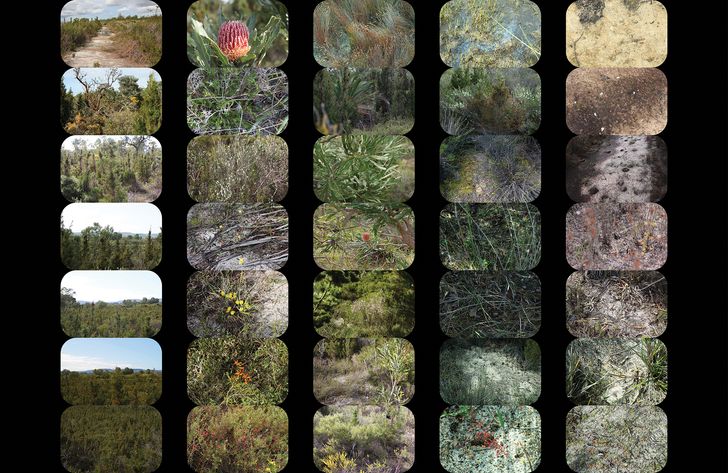

Here, we are in an ancient landscape suspended in time. We are on Whadjuk Noongar Boodjar, the Country of the Whadjuk Noongar people. Cared for over generations. We could be hovering here a thousand years ago. Hues of flora – buttery, emerald, hazel – paint a gradient between the gradual dunal rises and claypan flats. At our feet, a thick crust of land is smudged by fungi and water, soaking and drying like a sponge, a microcosm of the tapestries of streams and wetlands across the whole of this Boodjar (Country). We see scratchings of kwindas (southern brown bandicoots), native bees stuck to braided drosera beneath an old-growth shrubland. Against the sun, the ngoolark’s (Carnaby’s black cockatoo’s) screech and flicker, perching to feed on mundjit (Banksia menziesii). The Kartamoarnda (the black hills or Darling Scarp) press down upon this landscape and feed it with water, reminding us that the flows are deep and wide. We are immersed in a richly woven fabric – otherwise known as an ecosystem – vital and interdependent.

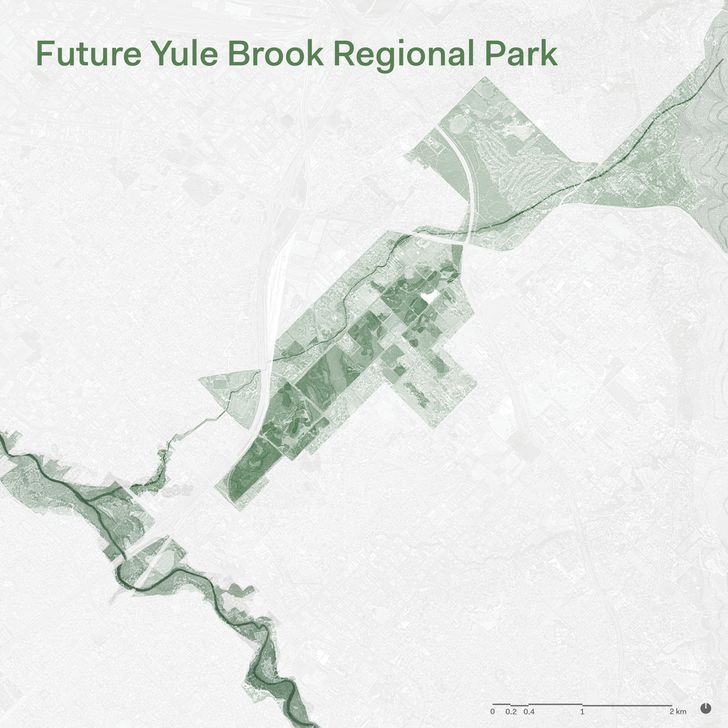

Mandoorn (Yule Brook) flows from the edge of the Kartamoarnda at Jerban (Lesmurdie Falls) to the Dyarlgarro (Canning River) where it flows into the Derbarl Yerrigan Bilya (Swan River) and to the ocean. Over 10 kilometres, Mandoorn makes up a 702-hectare corridor – an area of ongoing advocacy for a future Mandoorn or Yule Brook Regional Park. This regional conservation protection is now urgent. The South West of Western Australia is one of 36 internationally-recognized biodiversity hotspots. Often expressed as an accolade, a hotspot is in fact a condemnation. The classification is given where globally significant biodiversity is in escalating conflict with human impacts. The highest concentrations of biodiversity in WA’s South West occur within four regions: the Fitzgerald Biosphere, Koi Kyenunu-ruff (the Stirling Ranges), Lesueur National Park and the Perth region. Mandoorn contains around 70 percent of the floral species in each of these megadiverse regions, concentrated in less than one percent of the area.

