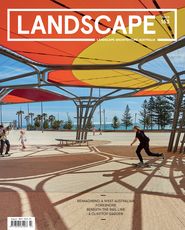

Suburbs in Sydney come burdened with associations. Vaucluse, in Sydney’s east, is no exception. Poised at the entrance to Sydney Harbour, and edged on two sides by clifftops boasting jaw-dropping views of either the Tasman Sea or the harbour, Vaucluse is a place perhaps more renowned for its trophy homes than for sensitive, introspective spaces such as gardens. Visiting a garden designed by Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture (JILA) and perched on these very eastern clifftops, however, I’m refreshed by what I find.

Prior to JILA’s engagement by the current owner, both the shape of the house and the physical dimensions of the garden had been predetermined, with the house designed by the late Australian architect Paul Pholeros. The garden’s design is an exercise in contextualizing the house, grounding and orienting its relationship to an extraordinary position. In relation to the landscape the house acts as a windbreak, separating the exposed, east-facing rear yard from the sun-drenched west-facing front. With the house and natural pool completed prior to engagement, Jane Irwin, principal of JILA, describes the design of the garden spaces as an exercise in stitching.

At the front of the house, the tired tropes of the suburban front yard are unpicked. Defying a stark boundary between the private and public realms, the garden spills streetward. Scented geraniums colonize the footpath, releasing perfume with the contact of passers-by, and in their rapid growth hold space while slower-growing plants, including correa and westringia cultivars, establish themselves, acting as subtle reminders of the site’s lost ecology. In place of the usual uninspiring and thirsty lawn, clumps of fragrant herbs and edible groundcovers – oregano and thyme matted with native violet and kidney weed – create a soft, wild carpet underfoot. Here, the processes of succession have been invited in to transform a spatial typology often expected to provide a static frame to the street.

The house’s front garden spills toward the street, blurring the boundaries between the public and private realms; planting references the site’s former ecology.

Image: Dianna Snape

JILA has designed both front and rear spaces to perform – to provide. The house’s owner mentions that neighbours and walkers en route to the area’s nearby clifftop parklands often slow to admire the garden, commenting on its abundant planting. This is hardly surprising. In contrast to the gardens of neighbouring houses, (which are often bare and denuded for fear of obscuring precious views), this landscape is full, generous and alive. Facing the street, small trees work both as screens and producers, with guava and citrus trees nudging the edges of the space and local native species jumping the boundary. Banksias supply nectar and shelter for local wildlife and a coastal tea tree offers dappled shade and the promise of a future gnarled and greyed trunk. I ask Irwin a dull question about maintenance, and the question is reshaped in her answer, becoming an anecdote about how the garden teaches, with decisions about pruning, removal and maintenance weighed against the course the garden itself wants to take – a process of watching and learning.

As the three of us – writer, owner and designer – sit in the house’s rear space, partially blinded by the morning light blinking off the Tasman Sea, the owner claims the garden is, despite appearances, “not about the view.” This is at least partially true. Despite its ocean outlook, the design of the house’s rear landscape shuns the usual strategies of view-framing, tumbling downward from a square of lawn toward exposed rock faces that reference and reinforce – through form and materiality – the site’s clifftop location. The garden’s current form reflects a “starting point” planting plan (from which planting has continued to change and evolve), with individual specimens selected and positioned according to the fall of the site. Space has been defined by an artful placing of stone. Rock orchids sprout adjacent to a stair at the end of the house’s natural pool, while commontussock-grass captures the morning light, bending romantically in the wind.

A moving garden: from the designer’s initial plan, planting has been encouraged to adapt and evolve in response to the site’s dynamic conditions.

Image: Dianna Snape

The intimate scale of the house’s rear garden counterbalances the immense drama of the ocean panorama.

Image: Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture

Sandstone rough backs – waste material sourced from a Sydney stoneyard – bridge the garden’s spaces, nestling into the site in a balancing act that melds the existing with the conceived. At the garden’s base, a trickling rill gently filters water through aquatic plantings that is later fed back into the pool. The folded landscape echoes the Japanese influence in the house’s architecture, filtered through a uniquely Australian lens.

This corner of the rear garden also functions as a clever counterpoint to the site’s sublime view, which, framed by the floor-to-ceiling glazing of the house’s rear, requires little embellishment. In contrast to the immense expanse of ocean that unfolds behind the building, the garden exists at a micro scale, rewarding more intimate forms of engagement. A sunken seating area turns inward, using stone recycled on site to anchor sitters in place. This most intense part of the garden also subverts expectations of usability, with the owner recalling that her most enjoyable moments have been watching her grandchildren playing, not on the lawn overlooking the ocean, but hopping between the stones, spotting lizards.

