to the “catalogue” playground as though it is the only option to encourage play within public space. This infrastructure response – a playground enclosed within a fence and zoned away from other public functions – isolates play, often with equipment intended exclusively for young children and their parents. Neighbourhoods should be designed as a tapestry of play opportunities naturally weaved into the everyday life of communities, encouraging residents of all ages and abilities to socialize, play and connect as natural parts of their daily lives.

A great example of a play space that promotes community belonging and connection is the communal toy box, which is common throughout the city of Rotterdam. Called “duimdrop,” the toy boxes are small structures filled with games, bikes, sports equipment and crafts. Duimdrop are managed by playworkers, who are paid by the local council to look after the equipment and manage the space, and volunteers (often retirees). In addition to managing day-to-day activities, playworkers and volunteers also run seasonal community events – such as reading clubs, sporting games and crafting socials – to encourage community connections.

The open-ended toy box infrastructure encourages intergenerational play. One might observe children rollerskating alongside teenagers playing a casual ball game and elderly people playing cards. The range of equipment on offer allows for a truly inclusive play experience, where children and adults of all abilities and backgrounds can engage in a type of play that is in line with their interests and abilities.

Open-ended toy box infrastructure encourages intergenerational play with a range of equipment that engages people of all abilities

Image: Natalia Krysiak

Rethink the traditional “backyard”

With more families with children now living in high-density dwellings, the traditional backyard where children access daily outdoor play is not a broadly viable option. In such cases, safe and accessible communal play spaces – both indoors and outdoors – are paramount to urban livability.

Minimum play space provision should be regulated through planning policies and design guidelines to ensure that the health and wellbeing of children living in higher densities is not compromised. Cities that regulate these standards include London – where guidelines stipulate at least 10 square metres of open play space per child for new multi-unit residential developments – and Toronto and Vancouver, which set minimum areas and design qualities for outdoor play spaces in apartment complexes.

To date, no Australian city has guidelines addressing the specific needs of families with children living in apartments, and acknowledgements within existing apartment design guidelines lack meaningful consideration or statutory weight. Nonetheless, there is a promising shift toward health institutions and local councils recognizing the importance of minimum standards that address the needs of families with children in higher-density living.

Most notably, the Western Sydney Local Health District (comprising the local government areas of Camden, Campbelltown, Fairfield, Liverpool, Wingecarribee, Wollondilly and Canterbury-Bankstown) is currently in the consultation phase of its “Healthy Higher-Density Living for Families with Children” guidelines. The guide addresses the needs of families with children through a series of design considerations that range in scale from apartments to entire neighbourhoods. Considerations such as playable local streets, child-friendly travel routes and family-friendly apartments are outlined, providing benchmarks for designers, developers and councils. This design guide will be the first of its kind in Australia and is an enormous step toward high-density living that prioritizes the needs of families with children.

The profound impact of our built environment on children’s health and wellbeing is increasingly recognized in Australia and abroad. With the densification of Australian cities and the worrying decline of children’s outdoor play and active mobility, designing neighbourhoods that consider the needs of children is paramount. Simple considerations in our built environment such as safe streets to schools, community play spaces and play provision in high-density housing will have long-lasting impacts on our youngest citizens, creating a better future for all.

1.Rhonda Clements, “An Investigation of the Status of Outdoor Play,” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, vol. 5, no. 1, March 2004, 68–80.

2.November 2016 Pureprofile survey commissioned by OMO among 1,000 parents of children aged 5–12.

3.April 2016 Lonergan poll commissioned by OMO among 1,025 parents of children aged 5–12 and 1,025 children aged 5–12.

4.Thomas G. David and Carol Simon Weinstein (eds.), “The Built Environment and Children’s Development” in Spaces for Children (Boston: Springer, 1987).

5.Garrard, J. (2016) Walking, riding or driving to school: what influences parents’ decision making?. Prepared for the South Australian Department of Planning, Transport and Infrastructure

6.Louise Hardy, “The Road Less Travelled: The 2015 Active Healthy Kids Australia Progress Report Card on Active Transport for Children and Young People,” Active Healthy Kids Australia, 2015, 12.

7.“Mayor hails success of Schools Streets programme,” London City Hall, 10 March 2022, london.gov.uk/press-releases/mayoral/mayor-hails-success-of-schools-streets-programme#:~:text=Heading_,500%20School%20Streets%20in%20place.