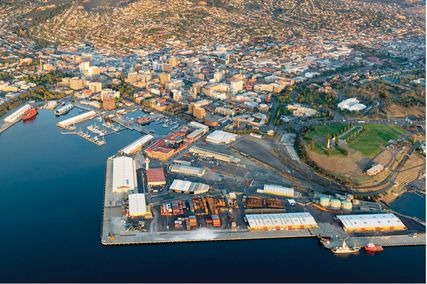

Philanthrocapitalism has come to public parks. In Tulsa, Oklahoma, a local billionaire is making a $465 million park in an effort to give the city a green heart, like other great cities do. The billionaire is doing it in a way the state or city never could, crippled as they are by the public’s ingrained avoidance of providing any tax base. The park’s dollar amount is staggering. Half a billion. The democratic ideal of social integration is a key goal of Gathering Place. The project currently consists of 27 hectares of sports and wetland and lake and towering rockscapes and planned skateboard park and dining strip, all assured with a $100 million endowment for maintenance and programming. Two massive land bridges span a highway to bring the park to the locally maligned Arkansas River. And children from all over the city are bussing in to play at the Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates-designed supersized two-hectare playground that has something for every age group: a bespoke circus packed with props (that at the time of my visit was bursting with kids), giant-like figures crafted from immense tree branches, a huge prehistoric billfish sculpture and water engineering. Child development professionals staff the area designated for the youngest children. It’s remarkable.

Gathering Place in Tulsa, Oklahoma by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates.

Image: Elizabeth Felicella

Is this the best way to spend half a billion dollars? I can’t say I know Tulsa well enough, or the politics of ultraconservative Oklahoma. Would investing a million dollars in 465 of the many in-disrepair local parks in the poorer parts of the city make for greater change than this cross-town dazzling extravaganza? Nor do I know the environmental and human costs incurred in the making of that half a billion dollars eventually destined for philanthropy. Which brings me to the point: how do we reconcile our ambitions to protect, sustain and restore the environment – a position enshrined in the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ charter1 – with the scale of actions required in the face of impending ecological collapse, and with our constrained position as landscape architects in the scheme of things?

We have come a long way in the fifty years since the publication of Ian McHarg’s Design with Nature (1969), which helped set modern landscape architecture on its rightfully environmental course. But what we tend to do now is design with nature for humans. Our projects are almost universally measured by reference to their social and aesthetic qualities, on how they meet political needs, and only rarely do we attempt to assess any net benefits they might provide to nature. Even in projects such as New York’s High Line, we don’t weigh the biodiversity that comes after with the biodiversity that was present before. Now we have to design for nature.

Down off Staten Island, New York, is a great example of designing for nature that involves fundamental research into an adaptive infrastructure that may be able to move with sea level rise and go some way toward protecting the coast. Oysters – part of one of the world’s most endangered marine ecosystems – are ecosystem engineers, catalysing beneficial regeneration across many species. A project to build a four-kilometre living breakwater of oysters off Staten Island received $60 million funding from the US-based Rebuild By Design competition, as part of a post Hurricane Katrina wake-up. The project involves landscape architecture practice Scape fitting recreational development and human amenity in behind the bioengineering. Doing nature a service is often not glamorous. And adding people to those designs without self-defeating compromise is the hard part.

On Chicago’s South Side, Henry Palmisano Park is a standout example of an ecologically oriented park in an old quarry and landfill. In the eleven-hectare site, Site Design Group and D.I.R.T. studio2 have made a prairie sloping down to a lake. It feels wild, with its recycled slabs of concrete and cliff face, and a stream managing all water on site. A lot of the park is fenced off, putting humans in their place. Fishing is promoted – catch and release – a little cruel, but it brings awareness of the life within. The park gets burnt – now that’s engagement with nature – and wildfire a boon to the prairie species. There are lookouts offering rare views of the city skyline, places to lie on lawn and jogging and walking tracks where, against the slope, you are at eye-height with magnificent floral displays. There’s a lot to engage with: the human experience is rich and orchestrated and it’s all made possible by the more conventional park adjacent, with its community facilities and playground. The two work together hand-in-hand – and it’s true we won’t solve the ecological crisis without solving the social crisis.

A stream rushes over recycled concrete slabs into the lake at Henry Palmisano Park.

Image: Adrian Marshall

At Henry Palmisano Park, a steel walkway leads into the sloping site, offering views of the exposed quarry cliff face.

Image: Robert Sit, Site Design Group.

There’s a level of humility present in Washington Avenue Pier in Philadelphia, designed for the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation (DRWC) by Applied Ecological Services, as part of a twelve-hectare wetlands development along the very-working Delaware riverfront. It’s a small project in an unfashionable area. A path leads you beside an old car park, with weeds growing through the cracks though – hold-on – they are native weeds, that is to say not weeds, but a palette of plants. It’s an amusing move. The pier itself has been stabilized and the thick vegetation running out into the Delaware River – dense undergrowth beneath substantial canopy – is a mix of natives and the opportunistic species that have made the pier their home for many years. A rough track runs through it. Down on a small newly constructed beach two men are fishing. The air is filled with birds and insects. Five hundred metres along the shore, opposite a Walmart, another pier has been rejuvenated by the DRWC into a rather less successful, more “public” public space.

Washington Avenue Pier provides habitat for diverse wildlife including migratory songbirds and waterfowl.

Image: courtesy Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

Native flora and weeds thriving at the restored Washington Avenue Pier along the Delaware River.

Image: James Abbott

Beyond opportunities like these, what are we to do? We certainly have to foreground the bigger picture. Branding, ego, money and making public space that shouts that it is for the people all tend to lead to poor ecological outcomes. Positioning nature as a tool for achieving human amenity is not a useful mindset. Playgrounds, integrated public art, mastery of the ground plane – it’s all what we learnt as we grew up as a profession, as we discovered and claimed our reach. To mature as a profession we must meet the challenges of the future. In an excellent and provocative article, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Ian McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology and former domestic policy advisor to the Obama administration, Billy Fleming, makes a strong case for political action, for embracing the scale of change required of the landscape architectural profession and for actively engaging in fundamental institutional reform and the biggest idea of the century – the Green New Deal.3 Without doubt, we must do something to get out from beneath the burden of insufficient action accompanying practice. Without such change, we will position our profession as part of the problem, not part of the solution.

1. AILA, A charter for Australian landscape architects, 2016, https://www.aila.org.au/imis_prod/documents/AILA/Governance/AILA CHARTER 2016.pdf. Accessed 3 December 2019

2. The design schematic for Henry Palmisano Park was completed by D.I.R.T studio with implementation by Site Design Group.

3. Billy Fleming, “Design and the Green New Deal,”Places Journal, April, 2019, https://placesjournal.org/article/design-and-the-green-new-deal/. Accessed 3 December 2019

Source

Practice

Published online: 26 Apr 2020

Words:

Adrian Marshall

Images:

Adrian Marshall,

Elizabeth Felicella,

James Abbott,

Robert Sit, Site Design Group.,

Scott Shigley for Site Design Group.,

Scott Shigley for site design group, ltd. (site),

courtesy Delaware River Waterfront Corporation

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020