Rather than framing ocean views, the design directs attention inwards, highlighting the clifftop’s unique geology and form through exposed rock faces.

Image: Dianna Snape

Our discussion creates curiosity about the brief. An initial impetus was to live in the landscape, not just admire the view – a preference for experience over appearance. This has presented a refreshing challenge for JILA. The result is a garden that highlights natural phenomenon and the elemental over the pictorial, something we experienced that day as swallows skimmed the natural pool and a visiting kookaburra inelegantly snacked on a blue-tongued lizard.

For landscape architects, the opportunity to work at the garden scale is often dismissed in favour of grander public gestures. Noting this, I ask Irwin for her thoughts on the benefits of working at this smaller scale. Her answer centres on the chance to establish and maintain a relationship based on observation, consultation, continuity and care – a compelling argument for maintaining a critical voice in shaping gardens as intimate places in which we live.

Plant list (indicative) – Front and side gardens

Ajuga reptans (bugle), Banksia integrifolia (coast banksia), Banksia robur (swamp banksia), Begonia scharfii (elephant ear begonia), bromeliads, Citrus limon (lemon), Cordyline stricta (slender palm lily), Correa alba (white correa), Correa reflexa (native fuchsia), Cymbopogon citratus (lemon grass), Daphne odora (winter daphne), Dichondra repens (kidney weed), Dietes robinsoniana (Lord Howe wedding lily), Eremophila glabra (tar bush), Eriostemon australasius (pink wax flower), Fatsia japonica (Japanese aralia), Fragaria vesca (wild strawberry), Geranium nodosum (knotted crane’s-bill), Grevillea ‘Moonlight’(grevillea), Helichrysum italicum (curry plant), Helleborus spp. (hellebores), herb mix, Hibiscus splendens (pink hibiscus), Iris japonica (fringed iris), Lamium maculatum ‘Album’(spotted dead nettle), Liriope ‘Silverstar’ (liriope), Lygodium microphyllum (climbing maidenhair fern), Lysimachia paridiformis (loosestrife), Matricaria chamomilla (chamomile), Passiflora edulis (passionfruit), Pelargonium crispum (lemon-scented geranium), Pelargonium gibbosum (gouty pelargonium), Pelargonium graveolens (rose-scented geranium), Pelargonium odoratissimum (apple geranium), Plectranthus argentatus (silver spurflower), Plectranthus fruticosus (forest spurflower),roses selected by client, Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary), Salvia officinalis (sage), Thryptomene saxicola ‘Payne’s Hybrid’ (thryptomene), Thymus vulgaris (thyme), Viola hederacea (native violet), Westringia fruticosa ‘Mundi,’ Westringia fruticosa ‘Smokey,’ Westringia fruticosa (coastal rosemary)

Plant list (indicative) – Rear garden

Actinotus helianthi (flannel flower), Alyssum spinosum (spiny madwort), Banksia robur (swamp banksia), Bracteantha bracteata (golden everlasting), Brunonia australis (blue pincushion), Chrysocephalum apiculatum (yellow buttons), Conostylis candicans (grey cottonheads), Correa glabra (rock correa), Crassula multicava (fairy crassula), Dichelachne crinita (longhair plume grass), Dichondra ‘Silver Falls’(dichondra argenta), Dichondra repens (kidney weed), Disphyma crassifolium (rounded noon flower), Lobelia alata (lobelia), Lomandra ‘Little Con’(mat rush), Poa labillardieri (common tussock-grass), Scaevola calendulacea (dune fan-flower), Scleranthus biflorus (two-flowered knawel), Soleirolia soleirolii (baby’s tears), Westringia fruticosa (coastal rosemary)

Credits

- Project

- Clifftop garden

- Design practice

- Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture

Sydney, NSW, Australia

- Project Team

- Jane Irwin, Dan Harman

- Consultants

-

Architect

Paul Pholeros

Contractor Bates Landscape Services

Natural pool and pond Puddleton Gardens

- Site Details

-

Location

Vaucluse,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 2 months

Construction 1 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Outdoor / gardens

Source

Review

Published online: 17 Jan 2020

Words:

David Whitworth

Images:

Dianna Snape,

Jane Irwin Landscape Architecture

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2019