The recent growth in debate around gender politics, both in Australia and globally, has forced us to rethink the impact of gender inequality on our public, private and professional lives. However, recognizing how this issue plays out on an individual scale, particularly in any one profession, can be difficult. Last year, as I was looking through readings assigned to me for a design theory course, I realized that the reading list, in all its diversity, was entirely made up of male authors. Suddenly it clicked. I began researching, writing and presenting about women in landscape architecture. I learnt that regardless of talent and experience, gender is still a defining factor that characterizes successful landscape architects. My gender means I will earn less for doing the same work; it means I am more likely to work part time; that perhaps I won’t ever be a director. My gender also means I will be discouraged from becoming a mother, that it will be tough to return to work after pregnancy. The list is endless. But it is not hopeless.

A shift is taking place, and Simone Bliss, the director of Melbourne-based Simone Bliss Landscape Architecture (SBLA) and a recent mother of two, is reimagining the way a landscape architecture practice can be run. She knows that supporting parenthood and letting women flourish in the profession will benefit the entire built environment industry and consequently, the public realm.

From a young age, Simone developed an interest for understanding the different systems of the Australian landscape, both built and natural. Growing up in the inner-west of Melbourne, Simone remembers seeing the city flourish – “the Eureka tower, the Commbank building, all from the balcony of a house that my papa built from scratch.” Her mother was an avid gardener – Simone often spent her weekends “building cubby houses, planting ferneries and new garden beds of native plants.”

Prior to founding SBLA, Simone worked as a senior landscape architect at Taylor Cullity Lethlean (TCL) for twelve years. Although she is sincere when she describes TCL as having a wonderful, close-knit office and supportive atmosphere, Simone could not see herself changing the way she worked within the firm when she fell pregnant with her first child. Could having children go together with her passion for landscape architecture? She looked for women within the industry who balanced work and raising a family to analyze how the two could work hand in hand. She found “few and far between.” All the female directors she looked to for inspiration were childless. Very few colleagues could recommend female directors, either in landscape architecture or in architecture firms, who were mothers of young children while working on mid-to-large-scale public projects.

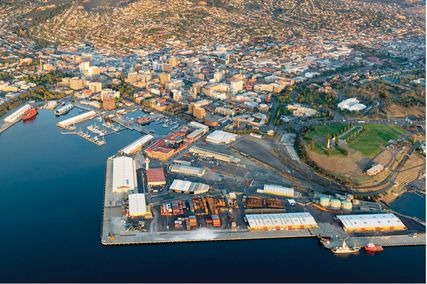

While on maternity leave for her first child, Simone realized there was “more to it than fitting in as much career as possible into a week.” Her needs had changed. Simone wanted to test if she could turn to clients and say, “I only work three days a week but I can still deliver this project.” This transition began with Playstreet, a Tasmanian landscape architecture studio. For a year, Simone worked for them from Melbourne, using Skype, GoToMeeting and Slack – digital tools that allowed for a way of connecting that did not rely on email and allowed for digital design workshops to take place.

Simone Bliss is the director of Melbourne-based Simone Bliss Landscape Architecture (SBLA) and a recent mother of two.

Simone started SBLA in 2016. Today, the office is located in Hip V. Hype, a shared space in Carlton North from which a number of other small businesses operate, all within the building and environment industry. SBLA is made up of six core members who all work part time, with backgrounds ranging from architecture, urban design, interior design, and industrial design to landscape architecture. Just like Simone, four of her employees had worked for larger companies in the past and decided to seek an alternative way of working after having children.

When I ask Simone how feminism relates to SBLA she says, “it’s at the heart of it, it’s fundamental, to make sure that everyone is equal.” She wants to prove that “it’s possible to be a director, to be a mother, and to do it well.” Simone is living proof that becoming a mother should not equate to losing your skills and your position within the profession. Going on parental leave, particularly for women, does not mean that your priorities shift or that “you don’t have as much time or passion for your career.” Instead, parenthood has made Simone more passionate about her work. She has learnt to think laterally, to be adaptable and flexible –she has become better at problem solving as a result of raising a small child. These qualities feed back into her practice, both in terms of her position as a director and as a designer.

Instead of appointing an acting director while Simone is on her second maternity leave, she is leaving it up to the team to negotiate resourcing, management of projects and design decisions. SBLA aims to have an egalitarianism approach to a typical office hierarchy. She was inspired by a friend in the corporate industry who assigned a different employee each month as director, regardless of level of experience or title.

Simone is not only interested in breaking the hierarchal dynamic of “director versus subordinates.” She also wants to break away from the typical physical environment of a studio, a lesson learnt from Playstreet. Three members of SBLA work remotely and rely on online applications to communicate with Simone. “It seems to be working so far,” she says. “Project deadlines are met, meeting dates are negotiated and our clients seem satisfied.” Furthermore, her employees are encouraged to move their working hours around and find times that suit them, their children and their own personal interests. This way of working “keeps everyone fresh,” she says.

“Most people in the creative industry don’t function in the same way – sitting by a desk all day doesn’t work for everyone. So why limit that?”.

“Where do you see SBLA in the near future?” I ask Simone, curious to hear about a potential expansion, which would naturally lead to her mode of practice gaining prominence in the profession. “I’m interested in the notion of expanding and contracting outside of our core group in the form of a network,” she says. “I don’t want skills and creativity to get lost in numbers.” Instead, Simone wants to see a shift in the way that landscape architecture practices interact with each other. Simone believes that given the broad range of skills and specialists within landscape architecture, the field could see great benefits by dismantling the current competitive way of working between firms, where secrecy and individual merit rule. She imagines a profession where skills, resources and even offices are shared; where staff members work between two or more studios; where it is “less about a name being associated with the practice and more about the group of people that deliver [the project].”

“So it’s happening,” Simone says, “but it will take time.

“With each generation, it’s going to get more and more refreshing.”

Flexibility and adaptability are at the heart of Simone’s practice and ideals. Not only in terms of motivating and supporting parenthood, but in terms of the necessary collaboration across the construction field. “This idea of flexibility needs to be open to everybody,” she says.

“It’s not just about mothers or fathers, it’s about everyone.”