Alistair Kirkpatrick – How important is the relationship between soil and vegetation?

Simon Leake – It’s critical. We’ve got to understand that vegetation makes soil. It’s almost a self-fulfilling prophecy: you start with weathered rock, vegetation grows on it and accumulates nutrients, and those nutrients are recycled back into the topsoil so that the vegetation can accumulate the nutrients it needs. Soil scientists talk about “Jenny’s equation,” which says that soil is a function of the biota – the plants and animals that live on it, the topography, the geography, the climate and, most importantly, time.

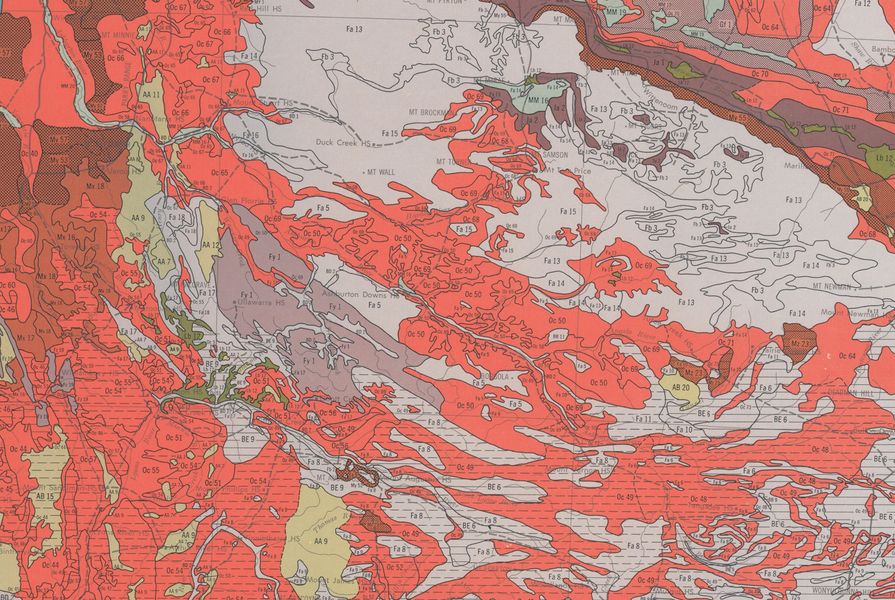

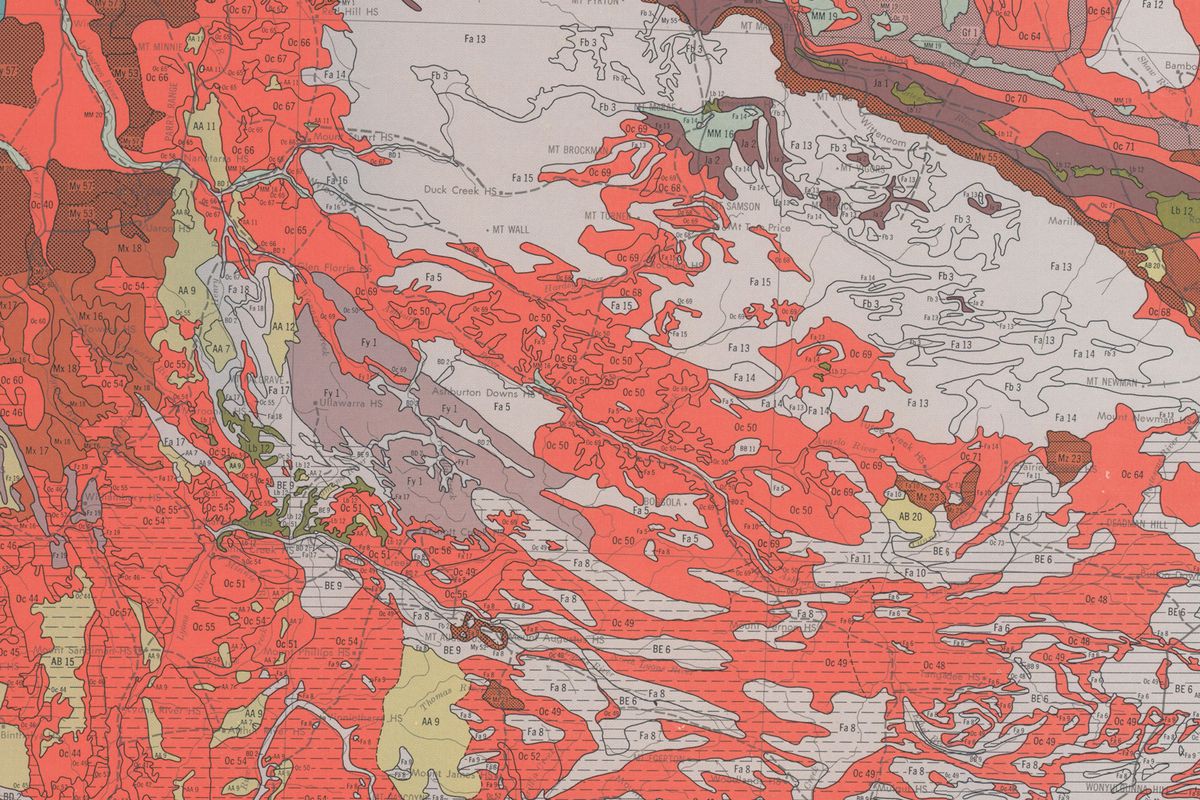

Mount Tomah and Mount Wilson in Sydney [Blue Mountains] are located on basalt cap soils. The drive to these basalt caps is through scribbly gum sandstone flora, a low-fertility plant community that is sparse and open. You encounter this wall of magnificent timber when you cross into the basalt geology. This is a prime example of soil and vegetation working together

on geology.

Simon Leake is principal soil scientist and managing director of SESL Australia.

AK – How important is it for landscape architects to have plant knowledge in order to successfully engage in planting design in urban soils?

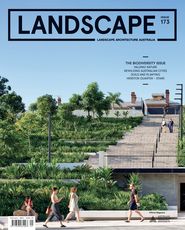

SL – Obviously, plant knowledge is critical. But I’d hesitate to expect every landscape architect to be a specialist in every area. The two leads on the Barangaroo project that I worked on in 2012, Adrian Pilton [of Johnston Pilton Walker] and Peter Walker [of PWP Landscape Architecture], did not have a particularly strong knowledge of the Sydney sandstone flora but they engaged people who did – Stuart Pittendrigh, who is a landscape architect and also a horticultural expert on the Sydney sandstone flora, and me. Johnson Pilton Walker and PWP did the design and Pittendrigh and I allocated the plant communities within that design. I think a certain minimum of plant knowledge is absolutely necessary, but you need to know what you don’t know and when you need to get help.

Leake and landscape architect Stuart Pittendrigh drew on their specialist knowledge of soil and horticulture in allocating plant communities at Barangaroo.

Image: Brett Boardman

Barangaroo headline park project was developed through planting trials with Sydney sandstone flora.

Image: Brett Boardman

AK – What’s changed in the industry over the course of your career?

