To the casual visitor, a trip to the South Bank precinct is a visit to the heart of Brisbane and the best that life in Queensland offers. The lush, shady gardens and groves, the sunny lawns that overlook the CBD and the Brisbane River, the vivid bougainvillea-clad Grand Arbour that snakes along its length, the sounds of birds – all are memorable. Within walking distance of the CBD, one can dine or snack al fresco, swim in turquoise lagoons, meet friends and colleagues and connect with the city’s cultural life. The Convention Centre and cinemas, the Cultural Precinct with its theatres, concert halls, museum and galleries, and Griffith University’s art school and conservatorium of music are all either on site or within walking distance. So too are hospitals, hotels, offices, schools, a TAFE and the growing neighbourhoods of West End and South Brisbane. With so much on offer, South Bank is often touted as an ideal place to live or work.

As one of three inner-Brisbane precincts first conceived in the 1980s, South Bank has evolved since World Expo was staged on its site in 1988. It provides lessons not only about how urban landscapes of this scale are initiated but also about the risks that confront them over their lifetimes. The Cultural Precinct next door is home to the state’s major cultural institutions, museum, theatres and galleries. Across the river, in the Gardens Point Precinct, you’ll find QUT, Parliament and the City Botanic Gardens. At their inception, all three precincts shared strong, well-argued plans that explained why they should be considered and managed as precincts, rather than as groups of sites for individual development. Those plans drove an immediate response by their principal landowners – the Queensland government, the Brisbane City Council and QUT – and resulted in the reconfiguration of land and funding for their initial construction. Beyond this, however, their paths diverged. The South Bank Corporation Act 1989 established South Bank Corporation as a government-owned statutory authority with an independent board. This structure – unique at the time – meant that South Bank alone had a commercial dimension to fund precinct upkeep and contribute capital to site redevelopment. Considered a success, this governance model has now become the preferred form of precinct development, governance and management throughout the state.

An aerial photograph of Brisbane in 1986, taken just prior to the beginning of construction on Expo 88 at South Bank.

Image: Queensland State Archives

Designers tend to think in terms of typical project time frames of perhaps three to six years. But broader precincts are delivered and managed over much longer periods, and to be effective, designers need to understand the way change operates in these environments – not only in planning, strategy and construction, but in governance and management. If, as design professionals, we are well-versed in ecology and sustainability, then we will already understand change over the course of natural life cycles and consider this in our practice. But are we equipped to contribute what landscapes need in such diverse and intensively managed settings across whole lifetimes? When the inevitable removal or reconfiguration of use is required in response to changing circumstances, do we understand how to respond by making lasting contributions to site quality?

Over the decades, I have been involved in the planning, design and management of many urban precincts. These include Brisbane’s South Bank, Cultural Precinct and Gardens Point, where I have been planner and strategist, urban and landscape designer, commentator and advocate, design reviewer and, most recently, chair of the board of South Bank Corporation, which oversees the precinct’s 42 hectares of commercial, residential, institutional and landscape development. I am also a member of the local community. To be effective in any of these roles, one needs to understand what processes are at play at that time, what or who ultimately decides what happens, and how it happens (in terms of governance and management). Then one can choose, whatever the circumstances, how best to contribute and perhaps even guide the process of change itself.

South Bank under construction, circa 1990.

Image: courtesy South Bank Corporation

Expo 88, overseen by architecture firm Bligh Maccormick 88, was a springboard for the development of South Bank.

Image: Queensland State Archives

Despite the best intentions of planners and designers, in urban environments very little stays the same. Changes occur not only to the fabric of the place, for as culture evolves, users and their expectations also change, as do the systems of governance, management and funding. Designers need to respond to and anticipate this reality, manipulating space and form to prioritize those elements that provide places with a continuity of structure, rather than the more ephemeral detail. Designers also need to use their professional expertise to inform the systems that manage how such places evolve. This might mean ensuring that the key factors that affect the survival of designed landscapes are monitored – including intensity of use, the consumption of resources such as water, waste and workload, and the evolution of a reconstructed ecosystem – and that there is the expertise to respond to change and adapt as required. If we have ensured that the feedback loops are in place, and that threats and problems are addressed by management as they appear, then we are, as professionals, recognizing and working with time in the urban landscape and the change that time inevitably brings. If we also use our expertise to inform the systems of governance that underpin place management, we contribute even more.

