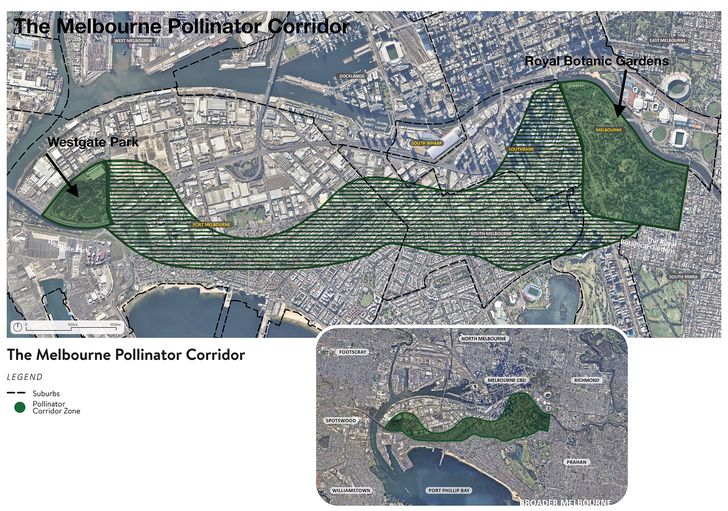

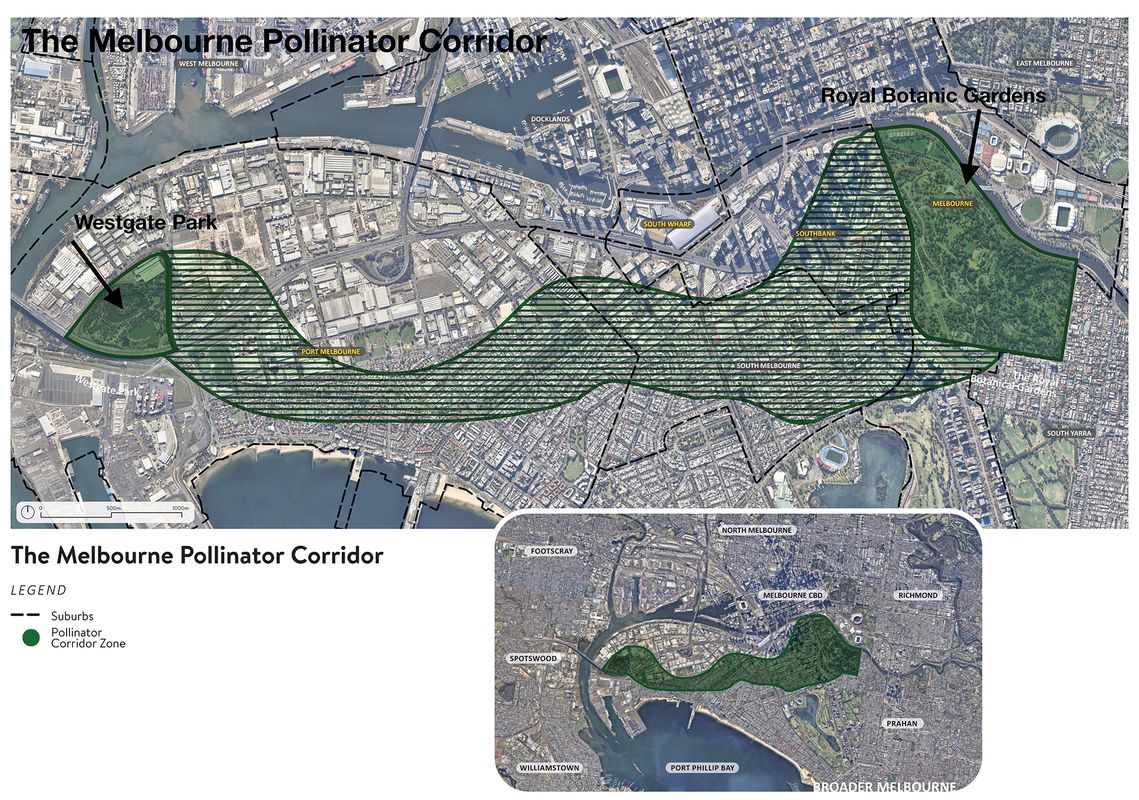

The Melbourne Pollinator Corridor (MPC) is a large-scale landscape project undertaken by a non-landscape architect. The eight-kilometre wildlife corridor links Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens and Westgate Park via a growing number of small, community-led street gardens. Its founder, Emma Cutting, says it is held together by the transformative effects of care. The project has established interconnections across ecology and community in South Melbourne and rewritten the rules of streetscape design in the local council area, demonstrating levels of community investment and empowerment not typically achieved through landscape architecture projects. And it all started small.

The MPC was initiated in 2019 with a prototype garden. It currently comprises 20 gardens; Cutting aims to realize 200 by the end of 2024 and has distributed 40 “Corridor Kits” to support this process. The larger initiative that the MPC belongs to – the Heart Gardening Project, which is also led by Cutting – has directly created over 80 gardens and comprises over 8,000 plants. “[The project] joyfully connects humans to humans, humans to nature and nature to nature through street gardening,” Cutting says. The gardens occupy a range of site types, including council land (nature strips, which are the maintenance responsibility of the adjacent owner-occupier), government land (social housing landscapes) and privately owned public land (carparks).

Seeing our medium and practice through the eyes of someone beyond our discipline is revelatory. All aspects of the project take unfamiliar forms – design processes, project timeframes, understandings of “site” and approaches to documentation, construction and maintenance – and reimagined, they achieve radically different ends. As an unorthodox landscape project, the MPC provides lessons for our profession around open-ended design methodologies, the building and sharing of design knowledge with non-designers, the importance of prototypes and the generation of meaningful, caring relationships with public landscapes.

