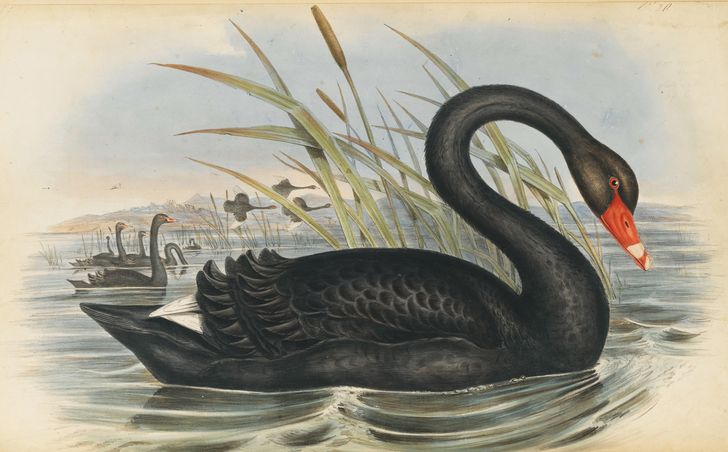

Over its 40-year life, the Maali (black swan) bonds with one other partner. Younger Maali will breed several times a year, losing their white flight feathers each time, and gathering as a flightless flock to raise their young. Maali exchange roles. Some become the carers of the large, lustrous, pale green eggs, adopting any that have been abandoned. After regaining flight, other Maali will leave the nests to explore new horizons throughout Perth’s tapestry of rivers, streams and wetlands – fresh, brackish and saline. Cygnet hatchlings are fiercely defended by the Maali as they are taught to drink from the sheet of freshwater that glazes the saline Derbarl Yerrigan Bilya (Swan River) after rain. They learn to feed on soft grasses along the river edge and dive for aquatic plants. An understanding of the intricacies of the Maali fosters an ability to care and begin the reparative work for these creatures whose habitats and future are at risk.

Djirda Miya is a recent project created in Buneenboro (Perth Water) that may signal a change in human engagement with Bilya: one that foregrounds “more-than-human” inhabitants and processes. At a glance, the island emerges as a jarring object interrupting a continuous river edge. But on closer inspection, it teems with birdlife, even though construction was completed only months ago, in September 2021. Djirda Miya means “home of the birds” in the language of the Whadjuk Noongar, the Traditional Owners of the south-west of Western Australia, speaking to the reality of the Bilya for at least 60,000 years of Noongar inhabitation. This was once a place filled with birdlife. The Maali remain a charismatic keystone species throughout the south-west ecoregion, demanding Instagram attention, political action and project funding. Charismatic species are important as stepping stones toward broader restoration efforts.

The Maali is a charismatic keystone species in the south-west ecoregion. Illustration from The Birds of Australia by John Gould.

Image: John Gould

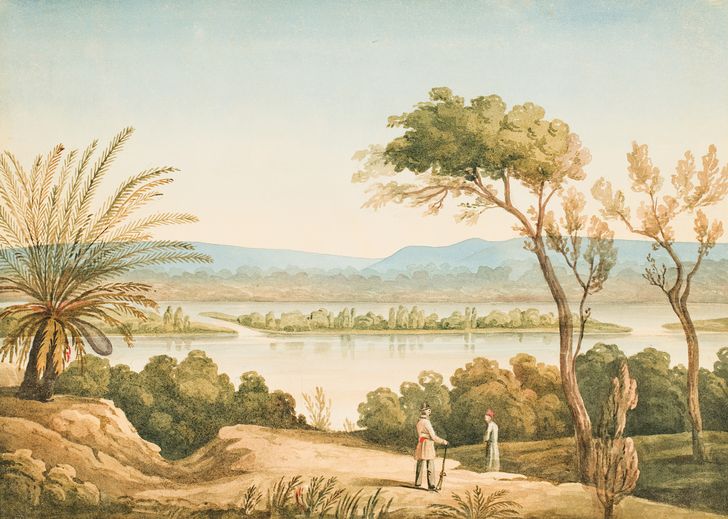

In 1829, Derbarl Yerrigan Bilya was proclaimed the “Swan River” and the whole region the “Swan River Colony” by British invaders. Typical of the colonial treatment of Australian urban river systems, the ecology of the river was drastically modified, and the swans began to leave. Hard river edges and steep walls were constructed to control the watercourse’s seasonal ebbs, flows and inundations. These walls became barriers, forcing a distinction between the domains of the natural and the cultural. Seasonal sandbars were dredged and limestone cliffs were exploded to construct the Fremantle Port. While the water was once mostly brackish, it has now become predominantly saline through its lower reaches for most of the year. Today, this modified natural system needs to be managed for resilience in the face of growing pressures from climate change, urban development, industry and human recreation.

A bobcat shapes the sand and rock of Djirda Miya island during the construction process in 2020. Photo: City of South Perth.

Image: City of South Perth

An early view of the Swan River in Swan River – View from Fraser’s Point by Frederick Garling (1827).

