Estudi Martí Franch studio founder Martí Franch Batllori spoke with Alex Breedon and Liam Mouritz about slowness, resourcefulness and experimentation in his landscape architecture practice; maintenance as a design practice; and site engagement possibilities over extended time frames.

Liam Mouritz – What kind of work does your practice focus on?

Martí Franch Batllori – In Catalonia, the architectural profession is very dominant, and there hasn’t been a strong tradition of landscape architecture, particularly in regard to the design of public space. When I established the practice in 1999, it was very difficult to find work in cities, so we started in remote natural areas and villages, essentially because no other design practices were claiming this territory. The first thing you face in these places is that you have almost no money or resources. This influenced our mode of practice as we matured to focus on slow and resourceful work. It has been a long journey to get to where we are now, being able to work on significant urban projects in Barcelona. We’re working with good engineers and architects in a non-traditional way that focuses on the greening of urban spaces.

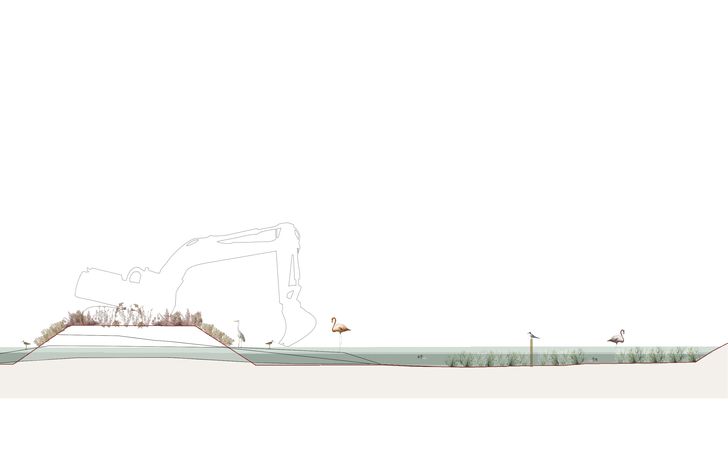

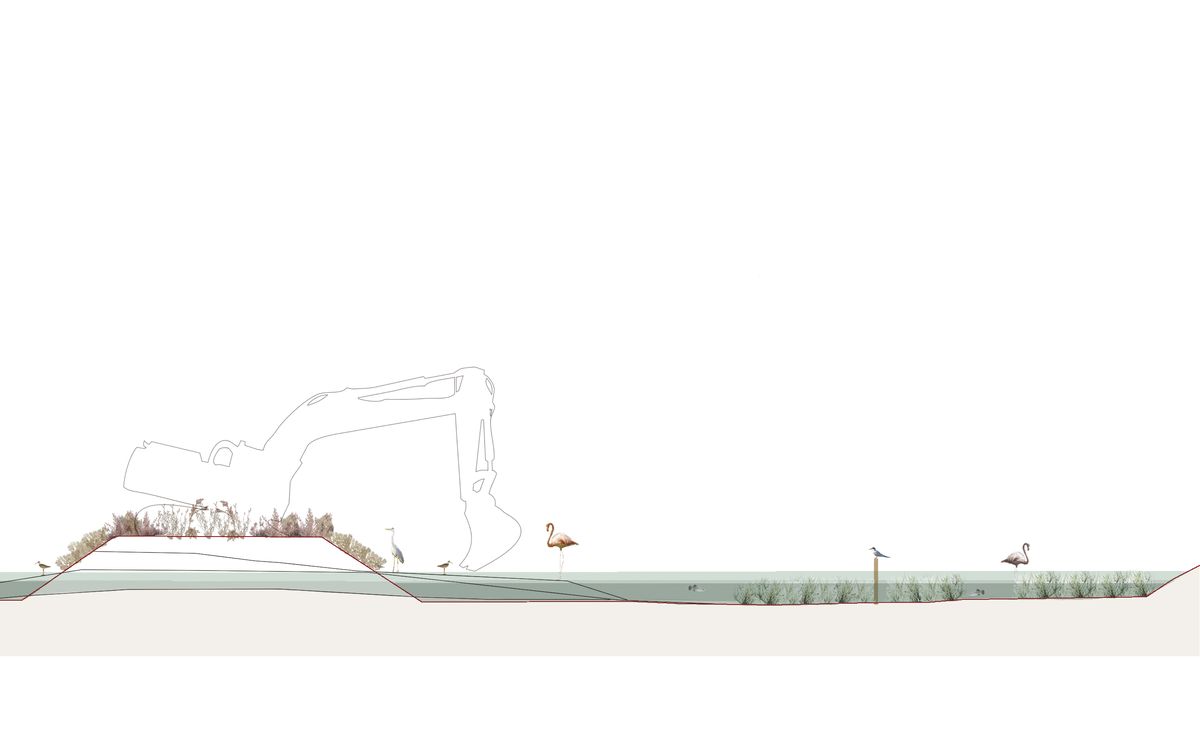

At the Salines de la Tancada, strategic excavations between pools aimed to diversify habitats without affecting existing species.