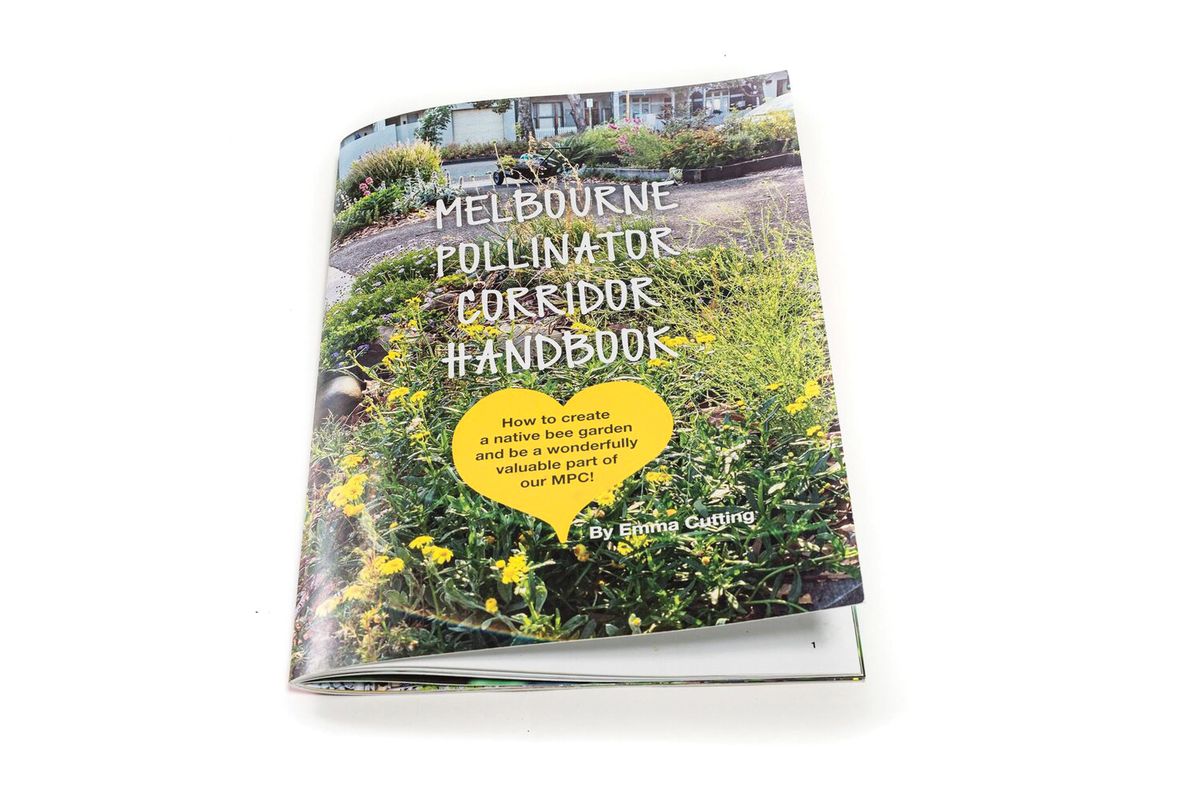

Emma Cutting, who founded the corridor project, has created a detailed yet approachable handbook to encourage new participants.

Image: Emma Cutting and Lee Burgemeestre

Designing a shared, open-ended process

The MPC comprises small street gardens designed, constructed, and maintained by adjacent residents; the gardens operate collectively as a corridor, which has growing scope. This distributed but coordinated project model has required an approach that is open and open-ended – rather than a design, the project provides common but loose frameworks, which define collective project scope at the large scale (the corridor) and guide individual design work at the small scale (the garden).

