Whenever a cyclone makes landfall it is followed by a familiar sequence. People affected are persistent about the damage, the costs and the need for insurers to act now to compensate their losses; the state and federal governments extensively discuss who is to blame; and billions of dollars are spent o n relocating people and repairing the damage – a state-level levy may even be necessary to pay for all the extra costs . In the wake of 2017’s Cyclone Debbie, the Queensland state and federal budgets are expected to take a $1.5 billion hit, with the overall damage bill to infrastructure predicted to reach $2 billion. This is not to mention the devastation experienced by families and entire communities due to loss of lives and livelihoods.

We know the impacts that cyclones can have and we know where they tend to occur, yet our cities are not designed to cope with these types of events. Cyclones bring, for a relatively short time, huge gusty winds – these are inconvenient but have proven not too damaging. The greatest risk comes from the storm surge and rainfall that accompany the cyclone – both bring a huge amount of water, which needs to find a way out of our living environment.

What can we do to minimize the impact of cyclones – and the accompanying rainfall and/or storm surges – so that they do not greatly disrupt life? The answer is in design.

Rethinking coastal design

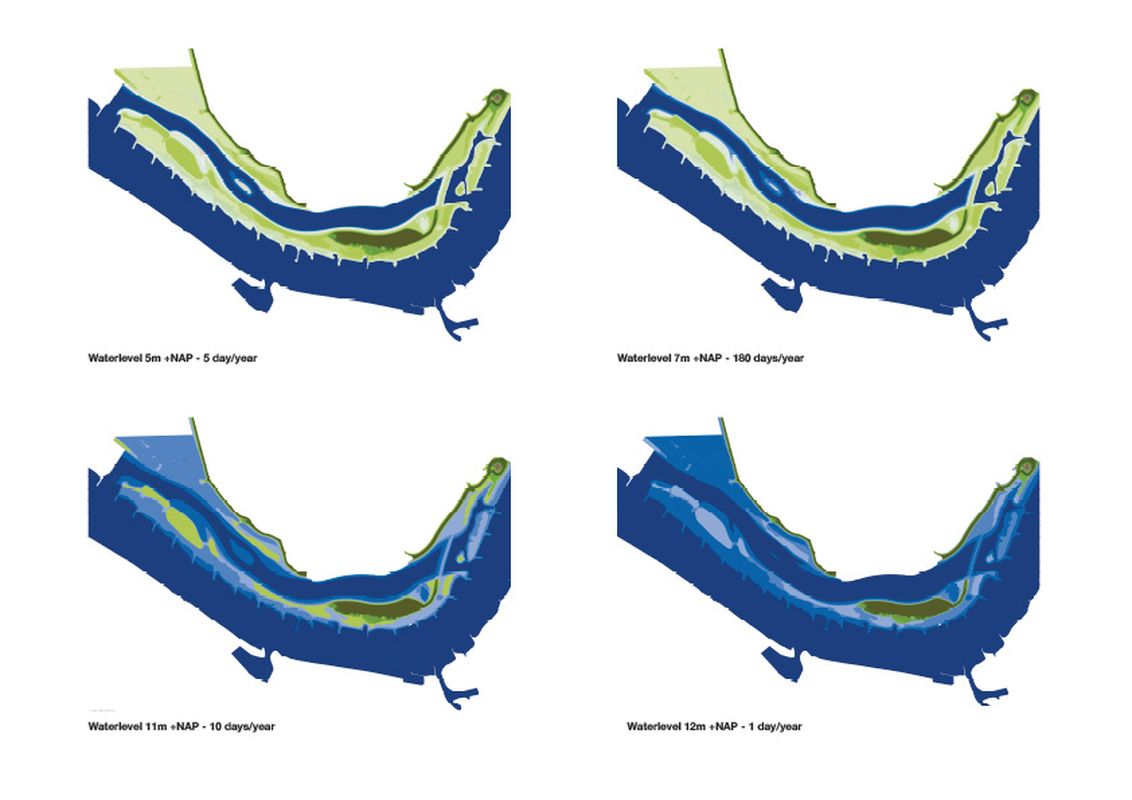

Building towns and cities that are stronger against cyclones starts with coastal design. In Australia we are used to building dams and coastal protection to cope with storm surges that happen once in a hundred years. For comparison, the protection standards in the low-lying Netherlands are designed to protect the country against a once-in- ten-thousand-years flood. But nature has proven to be stronger than our artificial constructs can handle.

