Devastating actions over decades have degraded the systems that support our health and connect us with the “more-than-human world.” This has resulted in many of us becoming estranged from nature to the detriment of our capacities for pro-environmental behaviour and even our quality of life. Beyond the decarbonization imperative, we also need to change cities and suburbs to change how we live. A key part of this change must be the (re)generation of public spaces with abundant nature.

Our gut instinct that “green is good” (and not just for our wellbeing) is being affirmed by a legion of increasingly sophisticated research using sources of “big data” in Australia and beyond, which is not only confirming that we benefit from being in nature but is also revealing how deep the connection between nature and humans extends.

A jogger traverses Prince Alfred Park on an early morning run.

Image: Brett Boardman

Green space and physical and mental health

Our research program, conducted between 2013 and the present, indicates that increasing tree canopy cover from less than 10 percent to 30 percent or more in our local communities could significantly reduce the odds of incident heart diseases and type 2 diabetes. Tree canopy cover is 10 percent or lower in many communities across Australia, such as Blacktown, New South Wales, where rates of diabetes and heart disease are much higher than average.

We have also found that increasing the amount of greenery in our cities might help

to slow cognitive decline, sustain our memory and reduce our risk of developing dementia – however, the type of greenery matters. The results of our 2020 study, for instance, showed that people that had more tree canopy relative to open grass available within a 1.6-kilometre radius tended to have better memory retention, compared to those who had similar quantities of tree canopy and open grass (having access to a higher quantities of open grass relative to tree canopy, however, did not afford similar levels of benefit). Our work also tracked the incidence of dementia over 11 years among 109,688 adults and found that more tree canopy (but not more open grass) lowered the risk of dementia.

Our research has indicated that spending time in natural settings can help to reduce levels of psychological distress and support physical activity. Our 2019 study of adults older than 45 years found, for example, that exposure to 30 percent or more tree canopy compared with less than 10 percent tree canopy was associated with significantly lower odds of incident psychological distress and poor general health. Investments specifically in tree canopy, in other words, may provide much-needed relief from stress and a major boost to our overall health.

Another of our studies completed in 2020 has indicated that green space can even help people to get better sleep. We examined the odds of prevalent and incident insufficient sleep in relation to total green space, tree canopy, open grass and other low-lying vegetation within a 1.6-kilometre radius for participants living in Sydney, Wollongong or Newcastle. Our results showed that the odds of insufficient sleep were lower among participants with access to more total green space and tree canopy; however, there were no significant associations between insufficient sleep and access to open grass or other low-lying vegetation. This could mean that prioritising the restoration and protection of urban tree canopy might help to prevent insufficient sleep in middle-aged and older adults.

Less stress, regular exercise and a decent amount of sleep (typically 7 to 8 hours a night) are all key ingredients for living well longer, and green space is an important contributor of those ingredients.

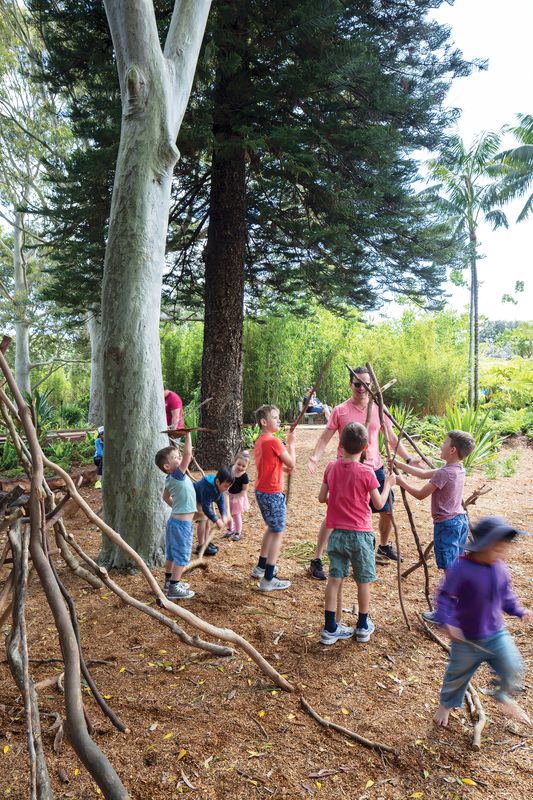

A dense bamboo forest at Ian Potter Children’s Wild Play Garden designed by Aspect Studios at Centennial Park encourages exploration and adventure.