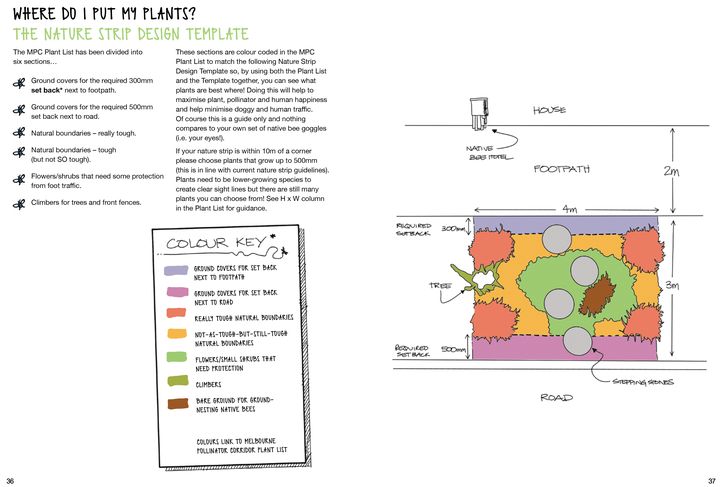

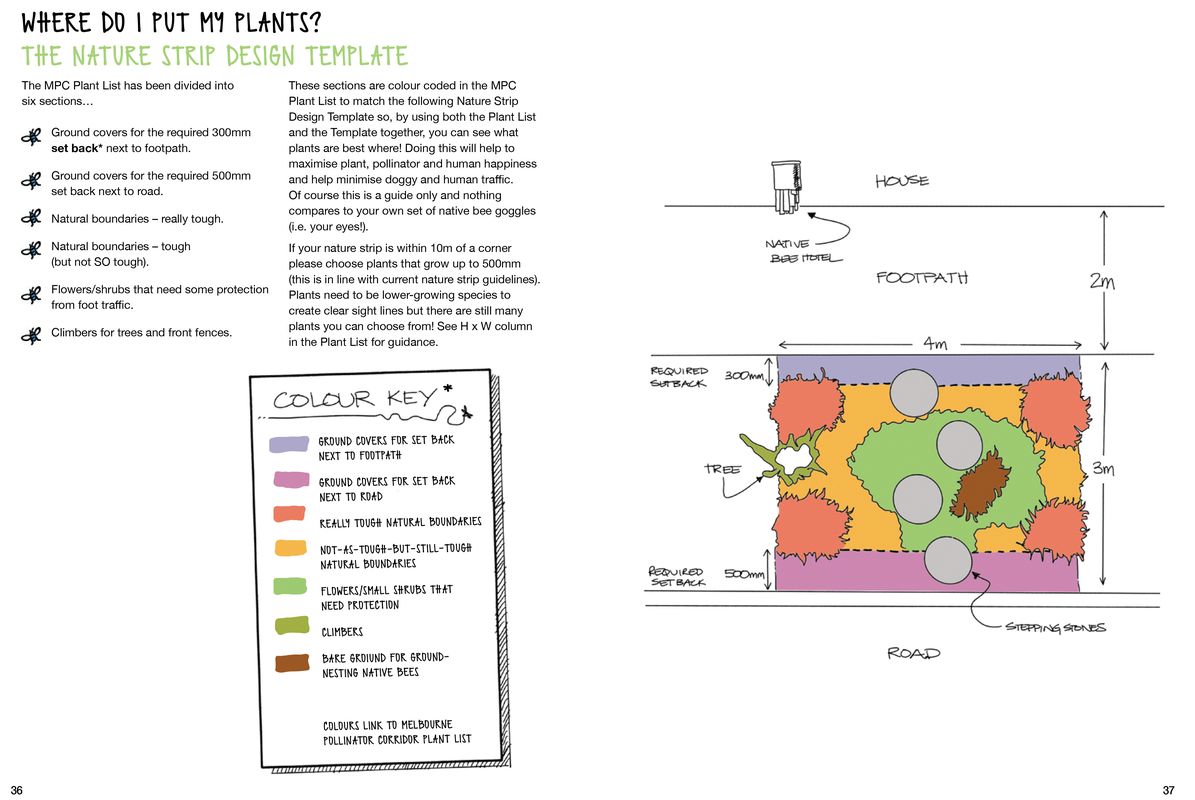

Rather than a masterplan, the corridor is communicated through a diagrammatic drawing that clearly translates the project’s ambition – the corridor’s gestural, indicative plan provides a structure around which work can be coordinated while supporting the greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts vision to which participants are contributing. At the scale of the garden, Cutting has prepared design templates, which offer guidance while inviting interpretation, allowing for the type of “tailored participation” needed to build and sustain the garden. “The project is about knowing that everyone will approach their garden in a different way, supporting people to learn, and getting enough information out there for people to go, ‘That’s what it is, and we want to be a part of that,’” Cutting says. “[It’s about] being open enough to interpretation [so] that people can tailor their version of participation.” Overall, the project coheres because its gardens share a common set of rules and values, but in a way that can shift scope and form as the project evolves.

