Digital twins (DT) are increasingly appearing in landscape design projects, from major project briefs through to local council strategies and project promotions. Imbued with the promises of greater efficiencies and adaptable feedback, DTs are often touted as the next generation of data-driven solutions to climatic, environmental, ethical and social decision-making. But can they live up to these claims? While data and technology are increasingly available, when it comes to questions of culture, society and ethics, the quality and depth of that data are highly variable. Further, we have heard many of these claims before: big data, smart cities and BIM have all previously promised to revolutionize how we work and live.

What are digital twins?

A DT is a detailed model (sometimes called a living model) of part of the real world that also includes information about how a product or place performs. So, beyond just the physical shape and size of things, DTs include data about function, operations or behaviours, tracked in real-time. A landscape DT, for example, might include live sensor data about thermal conditions, soil moisture or pedestrian numbers.

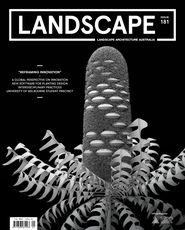

Importantly, data doesn’t just flow into the digital model, it also flows out. This bi-directional flow of information – called “twinning” – means that the model is a highly detailed and accurate twin of the real thing – but also, that the real world can be informed by the analysis or simulations from the DT. Because an ideal DT reflects the details and unique performance of a specific place, it can be used to test or prototype scenarios with place-specific results and feedback. Simulations, optimizations or machine learning can inform real-time decisions based on exactly what is going on, rather than trying to guess or standardize against averages. A great example of this is the smart irrigation project at Sydney’s Bicentennial Park, where soil moisture sensors feed information to a DT model and machine learning adjusts irrigation levels while also monitoring the cooling potential of the park.1

These potentials for greater efficiency, integrated decision-making and optimized performance have technology advocates and Australian local government very excited. The Victorian Government has already committed $37.4 million to Digital Twin Victoria,2 while the New South Wales government has invested in the Spatial Digital Twin project3 and the South Australian government has partnered with MIT to produce a digital twin for Adelaide.4 It is because of investments like these that we are increasingly seeing DT added to landscape projects. The proponents of Melbourne’s Greenline began digitally mapping the north bank of the Birrarung (Yarra River) in early 2023 as the basis for a DT that will support the project delivery and infrastructure.5

DTs are not the first time that data-driven responsive feedback systems have promised radical change for cities and infrastructure. The big data and smart cities movements of the 2000s, followed by the Internet of Things, machine learning and, more recently, artificial intelligence, have all come with claims of unprecedented efficiency and industry overhaul.

At Sydney’s Bicentennial Park, soil sensors feed information to a digital twin model, and machine learning adjusts irrigation levels while monitoring the park’s cooling potential.

Image: Sebastian Pfautsch

Are digital twins just a rebranding of existing data-driven technology?

Regarding the recent history of data-driven hype, the concept of big data first emerged in the 1990s, when the internet and new communications technology started to produce data in never-before-seen quantities. The massiveness of this accelerating data-scape inspired claims of social and economic upheaval. For example, in 2008, Chris Anderson, then editor-in-chief at Wired magazine, wrote an editorial, “The End of Theory,” claiming that big data would replace all tools of decision-making, learning and theory. Similar enthusiasm abounded for smart cities and ideas of autonomous, data-driven technology.6

DTs now offer similar promises, but at an even larger and more interconnected scale. For landscape architecture, this is compelling. Because landscapes are complex, open systems, designing into them demands negotiating how to manage change across often competing environmental, social, economic and political arenas. This is where the idea of twinning is very appealing. Because DTs are framed as exact replicas of physical space and able to capture everything, no plant, animal or community is left behind. More than just replicating environmental performance, the potential comprehensiveness of a DT can serve to align pragmatic issues with the nuances of social and cultural influence.7