Image: Frederick Garling

In this context, Djirda Miya is a critical step toward restoring habitat throughout the river. It is the culmination of decades of work, beginning with Bringing Back the Swans , a 2000 report advocating for the establishment of Maali havens throughout the river.1 Djirda Miya is the most substantial of these to eventuate so far: a deposition of sand armoured by biscuit limestone that provides a safe breeding ground and launching pad for native waterbirds, while sheltering and replacing an eroding riverbank. The South Perth Foreshore Strategy and Management Plan (2015) outlined the local planning for the island, integrated nodes of activity and ecology to form a cohesive vision for the riverfront. Guided by Bamford Consulting Ecologists, the City of South Perth’s brief called for the replacement of the steep river walls with sandy beaches for birdlife. The marine engineering firm M. P. Rogers and Associates modelled this approach, demonstrating that the sandy beaches would wash away when exposed to winter storms. Worse still, over time, the river would reclaim the landfilled foreshore, exposing contaminants beneath.

The final approach takes design cues from a lagoon. A long breakwater and two headlands shield the beaches from wave action, enabling two beaches that complement each other, connecting and creating habitat. The shore beach connects the Maali with the river, while the island beach provides a safe nesting habitat away from dogs and people. The City of South Perth’s landscape architecture team worked closely with the engineers and ecologists to craft this landscape. “Free from the constraints of designing only for people, we aimed to provide resources for bird consumption,” said the council’s lead landscape architect, Tom Cunningham. “The planting palette provides birds with nesting material, food throughout the year and shelter from winds – a shopping aisle formed of endemic marine couch grass. Freshwater is provided via an overflow pipe that takes excess water from the nearby lakes and releases it into the river. Since construction, local birdlife now drink and bathe under the near-constant flow of freshwater.”

Life on the island will likely become more abundant as the planting becomes more established and the birds form their own nests. Photo: Liam Mouritz.

Image: Liam Mouritz

At the time of writing, the island shimmers with life during Kambarang, the second spring of the six Noongar seasons. These “encounters with shimmer,” in the words of Deborah Bird Rose, remind us that “the world is not composed of gears and cogs but of multifaceted, multispecies relations and pulses.”2 Following 2021’s exceptionally wet Perth winter, two cygnets have already been born on the island, demonstrating its promise as a home for birds and showcasing an alluring network of ecological activity. This landscape in motion offers a particular kind of eco-aesthetics that appeals to the senses. We observe the ephemeral pulsing and dulling according to the ecological rhythm so often beyond our reach as both humans and designers.

Thinking to the future, we are excited to see how Djirda Miya will emerge and be managed. Situated within the thriving ecotone between the river and the land, life on the island will likely become more abundant as the planting settles into varying inundation levels, shellfish occupy the limestone shelves, and the birds form their own nests using salvaged plant materials. The local community are passionate participants in the project, flocking to the nearby shore to take photos of the emerging birdlife, with the Friends of the South Perth Wetlands working in cooperation with the city to monitor bird numbers, species, breeding and migration.

Moving beyond the scale of the island, the coordinated rewilding of Perth’s riverfront should be firmly on the agenda for state and local government agencies. Although an early vison paper for Buneenboro sets the scene, a comprehensive landscape strategy needs to follow, underpinned by a vision and political will to act. In the 1960s, landscape architect John Oldham put forward a proposal for an extended botanic garden that would wrap around Buneenboro, connecting the University of Western Australia, Kings Park, the CBD and Perth Zoo. It was a grand vision and one that would embrace the Maali and a range of ecological activity throughout the river. The challenge seems to be less to do with the vision than with achieving cooperation among the many stakeholders and agencies involved to implement something that can be accepted by the community, financed and maintained. Given its success in getting off the drawing board into the water, Djirda Miya offers a valuable case study for what is possible, demonstrating the benefits of a more tactical and incremental approach to masterplan implementation.

Design has long been centred upon the needs of humans, be these functional, formal or financial. Indeed, even projects such as Djirda Miya could be framed through an ecosystem services discourse that prioritizes human interests. However, in the context of a climate in crisis and a biodiversity emergency, how human-facilitated design frames and seriously addresses the animals, plants and broader ecological processes of which we are all a part becomes ever more critical. In this challenge, there are various roles to play: to care, respect and co-create, but also to cede control to “more-than-human” forces. Deborah Bird Rose again helps us to think through this question of agency in cooperation with the more-than-human, reminding us to be grateful “for the fact that in the midst of terrible destruction, life finds ways to flourish, and that the shimmer of life does indeed include us.”

1. ATA Environmental, Bamford Consulting Ecologists, M. P. Rogers and Associates, Bringing Back the Swans: The potential to encourage more black swans onto the Swan River (East Perth: Water and Rivers Commission, 2000).

2. Deborah Bird Rose, “Shimmer: When all you love is being trashed,” in Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al (eds), Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Source

Practice

Published online: 13 Apr 2022

Words:

Daniel Jan Martin,

Liam Mouritz

Images:

City of South Perth,

Frederick Garling,

John Gould,

Liam Mouritz,

Veronica Mcphail

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2022