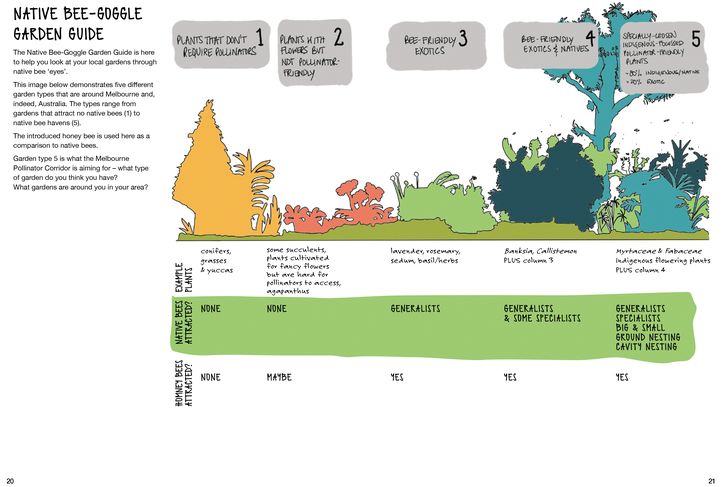

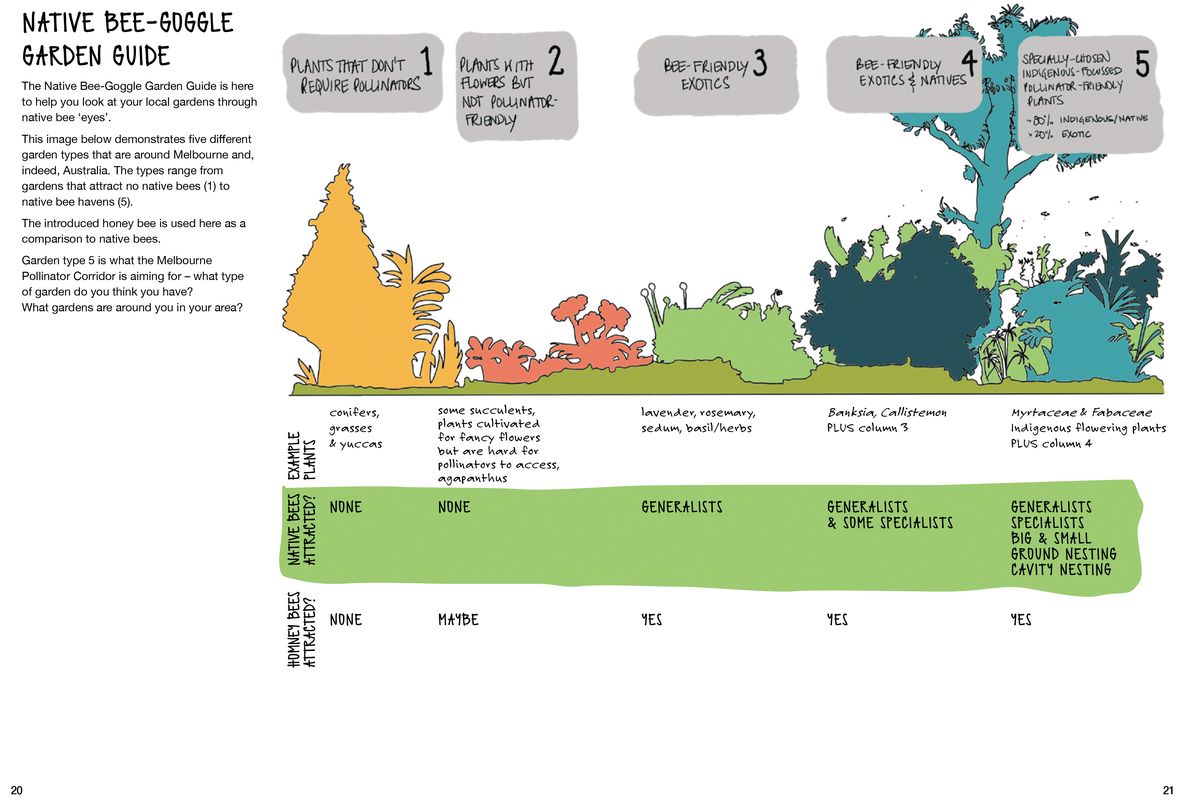

The handbook’s “native bee goggle garden guide” evaluates gardens through the habitat suitability of their groundcover and shrub layers.