Image: Brett Boardman

Green space and loneliness

But there is another key ingredient. Our recently released research indicates that the positive outcomes outlined earlier could also be attributable to reduced levels of loneliness and that green space may indeed help to reduce loneliness.

Specifically, we found that increasing the amount of public parkland available to Australian adults within a short walk of home from less than 10 percent to 30 percent or more of nearby land-use was associated with a 25 percent reduction in the odds of becoming lonely over four years. For people living alone, which is an important risk factor for loneliness, the odds of becoming lonely dropped by 50 percent after accounting for competing explanations, for instance age, income and education.

This research is significant, as very few effective and scalable interventions for reducing the risk of loneliness are currently known. A common problem is that existing interventions have tended to focus on changing peoples’ behaviour, without consideration being given to changing the places where we actually spend our time and shape what we do.

While urban greening might seem an obvious solution, surprisingly, loneliness has been overlooked in much of the research on the benefits of green space for humans that has been undertaken thus far. Such research, however, is extremely important, given that over 25 percent of Australian adults experience loneliness multiple times a week and a growing number of studies now link loneliness with medical conditions, such as heart disease10 and dementia.11

Hassett Park by Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture introduces a wild aesthetic of grasslands and water to Canberra’s Campbell 5 precinct.

Image: Dianna Snape

How can green space reduce loneliness?

Loneliness isn’t about being alone; rather, it’s a state of feeling alone. A person might feel content and connected on their own, for instance while walking in the hills, or could feel bereft of companionship and camaraderie in a crowded room. Loneliness, therefore, is subjective.

Yes, having good-quality green spaces that are attractive, safe and able to provide opportunities for people to take part in activities that enrich their lives and their communities can undoubtedly play a big part in combating loneliness. This includes bringing people together to share in regular rituals that endow places with collective meanings, such as cheering on the local sports team, volunteering in a park run, walking the dog, picnicking, laughing, and relaxing.

But because ample evidence indicates that views of greenery and spending time in green spaces helps to alleviate stress and anxiety, it may also mean that we – collectively – are more likely to interact in a warm and friendly “pro-social” way together than if we met in less green settings, such as shopping malls. In fact, our recent research has demonstrated greater levels of pro-sociality in relation to quality green space for children and adolescents.13

Meanwhile, with echoes of American naturalist Henry David Thoreau some 167 years on, interviews with residents of a city in the UK indicate that some people may actually seek nature, rather than people, in times of loneliness, for its soothing and non-judgemental support. Urban trees, water, open spaces and views were frequently experienced nature typologies that were internalised as accepting and relational, which helped to encourage and cultivate a stronger sense of self, feelings of escape, and care for the non-human world.

Children craft shelters from branches at the Ian Potter Children’s Wild Play Garden.

Image: Brett Boardman

Net gains in greening for everyone’s health

So, is urban greening a panacea for a healthier, cohesive and prosocial world? If only it were so simple. Disadvantaged communities are often hit the hardest by lack of green space and especially large trees, but many are concerned that greening will worsen housing affordability. Equity, community empowerment and cross-sector policymaking between health, planning, transport and housing must be at the heart of our greening strategies if we are to ensure that the results are cherished and the harms are minimized.

This means empowering communities to take a fuller part in decision-making processes that affect green space provision in their neighbourhoods. A sense of control is a long-established determinant of health and decisions made on greening in which communities perceive they have no meaningful voice can result in feelings of disempowerment, distress and despair.

It should also mean enabling local residents to play valued roles in the upkeep of nearby green spaces. This might involve participating in volunteering programs that align with personal interests and in turn improve health, such as maintaining community gardens and safeguarding wildlife habitats. Studies show gardening can be beneficial for a range of health conditions,while psychological research indicates people tend to have improved wellbeing after doing something good for the environment.

Given that green space offers health and social benefits that standard care typically cannot reach, programs that enable people to spend more time in nature should be actively supported by the health sector. Our research indicates nearly 81 percent of Australian adults would be likely to more frequently visit nature if their doctor told them it would be good for their health. We think our health professionals should consider “prescribing nature,” and we are doing the research to show how this can be done effectively.

To make this a reality, we must establish pathways by which people can proactively connect with and participate in the greening of their neighbourhoods. If we are collectively successful, this may well prove a critical step towards (re)connecting people with their communities, reducing loneliness, improving health, and creating more sustainable futures for everyone.

Source

Practice

Published online: 12 May 2022

Words:

Xiaoqi Feng,

Thomas Astell-Burt

Images:

Brett Boardman,

Dianna Snape

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2022