The lineage of landscape and the lineage of authorship overlap at a curious point, which is around the notion of property: land was first transformed into property in 17th century England and “landscape” emerged to mirror this legal transformation of ownership and space1; ideas and knowledge, including creative works, were transformed into intellectual property in the 18th century through adaptation of these same laws2. These transformations paralleled and supported the emergence of capitalism in modern Europe, sparking a destructive reordering of the world that extended globally via colonization. The earliest “landscape gardeners” worked within these emerging relationships between space, ideas, and economy, establishing an understanding of practice as client-focused service, landscape as “site” (property), and design as professionally authored work (intellectual property). For contemporary landscape architects, practice continues to focus value within property boundaries3, organize itself around client-generated projects4, privilege “expert” knowledge5, and focus on the delivery of “finished works” rather than ongoing, community-driven processes6. Acknowledging our colonial context and our profession’s lineage but feeling bound by these fundamentals poses a complex ethical challenge for Australian landscape practice.

For over a decade, Gunaikurnai Traditional Owners and Parks Victoria have developed shared practices underpinned by joint management arrangements. These practices are significant in that they challenge property-based understandings of both land and authorship – recognition of land rights recasts site as Country and opens it to shared governance, shifting the work’s values and outcomes. These include: Traditional Owners’ increasing land management capacity and reconnection with knowledge of Country; Parks Victoria’s growing capacity to “reframe” its understanding of the land it jointly manages and its role; the development of evolving management and design approaches that reflect cultural values and foreground Gunaikurnai knowledge; an expanding shift in the public’s understanding of land as Country; and the strategy’s intensifying impact beyond the scope of the management plan itself.

In Victoria, joint management arrangements are established between Traditional Owner groups with recognized native title and the state government under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic), which “recognises the ongoing connection of Traditional Owners to their traditional Country, and empowers them, in partnership with the Victorian Government, to actively participate in the management of land and natural resources within their traditional Country.” A Recognition and Settlement Agreement (RSA) steps this legal recognition towards joint management, with the Conservation, Forests and Lands Act 1987 (Vic) providing the basis for a Traditional Owner Land Management Board, which guides strategic direction within the lands overseen through the partnership.

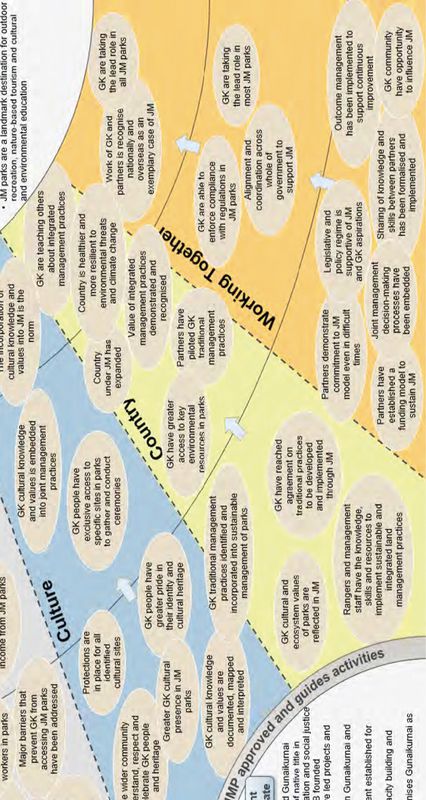

Gunaikurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation (GLaWAC) and Parks Victoria have managed 10 national parks and reserves across 47,000 hectares of Gunaikurnai Country since 2010. In its twenty-five-year timeframe, the joint management agreement aims to: reinforce the Gunaikurnai community’s connection to Country and culture; contribute to reconciliation, social and self-determination for the Gunaikurnai people; foster the wider community’s respect for Gunaikurnai heritage, connection to Country and right to self-determination; and establish healthier, more resilient parks through the integration of Gunaikurnai knowledge into land management approaches 7 . These aspirations translate into land management practices and design projects within the 10 parks and reserves, which are charted out annually by GLaWAC and Parks Victoria toward the achievement of longer term outcomes involving interconnected forms of change for people (skills, training, employment, wellbeing, education), culture (heritage, values, cultural practices), Country (sustainable environmental outcomes) and working together (governance structure and partnership).

Since Parks Victoria’s first joint management agreement with GLaWAC, three additional Traditional Owner groups within the state have developed joint management plans, while another three groups have partnered with Parks Victoria through cooperative management agreements.