Image: EMF

From the 1980s, the salt fields were converted into a fish farm; Estudi Martí Franch’s brief was to restore the lagoon landscape as habitat for fish and bird species.

Image: Mariano Cebollo Borrell

Alex Breedon – Could you describe in more detail one of these slow, low-cost projects you worked on early on?

MFB – Girona’s Shores was developed in the opposite way to the conventional delivery of urban landscape projects. Initially, we had no defined brief. At that time, I was doing my PhD with RMIT University and I received EU (European Union) funding through the Marie Curie fellowship, allowing me to spend more time on research. I decided that I would like to focus on design by management and experimenting through built interventions. The intention was to turn space-keeping resources into space-making resources. Inspired by Gilles Clément’s pioneering “garden in movement” projects, we began to work towards creating green infrastructure at the scale of a small town.

We started immediately with a pilot project and started mowing experiments at the edge of town. Originally, I was doing this myself, as an amateur, but then later we involved the local municipality’s maintenance staff. We spent a lot of time on site with these people to define regimes of care and management and to understand the peculiarities of the site. After a while, more senior people from the council came and were impressed. After this, the council came to us and suggested we do a masterplan or framework for the whole town of Girona. We then started working on this larger project concurrently with our on-site test projects. We always had the idea that this was a larger landscape infrastructure project, but one that didn’t follow the usual urban planning process that often begins with a beautiful narrative but then fails without the tools needed to successfully implement it. Instead, our process was the reverse, starting with the tools that then progressed the masterplan.

