Formal landscape architectural education in Australia only began in the late 1960s and it seemed to adopt a relatively unmediated British approach, with an overlay of Australian environmentalism.

Historically, landscape design has a long tradition of chauvinistic nationalism. The Brits were always scathing about the axiality of French-designed landscapes and Aussie landscape architects took on this attitude without question, with the design ethos of the 1960s Sydney Bush School style. The Chicago adaptation of French Beaux-Arts was grudgingly accepted in the designs of Walter Burley Griffin, despite attempts to turn the triangulated pivot points into eighteenth-century English landscape follies, and Marion Mahony Griffin’s drawings were heavily mediated by nationalistic bush icons.

We admired the restraint in Japanese gardens and Roberto Burle Marx’s exuberant Brazilian designs and in the late 1970s, we also became interested in the practice of landscape planners in the USA and started to teach about their work in landscape programs. But in the main, we maintained an Australian focus on plants, the environment and design. It was not until mid-1980s postmodernism that emerging Australian landscape architects allowed for wider international influences in design. The student profile at this time typically reflected Australia’s wider multicultural community, but there was little encouragement to explore such cultural diversity in design and planning.

All this changed in the late 1980s, when universities began to take on economic rationalist policies. Through the 1990s and 2000s, universities attempted to break down discipline silos by rationalizing course units into university-wide uniform credit points, which assisted with costing the delivery of degrees. A program was established for efficient marketing of Australian degrees, particularly to China and South-East Asia. As the Australian Government pursued this model for funding the tertiary sector, more and more Chinese and South-East Asian students enrolled in full-fee-paying degrees. Economic rationalism also included outsourcing English teaching for overseas students.

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), with its long history of accepting overseas students through the Colombo Plan, was quick to enrol Chinese and South-East Asian students. When I left UNSW in 1996, there was a growing number of full-fee students in landscape architecture master’s degrees. These were new masters by coursework degrees that could be completed in a year, with an extra six months for individual projects.

In the competitive environment to enrol full-fee-paying overseas students, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) did not have the pull of the “sandstones” in Sydney and Melbourne. In 1997, the new dean of the built environment faculty, who was Chinese but educated in the USA, proposed that QUT design students go to China for a month-long studio at a design school in Hangzhou. In return, QUT would host four design lecturers from China for three months the following year. This program facilitated some meaningful intercultural exchanges and operated successfully until the dean retired. Similar student exchanges occurred with the University of Western Australia and RMIT University. Interestingly, the following dean at QUT had a strong interest in Lesotho, Africa, and funded biannual workshops on infrastructure projects in the field in Lesotho. As the wider faculty included engineers and construction managers, only a few landscape architects participated in this international venture.

At QUT, a growing connection with the landscape students at the Universität für Bodenkultur Wien (BOKU) led to a Global Studio in 2003. Twelve Viennese students came to QUT for a month. The first stage, which saw the Viennese students go to Brisbane, was a highly successful part of the Global Studio, but the second stage did not occur. No QUT student took up the reciprocal offer of a month in Vienna. The Australian students, unlike the European students, were not able to get financial assistance, nor could they leave their jobs for a month, being highly dependent on the income to fund their studies. European students do not have to pay for their education.

In 2006 Tom Rivard, a lecturer in architecture at the University of Sydney, initiated his Urban Islands studio on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour. This is an independent studio and students worldwide are invited to apply. Local and overseas students, including a high percentage of Chinese and South-East Asian students, apply to the relatively inexpensive studio run over two weeks. The competition is fierce, so only those with well-developed design and communication skills and a reasonable knowledge of cultural and design theory are successful. I was invited to the final presentations in 2013, when about three-quarters of the students were Asian. I was amazed by the strong verbal presentations and discussions by all of the students. The interactive discussions around the various works drew from complex design theory, while the work itself was dense and challenging. This was international design education at its best.

Rivard continues to run the Urban Islands studio with its international students and practitioner/tutors. He reflects:

“Our international visitors didn’t hesitate to be provocative, despite being outsiders. In fact, I suspect that they WERE provocateurs precisely because they were OUTSIDERS … I also suspect that the affinity of many of our foreign students with the program stemmed from their ability to identify with their visiting tutors as fellow outsiders. Both the visiting studio leaders and their students learned together. The intensity of the program, with a minimum of ten hours of work in the studio expected each day, successfully eliminated the tendency for many students (not just foreign students) to retreat to work at home alone. This forced collegiality produced a genuine conviviality and collaborative spirit, that we find nearly impossible to replicate in a standard design studio, in which most students work remotely.”1

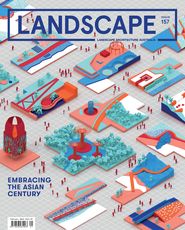

Work produced by students of the Urban Islands studio run by Tom Rivard, associate at McGregor Coxall.

Image: Tom Rivard

Internationalism has many more dimensions than bringing overseas students to study in Australia. Ideally the exchange should be two-way. At QUT, a PhD student from Tongji University, Shanghai, proved to be an exemplary ambassador for internationalism in landscape education. Her PhD thesis explores the cultural inconsistencies in interpreting and managing World Heritage landscapes. She returned to Tongji University and set up a small research hub on heritage landscapes interpretations. Such was her scholarly input to landscape architecture at QUT that one of the staff decided to learn Mandarin and do her PhD at Tongji.

In 2014 I was asked to teach a unit on heritage landscapes at Tongji University. Intriguingly, most of the students were from Europe and South America and were full-fee-paying. But the best interactions were the informal workshops with four to five Chinese PhD students who were researching the ways to understand significant spiritual landscapes within contemporary international heritage protocols. Conventional communication was a challenge; their English was rudimentary and my Mandarin was similarly basic and we were dealing with difficult concepts. We spent many inspirational afternoons drawing, explaining and discussing, using our laptops as translators, as we delved into the concepts and meanings of heritage landscapes in China and the West. This was intercultural scholarship at its richest.

Looking at landscape architecture education in 2017, we see how the deregulation of Australian tertiary education in 2009 has led to increased numbers of domestic and international students studying landscape architecture in most programs. With student places no longer capped by the government, along with the addition of Commonwealth Supported Places that support domestic students to study master’s degrees by coursework, the two-tier education system that was emerging during the 1990s (which saw domestic students studying at undergraduate level and more international full-fees-paying students continuing their studies with master’s) has shifted. This has contributed to international and domestic landscape students enrolled in the same professional courses. In addition, the profile of international students has shifted to predominantly Chinese, with a twelve-fold increase in Chinese enrolments across Australian universities since 2001 (representing a quarter of all international students).2

There is no question that these political and economic shifts have altered the delivery and experience of landscape architecture education for academics and domestic and international students. With this change comes both benefit and challenges. Difficulties can arise over English proficiency levels, with universities varying in their approach to English standards, while the international cohort challenges academics to present a globally relevant perspective on landscape architecture. On the plus side, increasing student numbers provides stronger financial support for landscape programs, which have always struggled against the dominance of architecture programs. The presence of international students also brings more culturally diverse perspectives on landscape architecture, establishes potentials for cultural exchange and breaks from nationalistic framing of landscape architecture.

End notes

1. Tom Rivard, personal communication, 29 August 2017.

2. Andrew Norton and Ben Cakitaki, Mapping Australian higher education 2016 (Grattan Institute, 2016), 24.

Source

Practice

Published online: 21 May 2018

Words:

Helen Armstrong

Images:

Tom Rivard

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2018