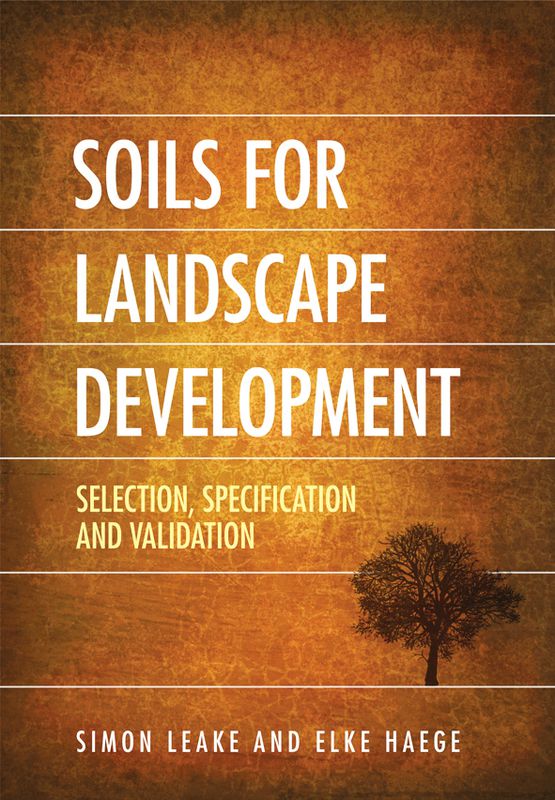

SL – When I started working in 1984 there were virtually no specialists in urban soil science. There are still very few – I can name maybe three or four – but when I started, there was just me. We need to recognize that soil is a speciality in its own right. Many landscape architecture firms use me on a collaborative basis on every project they do. Others think they can do it all themselves (plants are pretty forgiving, unfortunately, so a lot of the time they get away with it!). There is no commercial soil produced in Sydney that would have been suitable for the Barangaroo project. The quality of commercial soil mixes is not what it needs to be, although thankfully it’s getting better. The soil yards are taking on the book I wrote with Elke Haege – Soils for Landscape Development.1 Many of them don’t like it because [the requirement to test is] complicating their job, but many of them are taking it on with the view to improving their soil products and engaging in best practice.

AK – Do you think that soil could be thought of as a historic artefact, like an archaeological monument?

SL – Absolutely. There was a final-year thesis subject run at the University of Technology Sydney [in 2020] that was specifically about the vegetation edaphology of an area of old sand-dune country that is currently a golf course near central Sydney. It was within the landscape architecture department and was led by Martin Bryant and called “Rewilding Moore Park.”

I was asked to give a presentation on the soils of the area, which are very characteristic “Podosols” that form on sand dunes. They’re beautiful soils. I explained to the students how incredibly interesting the soil under sand dunes is. The soil under the dunes is over 10,000 years old and is separated into spectacular horizons. Only two of the student groups specifically discussed the soil types and their preservation in their thesis. I don’t think I have seen soil preserved for its own sake in any project I have ever worked on. It’s not traditionally considered by archaeologists as worth preserving.

AK – What is your favourite type of soil?

SL – My favourite soil is called “black earth” in the old language. It forms on basalt and is jet black and crumbly and cracks up beautifully. It’s rare in New South Wales, even rarer in Sydney – the few pockets that did exist have been extensively mined for the basalt beneath them. In Sydney, the Australian Society of Soil Science tried to get the last major deposit of black earth – in Prospect – preserved, and they failed. There is still some left next to a creek flat that I know of, and I’m working on restoring some black earth soils in an old basalt quarry in Hornsby. The place is called “Old Man’s Valley” and is a mined-out basalt diatreme. Here we are going to showcase the edaphology of the soils and their associated vegetation. It’s a very exciting and forward-thinking project – everyone interested in landscape should keep their eye on it. I would love to design a staircase that descends into the earth so people could see the horizons of soil – they’re spectacular, beautiful. There is no tree as old as the youngest of soils.

In 2014’s Soils for Landscape Development, Leake and Elke Haege made the case for specifying landscape soils based on scientific criteria.

AK – There has been a lot of interest lately in the role of subterranean fungi and microbes in healthy soils. Of the products now available that claim to inoculate soils, what, in your expert opinion, is fact and what is fiction?

SL – We know that fertile soils are very biodiverse but desert soils are not very diverse, which reflects their different climates and geologies. We also know that subterranean biota systems are incredibly complex. The two most important associations we know of are rhizobium bacteria associated with legumes; and plant species with commensal mycorrhizal fungi.

Rhizobium bacteria that live on the sugars produced by the legume plant fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and release it into the soil, benefitting the plant. But not all rhizobia fit all legumes – you need specific species. We know how to select particular rhizobia for particular legumes – for example, a particular species of rhizobium that will inoculate clover will do nothing for a wattle.

The same occurs with mycorrhizal fungi: Allocasuarinas have a specific relationship with one species of mycorrhizal fungi that allows the Allocasuarina to access phosphorus in poor soils. The University of Newcastle did some research on mycorrhizal associations. They inoculated 12 or 15 species of colonizing plants used for mine rehabilitation with 6 or 8 species of mycelium and found that only 20 percent of the associations proved demonstrably beneficial. You need to infect the right species of plant with the right species of mycelium. That knowledge is not nearly as well understood or as sophisticated as our knowledge of rhizobium.

When you see people waving little pots of mycelium and mycorrhiza around and infecting the soil with it, there are two things to keep in mind: the first is that the mycorrhiza is unlikely to be the correct species to create a beneficial association with the plants you are wanting to grow, and the second is that mycorrhiza are only beneficial in poor soils. Mining companies want to find the right acacia inoculated with the right mycorrhiza that will grow on their mine waste without having to pay for fertilizer.