The longevity of Gunaikurnai joint management allows the co-authors to reflect upon the evolution of projects and practices under the model and the outcomes realized through a partnered approach. The following are excerpts from an interview with Rob Farnham (Manager of the Gunaikurnai Rangers, GLaWAC), Matt Holland (Regional Program Coordinator Gunaikurnai, Parks Victoria) and Nick Loschiavo (Senior Precinct Planner, Parks Victoria).

The LTCAS aims to increase opportunities for Gunaikurnai people to connect with Country, foster employment and economic development opportunities and build their capacity and skills to take a central role in joint management with the other management partners.

Image: Anne-Marie Pisani

On two-way capacity building:

Rob Farnham – At GLaWAC, the joint management plan has given community members the opportunity to get through the door, especially with work. We’ve been going for 12 years now and when I first started, there were probably 11 of us staff members. Now, there’s over 50 more staff members – that’s a great thing for our community … Over time, we’ve started learning more and more, and sharing knowledge and gaining knowledge. We have a lot of mentors: Parks Victoria does a lot with our team around the project side, and we do archaeological work and cultural mapping with Monash University, and threatened species management with DELWP [Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning]. I think we will probably see GLaWAC staff members who have the opportunity to step up into roles in Parks Victoria as well.

Matt Holland – From a Parks Victoria perspective, it’s about building an understanding and a capacity within our staff to reframe how we look at landscapes and how we approach things. It’s about knowing that it’s not just ours to look after – that we need to bring GLaWAC into the conversation because we’re doing this together now. It’s not up to Parks Victoria to come up with a plan; we’re doing it in a joint way and need to ensure that we bring each other along for the journey … It’s about reframing what we’re doing and Gunaikurnai cultural values informing what we’re doing rather than having this as an afterthought. When it’s all said and done, we’re managing to protect rather than getting permission to cause harm. It’s not understanding cultural values as one area or some artefacts scattered somewhere; the whole landscape has cultural value for us.

Nick Loschiavo – From a design perspective, I think what’s new is non-Aboriginal people listening. What joint management offers us collectively is the ability to listen to Traditional Owners on Country.

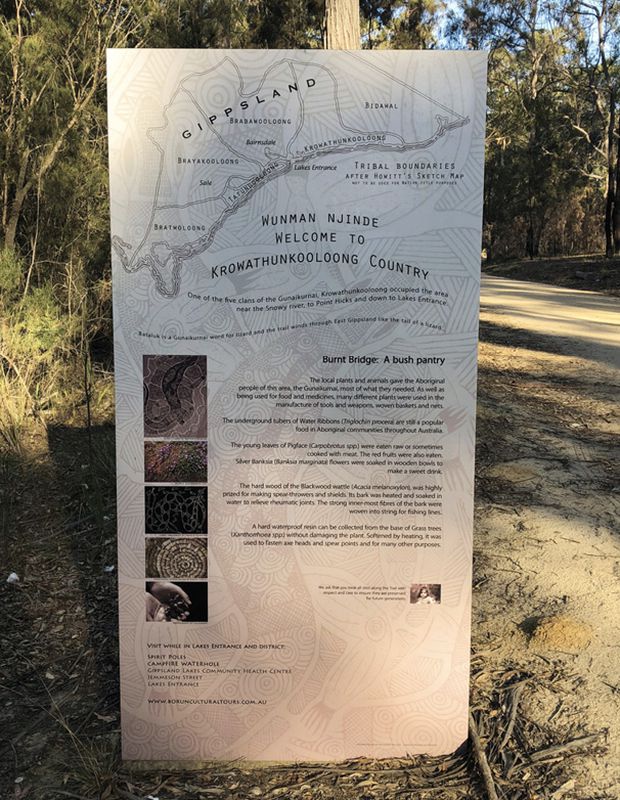

Signage at Lake Tyers State Park values and promotes Gunaikurnai culture and knowledge.

Image: courtesy Parks Victoria and Gunaikurnai Land and Water Aboriginal Corporation

The Glasshouse Camping area in Lake Tyers State Park.

Image: courtesy Parks Victoria and Gunaikurnai Land and Water Aboriginal Corporation

On seeing and understanding landscape as Country:

Nick Loschiavo – A key word that Matt mentioned was “reframing,” which allows Traditional Owners to lead the conversation. Whether we’re designing a bollard or a campground, we understand that the context is Country.

Matt Holland – One of the biggest things is to understand the areas that we’re managing better and what values they have as Country. Some cultural values are known but a lot of Country hasn’t been surveyed or looked at for a long time, so one of the main goals is to do what we’re calling cultural mapping. This involves archaeological surveys (we have a memorandum of understanding with Monash University so we can work together to use their expertise) and working with community to get oral histories.

