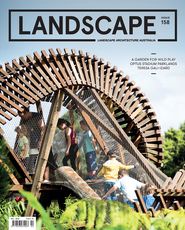

Refreshingly free of signage, the garden encourages children to choose their own narrative as they engage with the natural environment.

Image: Brett Boardman

“That very night in Max’s room a forest grew and grew and grew until his ceiling hung with vines and the walls became the world all around …”

The text and illustrations of Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are conjure up pure joy and scariness, rolled into one messy, muddy ball of delight. Many of us would like our kids to have more opportunities to safely enjoy dirt and trees; however, the pressures of city-living are making it increasingly difficult for children to engage with nature. “Nature deficit disorder” has become a genuine issue for our inner-city and suburban kids. In its 2016 report card, Active Healthy Kids Australia identified that only 19 percent of Australian children and young people aged five to seventeen years met the national daily physical activity guidelines – a troubling statistic that reinforces what many already know, that it is becoming harder to get the younger generation outside and off the screen, let alone out into nature for unstructured play.

Centennial Parklands was in a great position to make a real difference to this modern conundrum. It already had a strong education program to build from, accommodating 12,000 student visits and 20,000 community-based visits per year. When the Centennial Park and Moore Park Trust started discussions with the Ian Potter Foundation about the possibility of establishing a purpose-designed children’s garden in Centennial Park, the circumstances were put in place for the project’s success. At the time there were no such facilities anywhere in New South Wales. The Foundation had already had great success with the Ian Potter Foundation Children’s Garden in Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens, where kids are encouraged to learn through active play.

A balancing bridge entices children through a series of imaginative play experiences.

Image: Brett Boardman

The main idea behind the Ian Potter Children’s Wild Play Garden is to create opportunities for children to reconnect with nature at a time when many have rapidly decreasing access to the outdoors. The Centennial Park Master Plan 2040 established a 6,500-square-metre site for a children’s garden as part of an education precinct just north of the Parklands’ Fly Casting Pond. An ideas competition was held and was won by Aspect Studios. Director of Aspect’s Sydney office Sacha Coles describes the garden as a landscape of water, with a particular focus on how water moves. Centennial Park, where water rises to the surface from artesian sources below, seemed a perfect place to explore this idea.

The water theme provides a narrative spine for the garden as it runs a topographical line down the natural slope. Around this the designers have created a series of characters that inhabit the garden. An endangered ecological community of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub, the bamboo forest, the turtle mounds, the dry creek bed, and the swamp are all characters in a story to discover and explore – as are the structures within. 12,000 plants were deployed in the initial making of the garden, the success of the its composition comes from the design team’s care in setting out the placement of each individual plant, rather than simply applying a series of planting matrices across the plan.

As you enter the garden via its main eastern gate, the sound of water soon becomes apparent. At one of the highest locations the designers have created a “water point”, using large basalt boulders sourced from quarries at Wee Jasper north of Canberra. These Frederick Law Olmsted-like stone markers create a centrepiece for the water narrative, a grotto of sorts from which water bubbles and flows down through the site.

A “water point” surrounded by large basalt boulders creates a centrepiece for the water narrative of the site.

Image: Brett Boardman

In discussion Coles fondly recalls the Rocket Park that was located near the park’s Paddington Gates, named after a climbable red steel rocket ship that once graced the grounds, but is now gone. These Cold War playground features once dotted the world; while loved by many, they have pretty much all disappeared, at least in urban Australia. That idea of a strong feature element of play has been reinterpreted in this garden, with a winding timber treehouse that twists up through the bamboo forest.Eventually the bamboo will be higher than the structure itself, transforming the forest into a three-dimensional maze for scaling, adventuring and racing through.

Another narrative that weaves its way into the design of the garden is that of the longfin eel, which lives in the ponds of Centennial Park. Its shape has been used as inspiration for the low-level serpentine timber sculptural element that might be seats or balance beams depending on age and inclination.

The garden has been designed at child scale, and as soon as you enter the gate there are multiple options to explore. Tunnels through the bamboo, the watercourse bubbling out of the rocks or the fig tree that looks like an old man – you can imagine racing excitedly from one feature to the next, with another two or three appearing in your field of view. Coles explains that the way a child might move through the garden has been prioritized, with every footfall a consideration in arranging the garden’s composition. So too the sounds that come with play – the squish of mud underfoot, the rustle of the leaves or the echo in an underground tunnel – play here is a multi-sensory experience and the spaces of the Wild Play garden are geared to amplify sight, sound, texture and smell.

A bamboo forest replete with tunnels invites children to explore, the sounds of the wind through the leaves creating an immersive, multi-sensory experience.

Image: Brett Boardman

With so much going on in the garden, and so much to learn, it might have been tempting to overload the garden with interpretive signage. Thankfully the project team deliberately looked to the visceral experience of the garden itself to provide the learning, rather than posts with text and pictures. With the spaces refreshingly signage-free, the idea of the garden as a choose-your-own narrative is reinforced.

As the water bubbles away and the kids rumble around, it’s easy to imagine the benevolent, mischievous spirit of Maurice Sendak looking smilingly over the rolling hills of Centennial Park. In the words of King Max: “Let the wild rumpus start!”

Credits

- Project

- Ian Potter Children's Wild Play Garden

- Design practice

- ASPECT Studios

Australia

- Project Team

- Sacha Coles, Kate Luckraft, Louise Pearson, Jane Nalder, Kajsa Bjorne, Thea Harris, Lachlan Bellach

- Client

-

Botanic Gardens and Centennial Parklands

- Consultants

-

Architecture

Sam Crawford Architects

Artist Cave Urban

Landscape contractor Design Landscapes

Playground certifier Play DMC

Project manager RPS Group

Quantity surveyor WT Partnership

Structural and civil engineering Lindsay Dynan Consulting Engineers

Treehouse supplier Fleetwood Urban

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2017

Design, documentation 26 months

Construction 12 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Playgrounds, Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Botanic Gardens and Centennial Parklands

Website Botanic Gardens and Centennial Parklands

Source

Review

Published online: 13 Sep 2018

Words:

David Welsh

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2018