Mandoorn sits entirely within the Perth metropolitan area, surrounded by small rural lots and expanding suburbs and industrial areas.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin

At Mandoorn, loams meet leached sands, igneous rocks meet riverine flows. The nearby rocks up at Kartamoarnda are part of the Yilgarn geology thought to have formed 4.4 billion years ago. This makes this landscape the oldest in the world. The top layer of sand down here at Mandoorn is relatively young, about 2 million years old, with a complex of ecosystems establishing soon thereafter. Where these old and new, flowing and static systems meet, biodiversity skyrockets. There are 857 endemic species of flora here, 58 rare and threatened flora, and 11 federally listed threatened ecological communities. In this corridor, there are 36 carnivorous plant species, far more than in the whole of Europe, and an estimated 80 species of native bee. There are two species of threatened black cockatoo (the forest red-tailed and the endangered Carnaby’s white-tailed), and the near-threatened chuditch (western quoll). Yet, the formal protection of this corridor is only 400-metres-wide, and the urban system is mounting a conflict across its edges.

Here, at Mandoorn, we are entirely within the city – and these “remnants,” in this context, have a special significance. More than “remnants,” they are the ancient landscapes of this place and raise many questions. How should a city shape itself to conserve or connect to ancient landscapes, such as these? How should we design with them? Kenwick Station is less than 100 metres from the southern edge of Mandoorn, a short 17-minute train ride to the Perth CBD, and the area surrounding the station is flagged for commercial activation and housing densification in the near future. Perth Airport is 10 minutes by car (or truck) and hundreds of hectares of private rural land surrounding the corridor have been flagged for industrial development since the 1990s. With the inertia of planning behind it, development is now imminent with a major new industrial estate, the Maddington Kenwick Strategic Employment Area (MKSEA). Another question: what processes in play must we pause, so that planning can recalibrate around culture, climate and conservation?

Hues of herblands and sedgelands form subtle, biodiverse ecotones.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin

High-fidelity ecotones glimpsed in the sandy ground – and some of the area’s 857 floral taxa.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin and Alice Ford

Much of the business-as-usual development in Perth has shown us that a hard and violent edge is set to develop between Mandoorn and the urban area as the above plans progress. The small rural lots adjacent to Mandoorn would be cleared, drained and benched with sandy fill to many metres above the natural ground level. Encircling development will foreseeably constrict the corridor to the width of the “remnant,” leading to an increase in urban heat and a decrease in ground permeability. Mandoorn sits on intricate layers of clay and sand, forming a fragile hydroplain that connects to the deep aquifer system beneath the city. Many of the ecological communities here are dependent on these layers of water flowing laterally on clays from the permeable rural areas nearby. There is substantial concern among local scientists about these impacts, as the hallmark conflicts of our biodiversity hotspot are on full display.

Places like Mandoorn raise the significance of remnant landscapes as part of a gradient of “natures” or ecological paradigms within the city. We know that equating nature to wilderness and framing it as something “out there” beyond the city has long distracted us from comprehending hybrid ecologies within cities. However, in this context, urban ecologies mean more than the birds and the bees on our balconies or the urban forests in our verges and backyards – Mandoorn shows that cities can also include ancient high-fidelity ecosystems.

Rather than a hard edge between development and Mandoorn, the ecological and hydrological knowledge suggests that this edge needs to be much wider and softer, incorporating broad buffer zones. And far from a buffer zone that excludes people, imagine an active buffer that connects people, culture and place within an expanded Yule Brook Regional Park. This approach begins to form a landscape gradient – one that can extend beyond the buffer into sensitively-designed housing regeneration and industrial development to support a softer edge. There is an opportunity here for landscape architects, planners and urban designers to advance design, together with conservation, to explore a reciprocal edge between urbanism and ancient landscape.

