Anna Thurmayr and Dietmar Straub are German landscape architects living and working in Manitoba, Canada. Both work at the University of Manitoba where Thurmayr is Head of Landscape Architecture. Their research, teaching and practice is informed by a strong passion for the intersections of landscape architecture, gardening, sculpture, community work and education.

Alex Breedon – How does your work differ from other landscape architecture practices in relation to time?

Anna Thurmayr – We find inspiration in a time-based approach, not through contemporary landscape architecture, but in gardening, where time is key and where the practice is oriented around seeding, waiting, harvesting, hibernating and then starting over again. Additionally, with the privilege of working at a university, we feel like we’re not forced to compete with other studios and measure ourselves against what they’re doing. We are free to explore what we think constitutes the right response to a site and client to a depth not usually possible in private practice.

Dietmar Straub – I’d like to believe that we employ time in our projects as our co-designer. I really think it’s a collaboration between time and materials. The fact that we are working with living things that grow and die means that time is indispensable.

Folly Forest: The design uses four main materials – bricks, logs, asphalt and stones – demonstrating how simple actions can create new experiences and ecologies.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

Folly Forest: Asphalt excavated for tree-planting was transformed into bricks and reused as paving around the trees.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

Liam Mouritz – Some of your projects appear to emerge over long periods – up to a decade – while others appear almost immediately through a DIY process. Could you comment on this tension between the fast and the slow in your projects?

AT – That is an interesting observation. One could say we combine fast implementation with slow growth. We initiate change through distinctive design actions that make our projects immediately visible but allow for speculative and emergent outcomes. We want our projects to grow and degrade while allowing for flexible adaptions through time. This is what we try to nurture while working with clients who become friends over the years. It all involves attention, care and accepting that gardens and landscapes are never complete.

DS – We spend time with people that we’re working with on our projects. Really, quite some time in order to build mutual trust. And often the implementation time itself is actually relatively short.

To really find out what a client wants takes time. This is compounded by the complexity of the context, the environment and the budget available, which is usually, in our case, very low. So, it’s a long process but when we get feedback from communities and clients we hear, “Wow, this project is everything we wanted, but in a completely unexpected way.”

There’s another dimension to this in terms of how we build our projects. Very often, we do not produce construction drawings. This is usually because of a limited budget, but also it doesn’t make sense to draw details because many of our design decisions are made on-site with an intuitive response to the materials at hand. There are always some initial ideas, some foundational thinking, but when the materials arrive on site we need to respond directly to them. We will usually say to a contractor that we need a certain type of tree trunk within a certain length and when that is delivered on site we start putting the design together. In a way, it’s almost like sculpting. We work with the builders to make sure the elements of the design, for example, the tree trunks, look right, don’t move and are safe.

AB – This seems to be a commonsense approach that challenges typical construction “standards” that currently govern a lot of what is produced in public landscape architecture in North America.

AT – We’re not against standards in relation to the quality of construction or craftmanship, but we do question them in the sense of challenging “routine.” Our interest in imperfection and non-standard approaches comes from us allowing projects to be flexible.

Working in this way makes us reconsider the traditional role of a landscape architect. With these low-tech, community volunteering projects it’s clear that you can’t hire a large group of landscape architects and give them all specific roles, like landscape architect, project manager, site manager or foreman. Instead, on site, we all take on these roles together. Also, given we are usually working with inexperienced people, the design and construction method is a unique challenge. Things really need to be simple and easy to learn and build.

We have a deep respect for craftsmanship and these craftspeople follow a certain kind of intuitive standard. As a landscape architect, our craftsmanship lies not just in constructing things, but also in growing things. In being inspired by gardening and gardeners, we need to acknowledge that most horticultural standards originally came out of experimentation. The garden is a place of experiments.

DS – The times I’ve worked in a traditional office setting I missed the flexibility of being on site. When I was younger, I loved working with older landscape architects on site – they didn’t have drawings, so they had it all in their head; where to place this tree, where to place that shrub. I enjoy being in a constant conversation with materials; through talking and negotiating with clients, students and volunteers you find out what this material wants to be. Eventually, you can go to the pile of rocks, pick exactly the right one and it fits. It’s an artform. It is impossible to apply standards to this type of work – the routine way of doing things does not leave room for this kind of creative spontaneity.

