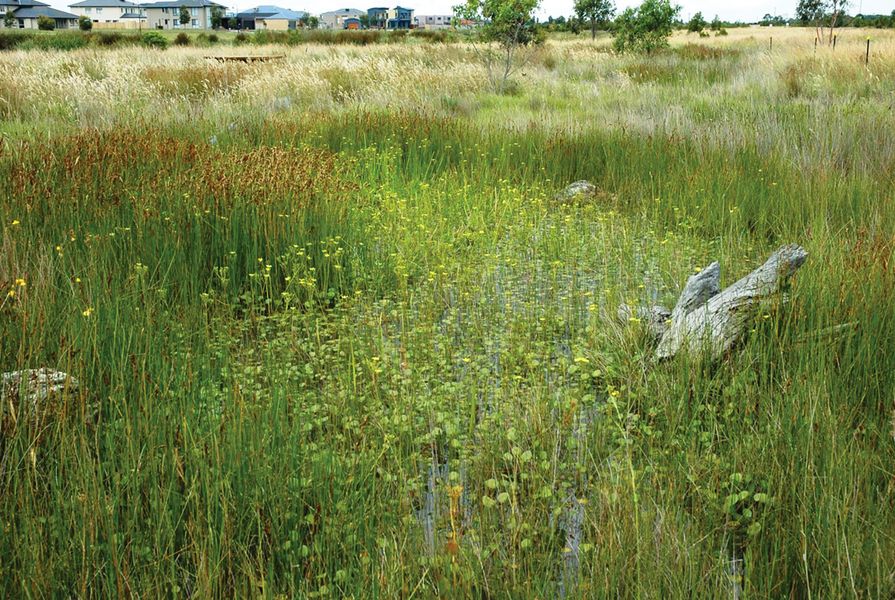

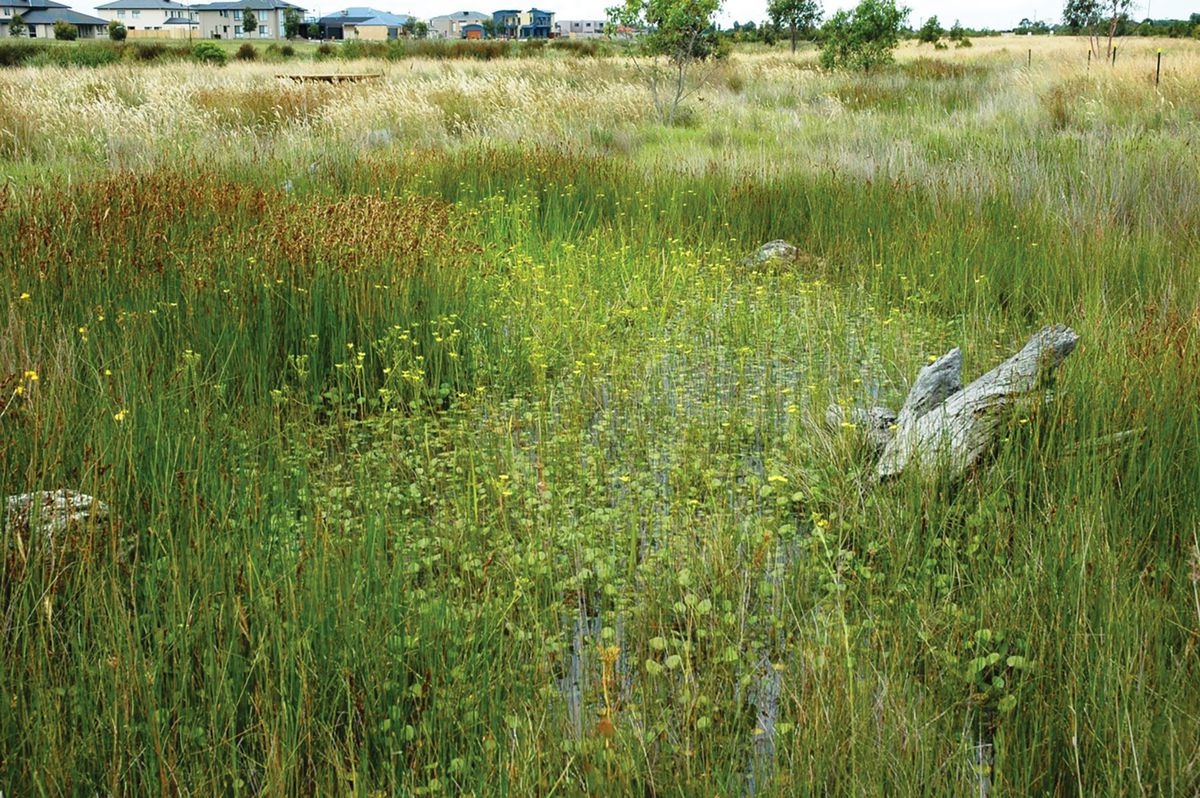

A dense sea of pitched roofs, domestic gardens and clipped lawns abruptly gives way to an abundant wetland. A pair of magpie geese perch on a log, insects hum, pelicans cruise overhead.

At Waterways, a 48-hectare restoration project located along Mordialloc Creek in Melbourne’s south-eastern suburbs, a suburban housing estate coexists alongside an expanse of lakes, bushland and riparian habitat for indigenous fauna and flora.

If we’re to successfully integrate biodiversity into the fabric of our contemporary lives, there needs to be a dramatic shift in the standard typologies of urban and rural landscapes and management systems. Waterways offers an exemplary future model that demonstrates the possibilities of adequately funded and well-managed projects.

With climate change and loss of biodiversity understood as the most pressing challenges of the decade, culturally embedded systems of management need to be established across regional agricultural systems and urban landscapes – from parks to verges to housing estates – as the new status quo.

In this interview, ecologist Damien Cook, who received the Society for Ecological Restoration Australasia (SERA) Award for Restoration Excellence for his contribution to the Waterways project, discusses the current challenges and opportunities within environmental restoration practice.

Species that have been established in restored native grasslands at Waterways in south-eastern Melbourne include grey billy buttons (Craspedia canens), matted flax-lily (Dianella amoena) and pale swamp everlasting (Coronidium gunnianum).

Image: Damien Cook

Sarah Hicks: What are some of the key projects you’ve been working on recently and what has been your role?