With its diverse offering, central location and broad remit, South Bank has, over the decades, experienced change at its best and worst. The prime location and a never-ending thirst to increase popularity and funds have generated demand, not only from its state owners and commercial operators and lessees, but from users and stakeholders. Activity and financial yield are always expected to increase and the site has to adapt. In 2019, there were 14 million visitors to South Bank, with more than 8 million of these to South Bank Parklands, including, as testament to their enduring appeal, 4 million each to the Grand Arbour and the Clem Jones Promenade.

Under contemporary governance and management models, those ultimately responsible for setting direction and making decisions tend to bring knowledge of fiscal and commercial issues to the task, rather than knowledge of how successful urban sites are best created and sustained. It is a constant challenge, therefore, to ensure that they are kept informed and consider issues of quality when decisions are made. Among South Bank’s many positive aspects, visitors with expertise will recognize the results of aging infrastructure and inconsistent decision-making over its three-plus decades. Fault lines are beginning to show, with some buildings poorly sited or scaled, open spaces worn or lacking in usefulness and few references to the site’s rich Indigenous history among many to other cultures. Pedestrian connections beyond the site lack simplicity and, in some instances, dignity.

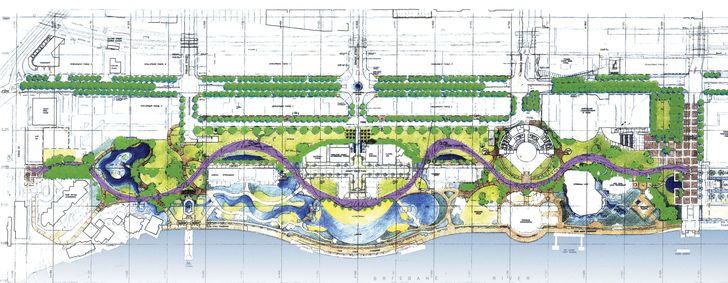

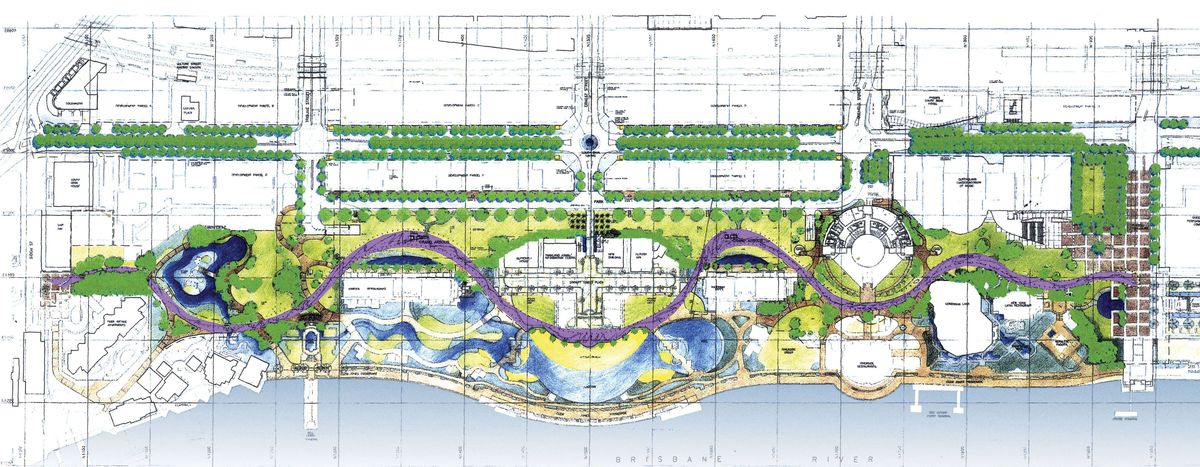

The issues that were most relevant at one life stage are superseded at another, and owners and, ideally, managers must have the capacity and the resources to respond in the moment – always a challenge with competing demands on the public purse. Following Expo 88, an initial design for commercial development of the South Bank site was prepared by the Expo designers, landscape architecture practice Media 5 and architecture practice Desmond Brooks International. But when the government of the day responded to community expectations and kept the site in public hands, a new site management team commissioned Denton Corker Marshall from Melbourne to prepare masterplans in 1997 and 2007. Currently, a third masterplan is underway, led by Urbis. To have kept up with and best directed change, I would argue that there should have been at least two more masterplans commissioned within this period, with parallel updates of the systems that regulate on-site development and guide funding, consistent with the site’s fundamental purpose. That purpose is described in South Bank’s initial legislation and, in summary, is to provide a balance between social benefit and commercial outcome and a diverse offering that complements rather than duplicates others. While the charter has been invaluable in guiding the site’s evolution and in assessing options for change, site character is always at risk from pressure to develop and decisions are best assisted by up-to-date masterplans and regulatory systems that directly relate these broad intentions to the specifics of spatial structure.

Denton Corker Marshall’s 1997 masterplan for South Bank features some 15 hectares of parklands and a grand arbour, and is divided into a river spine, a park spine and a street spine.