Image: Matt Kurowski and Lee Burgemeestre

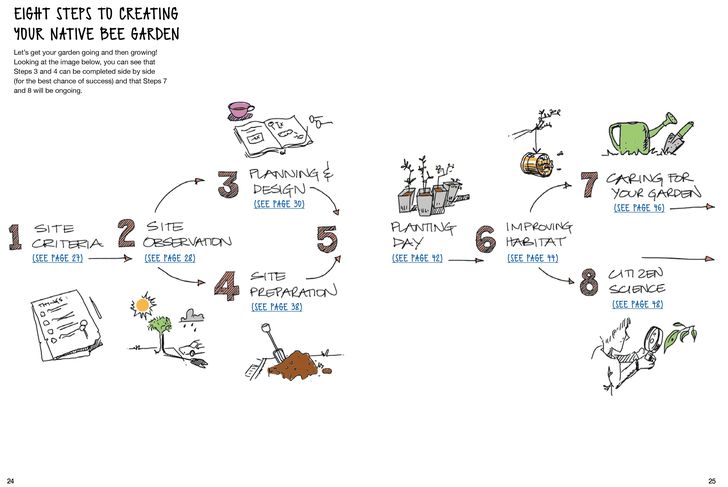

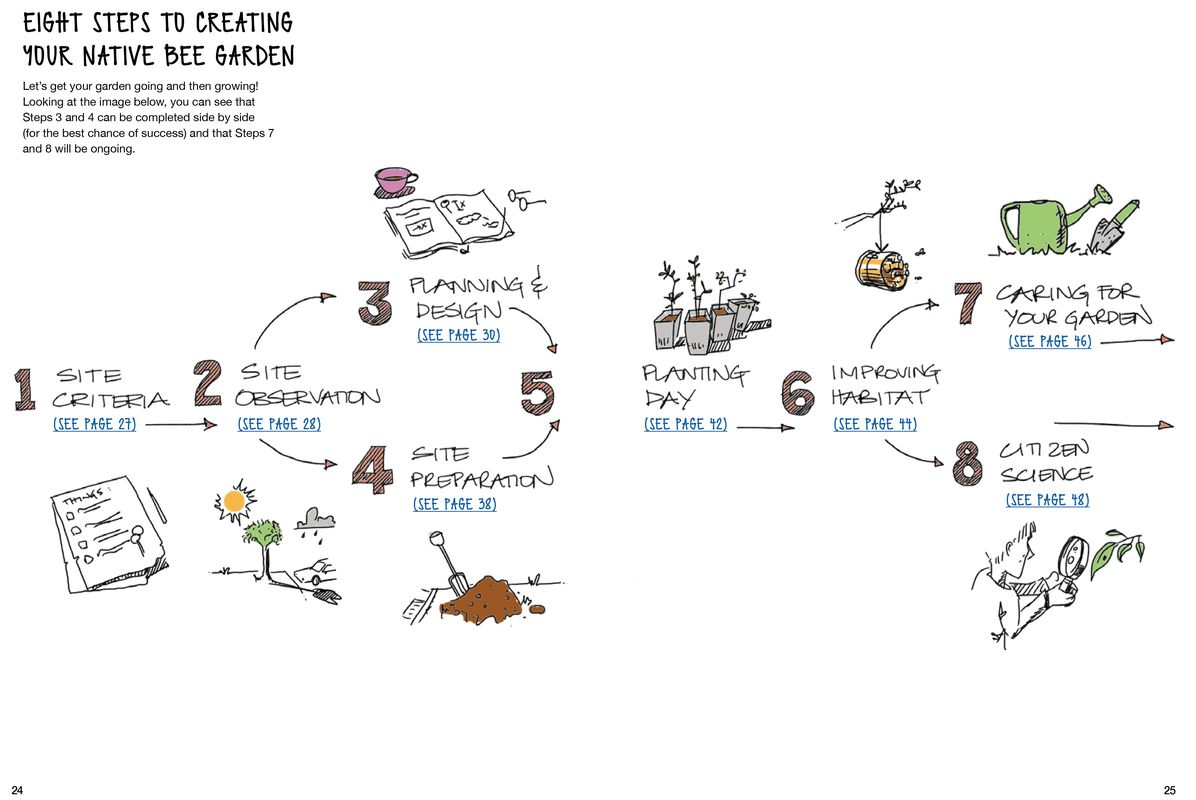

Cutting’s storybook-like illustrations demonstrate an achievable eight-step process for creating and maintaining corridor gardens.

Image: Matt Kurowski and Lee Burgemeestre

New modes of documentation, new ways of seeing the built environment

Key to the project’s community-led approach are welcoming and accessible modes of documentation that translate design and technical knowledge to non-designers. Project documentation takes the form of the Melbourne Pollinator Corridor Handbook, which was authored by Cutting as “the handbook I wish I had been given years ago when I first started this street gardening-urban-biodiversity journey.” The handbook reads as a vision document, a field guide, a documentation set and a technical specification.