An alternative design approach is to rely on the natural coastal processes of land forming, such as reefs, islands, mangroves, beaches and dunes. Humans can help the formation of these natural protectors by providing the triggers for them to emerge.

As an example, when we put sand out from the coastline, the currents and waves transport the sand toward the coast and over time it builds up new and larger beaches. This has been done along the Dutch coast and is known as a sand engine. In this process, nature builds new beaches and dunes to form a much stronger system than humans ever could, preventing coasts, beaches and real estate from being washed away. This requires design thinking, insights into the resilience of the coastal system and an understanding of the natural forces at play.

Redesigning our river basins

We also need to redesign our river basins. Instead of them discharging water as quickly as possible, flooding town squares and streets, we need to increase the storing capacity within the river basin. The watershed should be central in our design resolutions.

In periods with heavy rainfall, the rainwater captured within one watershed should stay there for as long as possible. Currently, water is often captured in large dams and lakes, but once these are full, the excess water needs to be released. Often there is too much rainwater to be released, especially during disruptive events of longer periods with heavy rain, and this water uses creeks and rivers to find its way – meanwhile flooding towns, landscapes and cities.

The flood-control channel in Nijmegen has created an ephemeral island that forms part of a new river park.

Image: Siebe Swart

River basins need to be designed so that they have extra capacity to store water for several days. This can be achieved through increased tree cover, as the trees take up water and the leaves hinder the rain from reaching the ground. Areas for overflows should be created along rivers. The good old billabong has left the scene, but should be revalued as the capturer of water. This could easily be achieved if the river was allowed to meander again – with every corner and every turn, the river slows down the water. This set of measures requires understanding the river system as a whole, rather than seeing it as a discharge channel with a floodplain alongside it.

How should we redesign our towns?

Urban design should be used to reconsider the way we design our towns. Most built-up areas do not have the capacity to “welcome” a large amount of water and with cyclones we are talking about lots of water, not the average shower or two. Until a cyclone has eased, the enormous amounts of water need to be stored for a couple of days in built-up areas. This requires going beyond water-sensitive urban design. Despite its benefits in many developments, when the going gets tough it is just not enough. In times of severe weather events, towns need to have additional spaces to store all this water. The general rule here is to store every raindrop for as long as possible where it falls.

In Rotterdam, Water Square Benthemplein by De Urbanisten stores water temporarily after heavy rain.

Image: De Urbanisten

Even in most rural towns the “concrete jungle” is spreading. The communal square, paved front gardens, increased road space – it all creates towns that become less receptive to large amounts of rainwater. Public spaces, rooftops and infrastructure in these towns should be redesigned as part of any development the town undergoes.

What could be done to let our towns operate like a sponge? This would mean that the town absorbs huge amounts of water and releases it slowly to creek and river systems after the rain has gone. The green spaces and water spaces would not only play an important role during and just after a cyclone, they would also add quality to people’s immediate living environment.

A range of design strategies can be implemented to achieve this, including something as simple as creating rooftop storage basins of thirty centimetres in height (or the equivalent of a group of buckets).

Other strategies include designing larger green spaces connected in a natural grid, increasing the capacity of these green systems by adding eco-zones and wetlands, and redesigning river and creek edges. This includes removing the concrete basins from every creek in the city.

“Green creeks” that can operate as a bypass of the main creek can also be created – in dry periods these green spaces can be used for leisure, agriculture or sports activities, but can be opened for excess water as soon as it starts raining or the storm surge comes through.

Water squares can be created to store water temporarily and can otherwise be used as a playground or sporting facility. Larger carparks, ovals or football pitches can be designed for use as temporary storage. Through placement of a little dam of thirty to forty centimetres around a parking area, a whole lot of water can be stored and released later.

Street profiles can be redesigned to introduce green and water zones. This includes the redesign of impervious, sealed spaces to turn them into areas where the water can infiltrate the soil (using permeable materials).

These measures, when used together, can prevent a town from flooding. While the measures are relatively easy to realize, good design is needed to ensure that they are used to create quality public spaces. (Re)design of our coastlines, river basins and towns is vital and needs to integrate space for water with other urban purposes to establish a safe, appreciated and beautiful urban environment.

Source

Practice

Published online: 20 Nov 2017

Words:

Rob Roggema

Images:

De Urbanisten,

H+N+S Landscape Architects,

Ossip van Duivenbode,

Siebe Swart,

Tom Papworth

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2017