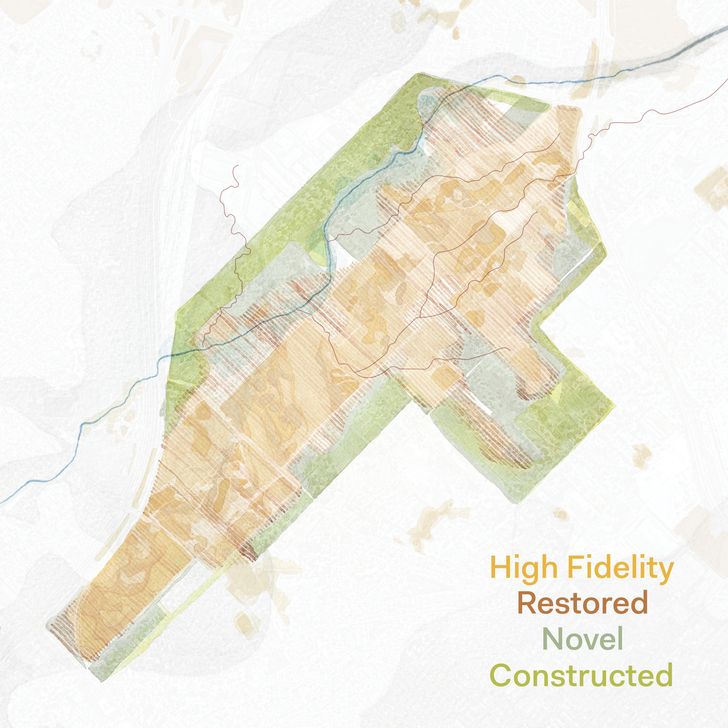

A gradient of ecosystem types informs the strategy for Mandoorn’s broad buffer areas.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin and Alice Ford

The ecosystem paradigms developed by ecologists Richard Hobbs, Lauren Hallett, Eric Higgs and others are a helpful reference. They refer to many “natures”: a gradient from high-fidelity ecosystems, through restored, hybrid, novel and constructed ecosystems. These types currently form a gradient across Mandoorn. At the centre is a core of high-fidelity landscapes, at the edges of this core exist modified and hybrid ecosystems, including novel ecosystems. Typical for novel ecosystems, these edges have been designated as “completely degraded” and hence, developable. Here, as in many places, these degraded areas are critical to environmental function, they are home to many species, they provide a buffer and catchment for the high-fidelity areas.

Conserving this gradient of “natures” at Mandoorn raises rich landscape potentials. Within an expanded buffer zone, there are opportunities for restoration, opportunities for designed and constructed ecosystems – for parks, play areas, nurseries, farmers markets – uses which support Mandoorn and knit into the urban environment and blue-green matrix of the city. In a multivalent buffer zone such as this, some areas close to the core should effectively be left alone, while other areas at the edges can be made and designed. Of course, this strategy itself is a design, and there is a role for landscape architects in advocating for these places in an urban context to bring together design and conservation.

The landscape of Mandoorn connects Jerban to Dyarlgarro through a megadiverse 10-kilometre corridor.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin and Alice Ford

Such a strategy challenges conventional planning, environmental and regulatory toolkits spatially and temporally. Spatially, because those frameworks are often blind to thinking between boundaries and across landscape systems. Temporally, because they rarely account for the cumulative impacts of multiple developments over time or leave much possibility for future emergence. Taking planning deeper and wider to comprehend and care for urban ecological systems is imperative as our climate and biodiversity emergency escalates. Within this potential 702-hectare Yule Brook Regional Park, an expanded buffer will not emerge at once or even quickly. This is a vision that extends over many decades – with potentially dozens of projects, with dozens of designers. It requires that we leave areas for future potential, for the emergence of the human and more-than-human, across ecosystem gradients. Such an approach requires moving slowly, leaving agency for community and culture to interpret and act, and of course for future generations.

1. Hans Lambers (ed.), A Jewel in the Crown of a Global Biodiversity Hotspot, Kwongan Foundation, Perth, 2019.

2. The Beeliar Group of Professors for Environmental Responsibility, “A vision for conservation and public enjoyment of the Greater Brixton Street Wetlands and an eventual Yule Brook Regional Park,” The Beeliar Group website, 2018, https://thebeeliargroup.com/our-statements/ (accessed 2 June 2022)

3. See various chapters in Richard Hobbs, Eric Higgs and Carol Hall (eds.), Novel ecosystems : intervening in the new ecological world order, John Wiley and Sons, West Sussex, 2013

4. The author thanks Sandra Harben for the many yarns about place and time as part of this work and research on Whadjuk Noongar Boodjar. The author also thanks The Beeliar Group, in particular Hans Lambers and Andrea Gaynor, for their contributions to this project.

Source

Practice

Published online: 16 Sep 2022

Words:

Daniel Jan Martin

Images:

Daniel Jan Martin,

Daniel Jan Martin and Alice Ford

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022