However, these kinds of claims assume that information itself is neutral or objective and can be cleanly synthesized into a precise replica of a real-life environment. This creates a kind of paradox in data-driven modelling because even highly detailed models or twins simply cannot account for all things at once. While physical traits are more easily capturable, conditions of culture, society and ethics are much harder to represent, and the quality and depth of these types of data are highly variable – if these data are even available. The creation of any data set or flow is dependent on human-led decision-making where there is a necessary scoping and critical questioning which begins at the very first moment of deciding where to capture data from. This means that even the most detailed DT is programmed by humans with pre-existing values and world views that set up what a model includes and excludes. We have already seen this discussion in relation to smart cities and big data. Isolated, data-driven decision-making has been called out for disciplinary bias toward particular ways of seeing, lack of social nuance and restricted cultural diversity.8

How innovative are digital twins for landscape architecture?

Historically, landscape architecture has not felt the data and digital revolution nearly as much as other disciplines and industries. From digital simulations to the uptake of BIM, we have often been late to the table when it comes to digital innovation.9 There are a host of reasons for this, but in part it is because of the difficulty of optimizing or reducing large, complex and dynamic landscape systems.

The responsive flow of information through twinning suggests that this advance represents a big step toward overcoming this obstacle. However, not all digital models described as DTs deliver on the promise of detail, comprehensiveness or responsiveness. A 3D model embedded with some sensor data doesn’t come near the innovation of reactive bi-directional data testing and response. Only a few DTs integrate the spheres of environmental, social and economic performance, let alone address ethical issues. At this stage, at least, that kind of DT is more theory than reality.

For now, the DT hype is warranted in the most practical of applications like infrastructure systems, transport and management. For landscape architecture, there is innovation to be found in responding to local climate conditions and in reactive maintenance. However, to maximize innovation, investment in DTs needs to be in more than the technology alone. Rather than assuming that just having data is enough to overcome complex environmental and social challenges, we need to critically examine and expand our processes and methods of data capture and synthesis, interrogate which data we capture and why we are capturing it, and consider the ethics of information inclusion and exclusion that inform our digital models. Unlocking innovation is about the growing capability of the technological, but it is also about connecting the ethical dimensions of governance and design into how we address environmental performance, social nuance and cultural diversity to create resilient, beautiful and inclusive landscapes.

1. Sebastian Pfautsch, “Designing for coolth,” Landscape Australia, 23 May 2022, landscapeaustralia.com/articles/designing-for-coolth.

2. State Government of Victoria, Digital Twin Victoria, 2022, land.vic.gov.au/maps-and-spatial/digital-twin-victoria.

3. New South Wales Government, NSW Spatial Digital Twin, 2023, spatial.nsw.gov.au/digital_twin

4. Government of South Australia, Department of Trade and Investment, “Adelaide aims high with AI initiative,” 20 May 2021, Department of Trade and Investment, dti.sa.gov.au/articles/adelaide-aims-high-with-ai-initiative.

5. City of Melbourne, Greenline Project, 2023, melbourne.vic.gov.au/building-and-development/shaping-the-city/city-projects/Pages/greenline-project.aspx.

6. Anthony Townsend, Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2013).

7. Soheil Sabri, Stephan Winter and Abbas Rajabifard, “Creating digital twins to save our cities,” 2 March 2023, Pursuit, pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/creating-digital-twins-to-save-our-cities.

8. Kristin Asdal, “Enacting things through numbers: Taking nature into account/ing,” Geoforum, vol. 39, no. 1, January 2008, 123–132; Jennifer Gabrys, Citizens of Worlds (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2022); Sun-ha Hong, Technologies of Speculation: The Limits of Knowledge in a Data-driven Society (New York: NYU Press, 2020).

9. Jela Ivankovic-Waters, “Embracing the innovation debate,” 5 July 2022, Landscape Australia, landscapeaustralia.com/articles/embracing-the-innovation-debate.

Source

Practice

Published online: 8 Feb 2024

Words:

Wendy Walls

Images:

Digital Twin Victoria,

Sebastian Pfautsch

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2024