Damien Cook: Recently, I’ve been working with the Barapa Barapa and Wemba-Wemba people, who are the Traditional Owners of the area between Cohuna and Swan Hill in the Murray River Valley within the Water for Country Project Group (in partnership with the North Central Catchment Management Authority) on grassland restoration. The communities were seeking to replant grassland bush tucker, including yam daisies [murnong or Mirrwan in the local language], bulbine lilies and other edible tuberous plants and to improve the condition of wetlands that had been degraded because of poor water- and land-management practices.

Prior to modification caused by European land use, the wetlands had a natural wetting and drying cycle, flooding every couple of years and drying out after hot, dry weather – wetting and drying is really critical to the functioning of these kinds of ecosystems. From the 1970s through to the 1990s, the wetlands were used for water storage and this drowned all of the trees and degraded the understorey.

Wemba-Wemba revegetation underway at First Marsh in Koorangie Wildlife Reserve in Gannawarra in northern Victoria.

Image: Damien Cook

Since the beginning of this century, the catchment management authorities have been managing the water levels in the wetlands, simulating the wetting and drying conditions of when they were natural swamps. This has allowed us to begin to restore the canopy of indigenous trees and the ground layer.

We discovered a remnant grassland area at Johnson Swamp, about 15 kilometres south-east of Kerang, that had a really good structure of native grasses but was missing the herbaceous component, the bush tucker component. All we really needed to do was weed management and planting. We applied strategic burning and a really particular technique called “de-fertilizing” through the application of sugar, which stimulates the soil bacteria and absorbs nitrogen out of the top layer of soil. Most farmers are laying down phosphate-based fertilizers to increase the productivity of the pasture, but when restoring a grassland, you need to extract some of the nitrogen and swing the conditions back in favour of the native plants.

SH: What is your role in working with the Traditional Owners, the Barapa Barapa and Wemba-Wemba people, on these sites? What’s your process of engagement?