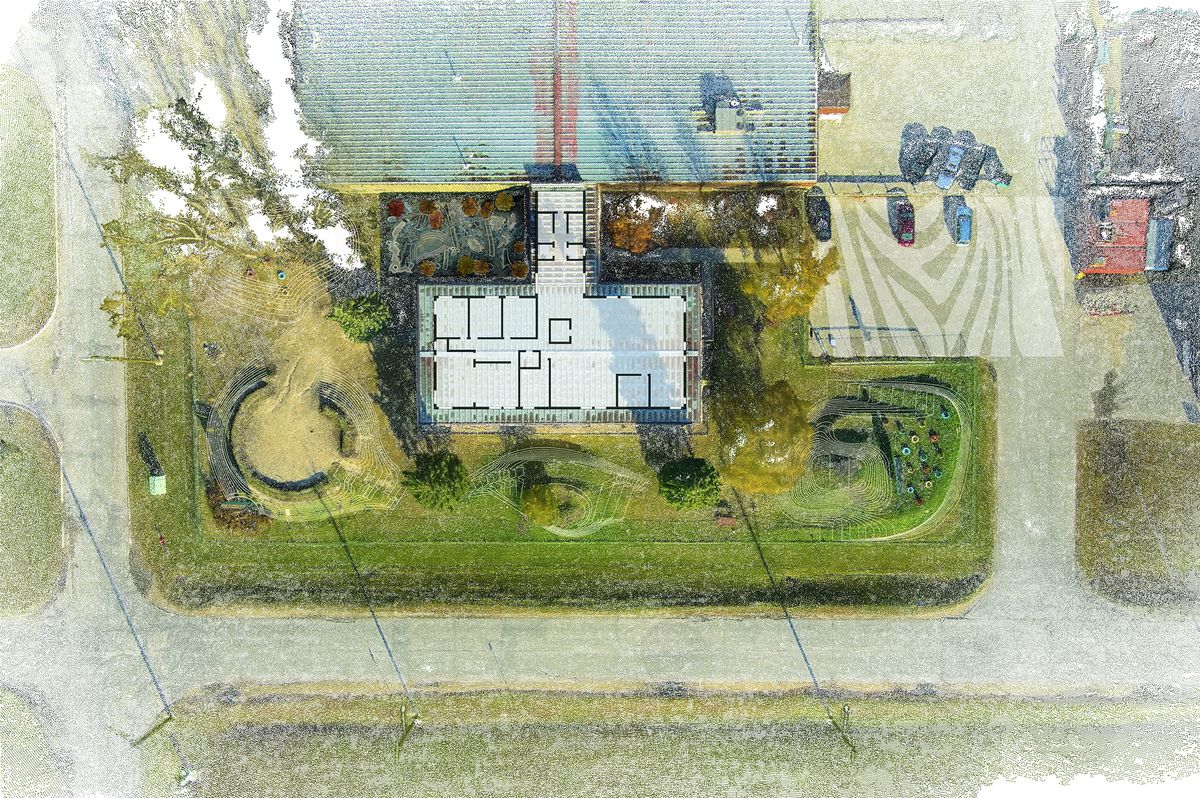

Vibrant, daring, ephemeral wild: Straub Thurmayr transformed an outdoor play space at a prairie school in Winnipeg into an experience centred around experimentation and creativity.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

Vibrant, daring, ephemeral wild: Rough terrain, overgrown grasses and loose materials characterise the space creating opportunities for learning.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

LM – Rooted in Clay is a well-known project of yours that you’ve been working with over many years. Can you describe this project in more detail?

DS – When we agreed to work with that client, we didn’t ask for money, but we did ask for the license to take creative risks. We told them, “Ok, we’ll do something for you that you will like and enjoy but we want to test some ideas.” And in a way, their garden became our testing site for ideas that we feed back into our practice. In the beginning – and we don’t tell our clients this – but we’re probably going to end up being their landscape architects for their entire life!

For Rooted in Clay, we did a few drawings and relied heavily on salvaged materials that we found. Some of these were beams from the demolished Winnipeg Arena. We travelled around to many different refuse yards and second-hand stores to find things that many people would consider useless. Materials such as salvaged timber and irregular boulders really define the post-glacial landscape of Winnipeg and informed our material palette for the garden. There are no nails or supports within the benches we designed, just intelligent placement and gravity.

At Rooted in Clay, the designers planted roots to stabilise the ground, nurtured a lush meadow of grasses and recycled old wood planks to create areas for sitting and gathering.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

Rooted in Clay: Beams of wood form picnic tables and resting areas and are held together by gravity alone.

Image: Straub Thurmayr Landscape Architects

LM – It seems as if the garden in that project was almost seeded and then left to go wild, according to nature’s processes?

DS – I admit, it does look wild, but even the “wild” look needs maintenance, care and knowledge. It’s definitely low maintenance in comparison to the typical Canadian lawn, but it still requires a gardener’s eye and temperament. Many designers are only involved at the beginning but don’t want to do any maintenance later. But, for most of our projects, we ask for continued involvement after construction. We have to acknowledge that we’re in a constant dialogue with the land, and we really insist that our clients build a relationship with their landscapes in this way too.