[The University of Newcastle’s] research is valuable because it is not always possible to add large amounts of organic compost and fertilizer in rehabilitation projects. So, just adding a mix of micro-organisms and fungi to a poor soil is usually ineffective – they need something to live on. By adding compost alone, you’re providing the fuel that micro-organisms need. They will then colonize the soil without you adding any. There are spores in the wind everywhere that will colonize soils with good organic matter contents.

When I was developing the soil for Barangaroo, I conducted plant trials. I suspected that many of the Sydney sandstone flora would have relationships with mycorrhizal fungi, so I added 5 percent leaf litter from a nearby forest to the soil mix for the trial – and there was no observable difference. I’m not ruling out the benefits of inoculation, but none of the plants growing at Barangaroo were inoculated and they’re all growing very well. However, some mycorrhizal fungi is naturally present in seed – as with Allocasurina – and it is dispersed by the wind. So, this helps plant growth without you knowing about it or doing anything.

Allocasuarinas have a relationship with a type of mycorrhizal fungi that enables the trees to access phosphorus when soil conditions are poor.

AK – Many urban soils become alkaline due to contamination from building waste. Could this be seen as an opportunity to showcase a suite of plants that thrive in alkaline conditions?

SL – There isn’t a week that goes by that I don’t have to deal with alkaline soil. There are several reasons for this. One is that our cities are covered in concrete, and even the water flowing over the concrete is alkaline, which decreases the acidity of soils in bushland valleys, leading to conditions that privilege weeds over native plants. Also, a lot of recycled soils come from urban environments that contain builder’s lime and concrete, leading them to be alkaline. We can acidify soils, but if the soil is more than one percent lime, it’s not economically viable to do so.

My biggest aim at Barangaroo was to avoid any lime contamination, including avoiding using sandstone that contains lime. The quarry rehabilitation project in Hornsby is an interesting case study, as basalt is naturally alkaline but the soils that form from it after 10,000 years are acidic. We conducted plant trials for Hornsby council and all the plants, bar one, adapted well to higher alkalinity.

In New South Wales, there is a resource called E-spade, which provides information about the soil where a plant grows in its natural range. A knowledge of the soil on-site, and its vegetation, should always be part of your site investigation. Landscape architects undergo extensive site analysis, but many don’t dig a hole.

AK – What do you see as the future of urban modification and soil science in the face of accelerating climate change?

SL – We know we need to increase green cover in urban environments. There are two aspects to this. The first is how we create root zone [rooting volume and rooting space]. Emerging techniques are structural soils, plastic support cells, green roofs and walls – and we need more research and trial work in this area. The second is how we retain water. In a natural green environment, it’s not the plants that keep the environment cool, but the water they evaporate through transpiration, through the leaves – it’s the latent heat of evaporation. Evaporation from the soil itself plays a minor role. Water-sensitive urban design (WSUD) has been hijacked by those who want to clean the water up, then chuck it out to sea. I think that’s wrong. We need to use this water to charge our urban soils, with water, and retain water bodies in landscapes, to cool our cities.

Crown Street Wollongong is a great example of water harvesting. The water that is captured from the impervious surfaces is directed to soil to recharge the groundwater; once the groundwater is saturated, it flows into storage tanks.

Even though we are the driest continent on Earth, Sydney is not dry – we have a metre of water! The issue is reliability of rainfall – you’ll get three inches overnight then nothing for six weeks. In nature, it’s soil that stores that water. We need to get more functional soil into cities and design, so that water is retained, so these soils can absorb it quickly and retain it, so vegetation can then use it to transpirate and cool. Remember, one cubic metre of soil can retain around 200 litres of water.

Healthy soil that can sequester carbon only occurs in the absence of modern agriculture. We have to preserve existing forests and create new forests and integrate them into our urban and rural spaces.

I will leave you with this thought: if you look at many environments in Western Sydney, Western New South Wales and parts of Victoria, there are more trees now than there were in the 1990s. This is a result not just of government policies and land preservation, but better agricultural practices involving less clearing and better understanding of the role of remnant forest by farmers and land managers generally. We need to continue to increase tree cover and leave in place leaf litter in the parks and reserves of our cities so that soils can function and evolve again.

1. Simon Leake and Elke Haege, Soils for Landscape Development: Selection, Specification and Validation (Melbourne: CSIRO Publishing, 2014).

Source

Practice

Published online: 30 Mar 2022

Words:

Alistair Kirkpatrick

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022