Nick Loschiavo – The cultural mappings allow us to see what only Traditional Owners are able to see and, hopefully, we can learn. In the form of both the cultural narrative and the language that’s used to describe things, it changes the way we see. And it gives us more meaning in terms of the design response.

Rob Farnham – Identifying what’s in the landscape and its values through the cultural mapping helps us, as Gunaikurnai rangers, to identify what we want to work on and protect within those areas as well.

Matt Holland – One of the big goals in the joint management plan is that the broader community also gains an understanding of the Country that they’re on. We’re doing some other projects around interpretation plans for different parks using the cultural information that has been gathered and generously shared by GLaWAC. It’s about broadening an understanding of the significance of the place that you’re on and understanding what it means to the Gunaikurnai community. Language is a big thing and we try to reintroduce language so we can start to understand places and their significance.

The LTCAS aims to ensure that the values and assets of Lake Tyers State Park are protected and conserved through an equitable partnership between the Victorian Government and GLaWAC.

Image: Rob Willersdorf

On shifts in practice to reflect Gunaikurnai culture, knowledge and leadership:

Rob Farnham – Through joint management, we now get the opportunity to put what we want on Country and in the landscape. We’re getting to the point now where we’re designing stuff on Country and having that opportunity to make decisions on Country first. Changing Country based on how we want it to look empowers myself and this new generation that is going to come through GLaWAC. They get to make these decisions about what happens on Country – I think that’s the most important thing since we got joint management.

Nick Loschiavo – Our responsibility is to the Traditional Owners: understanding the joint management; understanding how they see Country through the cultural mapping; having the conversation on the ground before we do any of the work; having Traditional Owners review the brief in the governance and in the assessments embedded into the project. It’s about working out how we can really partner so that there’s joint management and co-design through every part of the process.

On impacts beyond the management plan’s scope:

Rob Farnham – There’s a lot that happens outside of the nine parks and the one reserve that are currently joint-managed – a lot of training and a lot of work with different stakeholders – because it is still Gunaikurnai Country. And I think it’s now [being recognized] that anything that happens outside of the parks is still on our Country … A lot of the people that we work with might be doing something off one of our parks, but we still get an invite to come across and have input. It’s a great opportunity for our team to get out, to see more of the countryside and to learn on Country as well, rather than just sticking to those 10 parks that we drive in and work in all the time.

Matt Holland – GLaWAC and Rob are working with East Gippsland Shire and other land management agencies, so while they don’t have a specific joint management arrangement with those parties, they’re trying to manage things in a similar way in the sense of that reframing. Hopefully, through the renegotiation of the Recognition and Settlement Agreement, more areas will become joint-managed and that will continue the growth and broader understanding.

Nick Loschiavo – That’s the promise that a joint management plan has: that it bleeds into everything else and that everything relates to Country. Parks Victoria, DELWP, the Catchment Management Authorities, the power authorities, wind farmers – anybody who’s putting in any infrastructure or thinking about planning is starting to look to the joint management plan and Gunaikurnai for guidance.

_

The outcomes achieved by GLaWAC and Parks Victoria over 10 years through shared governance inspire us to imagine what institutional change and its impact might look like in other contexts, as well as the types of relearning landscape architects might need to decentre themselves as authors, shifting their role to support and extend community-led processes.

1. D. Cosgrove, “Prospect, Perspective and the Evolution of the Landscape Idea,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol 10 no 1, 1985, 45.

2. M. Rose, Authors and Owners: The Invention of Copyright ( Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 7.

3. H. Jacobs, “Claiming the Site: Ever evolving social-legal conceptions of ownership and property” in A. Kahn and J. Burns (eds), Site Matters: Strategies for uncertainty through planning and design (Milton, Taylor and Francis Group, 2020), 14.

4. B. Fleming, “Design and the Green New Deal,” Places, 2018.

5. P. Horrigan and M. Bose, “Towards democratic professionalism in landscape architecture” in S. Egoz, K. Jørgensen and D. Ruggeri (eds), Defining Landscape Democracy: A Path to Spatial Justice (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar, 2018), 74.

6. S. Costanza-Chock, Design Justice: Community-led practices to build the worlds we need (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2020), 84.

7. Gunaikurnai Traditional Owner Land Management Board and State of Victoria, Gunaikurnai and Victorian Government Joint Management Plan (Bairnsdale, Vic: Gunaikurnai Traditional Owner Land Management Board, 2018), 30.

Source

Practice

Published online: 28 Feb 2023

Words:

Jen Lynch

Images:

Anne-Marie Pisani,

Rob Willersdorf,

courtesy Parks Victoria and Gunaikurnai Land and Water Aboriginal Corporation

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2023