Image: Denton Corker Marshall

As at other urban precincts, demand at South Bank is considered a primary measure of its success, and that demand must be continually managed to prevent the erosion of site character through the inadvertent loss of core qualities from overuse and inappropriate development. The precinct’s core attractions include remnants of the earliest designs, including the swimming lagoons, beaches, gardens and the Clem Jones Promenade. They also include later additions, such as the iconic Grand Arbour by Denton Corker Marshall, and River Quay, a dining area by Arkhefield and SPLAT that overlooks the city and gives rare access to the river. Most recently, these have been joined by the first stage of a new open space designed by Hassell. Riverside Green replaces a group of outdated restaurants on a prime river’s edge site at the precinct’s heart. Recognized by multiple design awards and intensively used, not only are these three projects the work of excellent design teams, they are the result of South Bank Corporation’s robust internal processes, including expert design procurement and independent design review, both of which directly informed decision-making by South Bank’s management and board. They are, however, just a few of the nearly 20 projects of all types, scales and as many design teams that I estimate have reworked almost every corner of the precinct over the period of my involvement. Challenges to site quality continue. What has been successful, why and for how long are questions that generate vigorous and ongoing debate. While such debate is assisted by the monitoring that management regularly commissions to understand the dynamics, dimensions and qualities of site appeal, it is best enhanced by the critical capacities of well-briefed design experts.

An aerial of South Bank taken in 1992. Today, the precinct’s core attractions still include remnants of the earliest designs, including swimming lagoons and beaches.

Image: courtesy South Bank Corporation

Riverside Green by Hassell replaced a collection of outdated restaurants on the edge of the Brisbane River with a public space that includes a “rainforest deck,” pavilion and events lawn.

Image: Scott Burrows

Spatial planning and design are unique skills that remain a mystery to many. While the practice of urban design usually works in parallel with the systems of urban management and governance that provide its context, the landscape architect’s knowledge of natural and created worlds and the urban designer’s knowledge of urban systems can improve those systems from within, increasing the likelihood of change being successful in urban areas over time. However, to work effectively at the urban scale, guiding as well as responding to the complex processes at play, both roles need to expand their range of skills and bring these into new working domains. Decision-making, governance, site management, project procurement, monitoring and funding would all benefit.

South Bank is built on the land of the Turrbal and Yuggera people.

Source

Practice

Published online: 17 Aug 2022

Words:

Catherin Bull

Images:

Denton Corker Marshall,

Queensland State Archives,

Scott Burrows,

South Bank Corporation/Aerial Advantage,

courtesy South Bank Corporation

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022