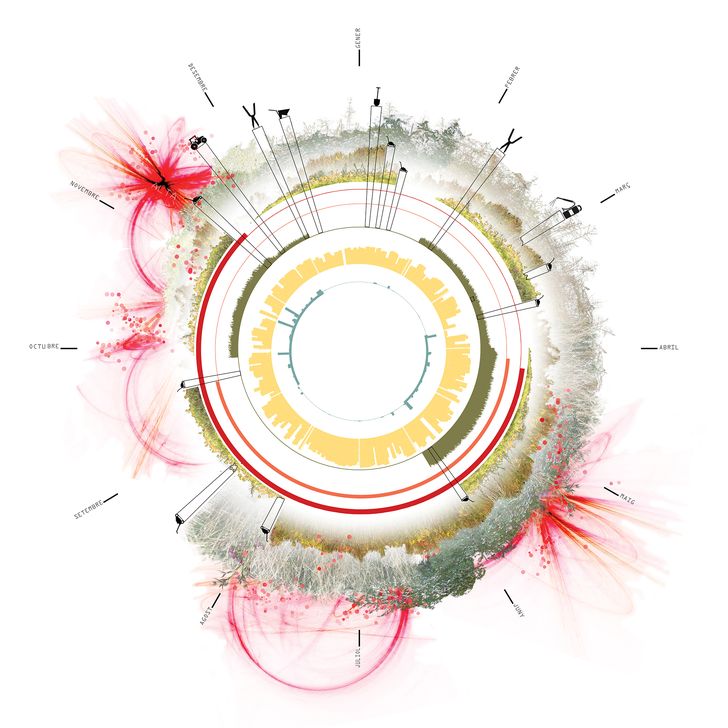

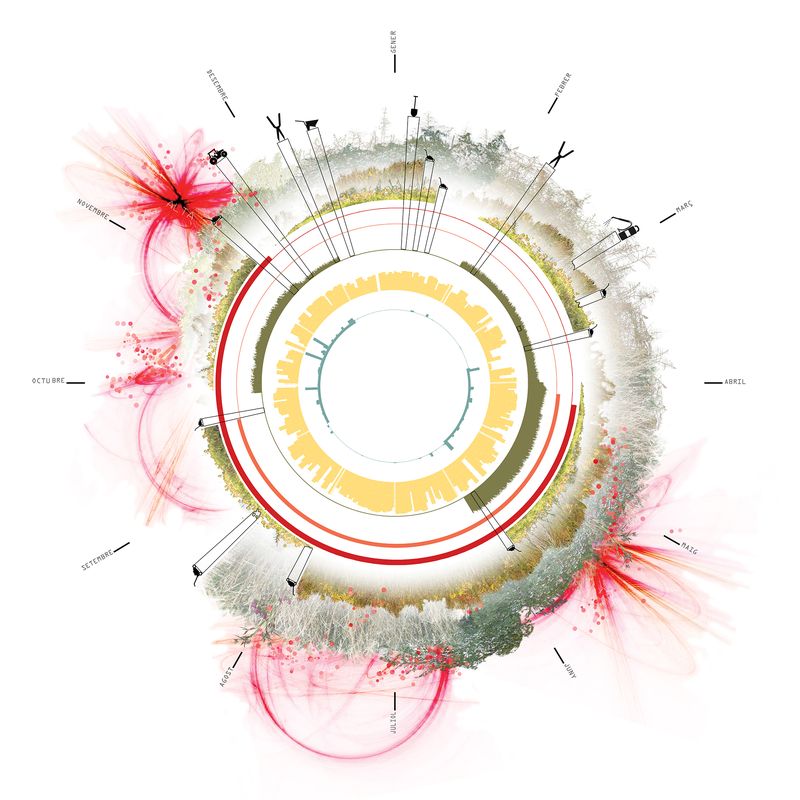

A calendar showing one year of differentiated management of Girona’s Shores. Natural dynamics – sun, rain and social use – are at the centre of the calendar; management regimes are illustrated by “cuts” (concentric radii); red bubbles mark Girona’s main cultural events.

Image: EMF (Martí Franch, François Poupeau, Mercè Pagès and Meruyert Syzdykova)

A view of the Archaeological Park in 2019. The park is one of 30 “naturban” areas planned as part of Girona’s Shores. After four years of differentiated management, the park contains a rich mosaic of woods, scrub and meadows.

Image: Martí Franch

The project really focused on tactics rather than strategies. We had a tactics sheet that was jointly developed with the head of the maintenance team that aimed to diversify the order of the activities undertaken by the maintenance team on the ground by using a series of “if/then” guidelines. Because every scenario is impossible to predict, a sequenced way of implementing ideas on site was important. Now the gardeners who manage the land have a framework that guides them, and I would say that every year the landscape is more beautiful and expansive. Currently, they are working on45 hectares, but the ambition [. . .] is to transform 600 hectares throughout the city.

We also invited cultural event programmers to use the space, to encourage people to visit this fringe part of the city. The best event is a land art festival, held since 2018, where many of the sculptures are placed within Girona Shores. Previously, we had engaged with Girona’s Federation of Citizens Association to develop a path system that would connect 23 neighbourhoods without going into the centre of the city. Because this is a research project, we really tried a whole bunch of initiatives to get this project to come alive.

During the COVID-19 lockdowns last year, the project really came to life as people were forced to explore what was in their immediate one-kilometre surrounds. In this sense, the city of Girona has become bigger, purely because people have been using and discovering public open space around them at the “shores” of the city.

LM – In comparison to Girona’s Shores, are there any projects where there have been some unexpected transformations since you completed the work?

MFB – Yes: Les Echasses, a landscape “nature-luxury” resort near Hossegor, France. I hadn’t been to the project for over six years, so when I went back in 2022, I was amazed. It was so beautiful the way the landscape had emerged and taken over the site, with the care of the owner.

The site was initially a flat six-hectare cornfield with a small irrigation basin. When we visited it for the first time with the architects, we thought there was a lot of opportunity here to increase the biodiversity, to help create an amazing tourist experience. Our starting point there was to think, well, instead of maintaining this flatness, let’s create a topographic and undulating waterline, multiply the littoral to exaggerate and play with what was already an artificial landscape. The soil there is sand, and the water table is shallow, so it was very easy to shape. Through this topography, we defined a landscape where different types of chalets could be placed according to the landscape condition: some overlooking the water, others on a dune, on a beach or in a prairie.