DC: I play an advisory role in terms of techniques in doing restoration work. I’m guided by the Traditional Owners in species selection, as there is often a focus on culturally significant plants such as common nardoo (Marsilea drummondii) and water ribbons (Cycnogeton procerum). One plant that’s been of particular interest, for example, is old man weed or Centipeda cunninghamii, which is a prominent medicine plant for the Barapa Barapa and Wemba-Wemba people.

So, my role is to coordinate and provide assistance on species selection for a site’s specific conditions. I source the plants and materials for the project and introduce techniques such as direct seeding or hand planting. Experienced members who’ve been involved in a few projects might manage sites independently. It’s a great way of generating employment for the area; however, it’s usually project-by-project work. For a serious proposition, where people might make a career out of this work, we need more consistent funding to employ people to carry out the restoration work. There’s about 30,000 acres [more than 12,000 hectares] of wetlands that could be restored, just in the North Central Catchment Management Authority area.

Aquatic planting at McDonald Swamp, a regionally significant wetland of 164 hectares in north-central Victoria.

Image: Damien Cook

Marsilea drummondii (nardoo) planting at McDonalds Swamp.

Image: Damien Cook

SH: When working with a new site, what’s your approach to making an assessment and planning management?

DC: You basically look at the site, its soils and landforms and the species on it, which is a way of understanding and reading the landscape and getting a sense of its past management and history of disturbance. Often, the plants tell you the story. But part of the process is observing, rather than just jumping straight in and trying to do something. It’s best, if there’s the opportunity, to look at a site over a year to observe it in different seasons. You might look at a site in summer and not see many weeds, but return in winter to a site full of weeds that had been dormant over the warmer months.

It also depends on what the objectives are for the site. If it’s a really big site, for instance, you might prioritize the issue of the woody weeds, rather than the annual grasses, because it’s going to have the most impact straight up. But then you’ve also got to consider that the woody weeds might be providing habitat, and how to do a safe removal when you replace an area [of them] to ensure that habitat is maintained throughout the process.

The Society for Ecological Restoration resource database has some really useful tools, including one called the Primer on Ecological Restoration. It provides step-by-step approaches to what to consider [when undertaking a restoration project] – I highly recommend it for anyone who’s thinking of doing this sort of work.

And then it’s about actually looking at a reference ecosystem (EVC) that might provide a living example of what you’re aiming for, seeing if you can find something in the landscape that is the ultimate goal, in terms of species, plant density and reference conditions.

Downy swainson-pea (Swainsona swainsonioides) at Johnson Swamp, a 340-hectare wetland near Kerang in the north of Victoria.

Image: Damien Cook

Murnong growing at Johnson Swamp.

Image: Damien Cook

SH: The UN has just launched the Decade on Ecosystem Restoration. What do you think needs to happen locally and across Australia, more broadly, to make real progress on this task?

DC: It’s a huge task, there’s no doubt about that. Over the last couple of hundred years, we’ve been an incredibly potent force in the destruction and degradation of the natural environment. Colonization has been the seat of massive destruction of [indigenous cultures] and biodiversity across the planet. Despite this, many of these cultures (living in places such as Australia) have managed to survive, alongside incredible biodiversity.

A good example of a recent large-scale project is the Loess Plateau. The site is a vast area in the semi-arid part of China that had been over-cleared, was facing huge erosion issues and [had been rendered] agriculturally unproductive. The Chinese government initiated a massive reforestation program employing a local labour force. The project is one of the world’s largest erosion-control programs and a good example of what can be done on a large scale, with decent resourcing and with the expertise of local inhabitants.

So, we just need that, times a million. I think that in Australia at the moment we don’t have political leadership to move forward – we can’t even stop species decline. We’re one of the worst countries in the world for both mammal extinctions and vegetation clearing. So, we’ve really got to put the brakes on that and think about how we’re going to restore the environment.

There are certainly positive sides, including regenerative farming – a lot of farmers are now looking at farming in a different way. But it’s going to take a huge change in the way our political leadership resources these initiatives and it’s going to take a big cultural shift as well.

Source

Practice

Published online: 13 Aug 2021

Words:

Sarah Hicks

Images:

Damien Cook

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2021