The handbook draws a series of ties across different fields of knowledge to generate a comprehensive guide for a non-designer or gardener approaching the project, meeting the gap Cutting observed in the existing literature. To prepare the book, Cutting consulted with over 30 scientists and specialists, including conservation scientists, entomologists, native bee experts, land care groups, botanists, ecologists, landscape architects and planners. The documentation synthesizes and translates this information into an achievable, eight-step process for planning, designing, constructing and maintaining. Appendices include extensive plant lists, supplier information and guidance around regulatory barriers. Despite the complexity of the information it communicates, the handbook uses storybook-like tones and illustrations to communicate approachability and support.

The documentation modes developed in the handbook also provoke shifts in ways of observing relationships across the built environment – between self and nature, self and community, public and private, micro and macro – and support new connections to take form. In Cutting’s words, “Street gardening asks people to rethink the public space outside their home with a mindset that’s determined and generous and community minded. And that involves immersion and observation. It’s seeing the street through an ecological lens and your garden as a smaller, immediate little system. And then seeing the social version of that. And the overlap between ecology and community.” This shift is supported by visualizations that envision the world through another species’ eyes. The handbook’s “native bee goggle garden guide,” for instance, evaluates a series of gardens through the habitat suitability of their groundcover and shrub layers, while Cutting’s macrophotography practice, which features throughout the book, invites us into another scale while revealing the beauty of pollinators. Ongoing observation, such as coordinated monitoring of plant health and pollinator counts, reinforces the attunement to the relationships between species and community that sustain the project.

The project sets new precedents for streetscape guidelines and encourages community advocacy around the public realm.

Image: Matt Kurowski and Lee Burgemeestre

The importance of prototyping

The project started with a prototype, and Cutting acknowledges the importance of starting small and proving the model before gradually upscaling. A prototype, she argues, grounds the vision – but, more importantly, it inspires imagination, supporting a different outlook on what is possible.

In Cutting’s words, “Humans have amazing imaginations, but we arguably don’t use them as much as we could. If I had said, ‘We’re on this council campaign, this is what we can do, we haven’t done it yet, but can you imagine all these beautiful gardens on these nature strips?’ I know people wouldn’t have been as willing to come on board if they hadn’t seen or experienced the idea realized. The project requires the ability to look at things completely differently, which people can do only when you have proven it can happen and they walk past it every day. The more that people can see that something can be done to change our world, the more their outlook changes on how much power we actually have as humans.”

Starting small makes participation in an ambitious project seem achievable; makes one’s contribution to it tangible; establishes a beautiful, socially scaled space that hosts conversation; and is a thriving advertisement for the outcomes the project can achieve.

Small streetscape gardens that are designed, constructed and maintained by adjacent residents form a substantial pollinator-friendly corridor.

Image: Emma Cutting and Emma Jackson

Cultivating care

Care is key to the success of any garden and, as the Handbook’s chapter on maintenance notes, “is the most important part of your gardening journey.” The MPC is unique in that it has built a thriving relationship of care between a community and a large-scale public landscape. This force of collectivized care has not only sustained the project’s maintenance and monitoring, it has also precipitated systemic change across the project’s local built environment.

In 2022, Cutting and the MPC community successfully advocated for a change to local legislation around nature strip guidelines to protect street gardening from the threat of non-compliance. This campaign included an 84-page evidence-based document by Cutting, a 5,935-signature petition, 20 letters of support from experts, support from three levels of government and over 600 individual submissions from residents. A concurrent crowdfunding campaign raised more than $30,000 for the project, which kept approximately 360 acres of local nature strips open to gardening and set a significant precedent for community advocacy around the public realm.

“Care is usually focused on the private realm, but this project brings it out, shares it and contributes it to something bigger,” Cutting says. “Street gardening is not necessarily about the garden. It’s about care. When you care, and the care overlaps with someone else’s care, and then theirs overlaps with someone else’s, you get a power on many levels. And that’s the power of street gardening.”

Source

Practice

Published online: 8 Nov 2023

Words:

Jen Lynch

Images:

Emma Cutting,

Emma Cutting and Emma Jackson,

Emma Cutting and Lee Burgemeestre,

Matt Kurowski and Lee Burgemeestre

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2023