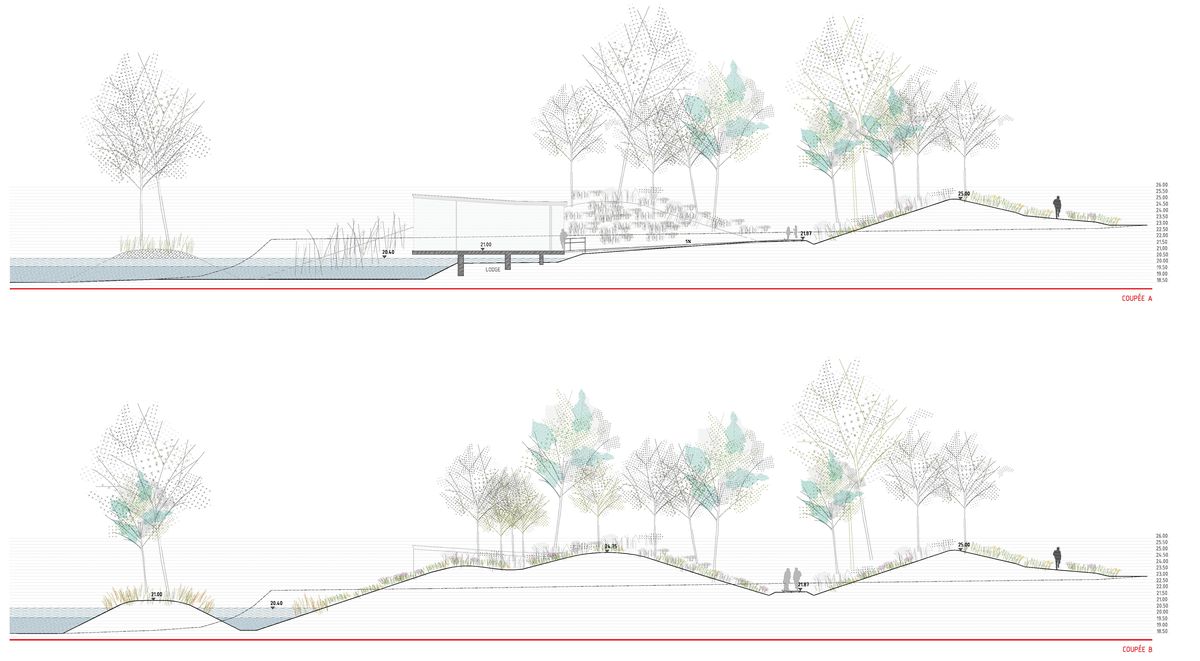

At Les Echasses, a luxury nature resort near Hossegor in France, a flat wheat field with a small irrigation basin has been transformed into undulating wetlands that are richly biodiverse.

Image: Patrick Arotcharen

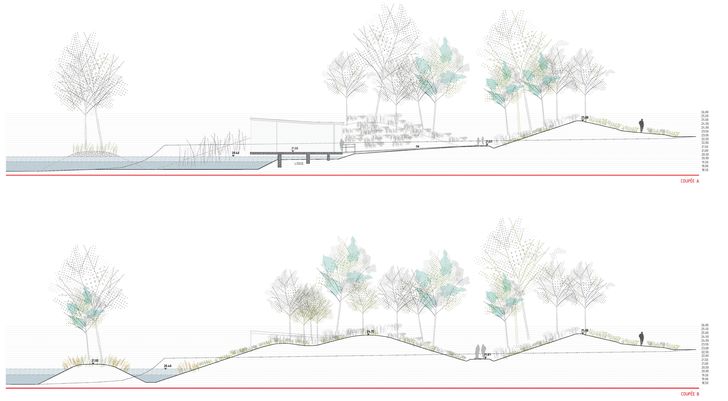

At Les Echasses, 23,000 cubic metres of sand was reprofiled to create a new liquid landscape where pavilions are sensitively sited within a dune topography.

Image: EMF

AB – In comparison to an approach involving defined maintenance regimes, how is time approached at Les Echasses?

MFB – In this project, we put in place many of the big moves at the beginning. In this way, it was more about the curation of an ecological process to help the site become more abundant over time. However, it is not completely wild; there is a very simple maintenance strategy. The areas which are flatter near the paths are cut more regularly, while the dunes created by the lake excavation have much larger, denser vegetation and are cut only once a year. What’s really interesting about this is that the owner has taken on this management of the site himself, and through this, it has become more and more his own creation.

LM – What do you think prevents landscape architects from having deep, long-term involvement with the landscapes they design?

MFB – One of the biggest issues here in Catalonia is the way that our contracts are arranged with clients and particularly governments. Actually, just last month [in February 2022], we managed to secure a contract for four years’ involvement in a site – to prepare and execute a series of interventions and maintenance regimes. In most projects, we are forced to make a lot of the decisions at the beginning, then pray that things will go as planned. But with this project, we can do less at the beginning, wait a bit, check it out again, then do a bit more. Using the lessons learnt from our previous actions, we will certainly do things differently the following time. The point of this is to give ourselves the flexibility to adapt to changes as they happen. This requires new contractual forms.

Source

Practice

Published online: 2 Sep 2022

Words:

Liam Mouritz,

Alex Breedon

Images:

EMF,

EMF (Martí Franch, François Poupeau, Mercè Pagès and Meruyert Syzdykova),

Mariano Cebollo Borrell,

Martí Franch,

Noam Debel,

Patrick Arotcharen,

Sergi Romero

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022