In September 2017, Moscow’s first new park in more than fifty years was opened. A collaboration between Diller Scofidio and Renfro (DSR), Hargreaves Associates and Citymakers, Zaryadye Park introduces Russia’s four ecological zones of tundra, steppe, forest and wetland into the very heart of Moscow. This strategy of “wild urbanism” is somewhat familiar, sharing similarities with DSR’s treatment (with James Corner Field Operations) for the much-celebrated High Line. Both approaches combine a messy ecology with a flexible paving strategy, blurring the delineation of planting and movement. But any references are quickly forgotten when encountering the constructed park in its extraordinary context.

Zaryadye Park is located on prime Moscow real estate. Next to the famed Red Square, the Moscow River and Kitay-gorod, a cultural and historical area in the city’s centre, the site has attracted monumental architectural visions throughout the twentieth century. Stalin, for example, nominated the site for his eighth monumental skyscraper, only getting as far as laying the foundations. In the 1960s, Khrushchev constructed the brutalist Rossiya Hotel, which remained Europe’s largest hotel until its demolition in 2006. The site was then targeted for commercial development, however, the appointment of Sergey Sobyanin as Moscow mayor in 2010 led to the abandonment of the scheme.

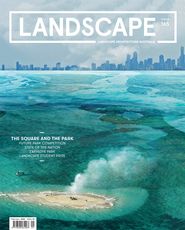

Zaryadye Park occupies a prime urban site abutting the Red Square, neighbouring the cultural precinct of Kitay-gorod and bounded by the Moscow River.

Image: Diller Scofidio and Renfro

Under the guidance of the previous mayor Yury Luzhkov, Moscow had been shaped into a global city through the encouragement of international capital and investment. Sobyanin, elected in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, sought to retain capital and expats, regulate the economy, and offer more organizational and political transparency. A five-year program “Moscow, a city comfortable for life” sought to reposition the capital as a convenient city with a high-quality urban environment.1 These developments were guided by a new generation of western-trained professionals (such as the chief architect of Moscow, Sergey Kuznetsov), open design competitions and collaboration with the Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design, which was founded in 2009 as an independent research institute focusing on urban design and development. Outcomes focused on remodelling Moscow into a more human-centred experience; for instance, construction was limited within the city, open space upgraded, footpaths widened, streets pedestrianized and car parking restricted. A major new park, commissioned through an international design competition, on the now-abandoned commercial redevelopment site, formed a major feature of the strategy.2

Arguably, the most evocative image from the winning competition entry is of the iconic onion-shaped domes of St Basil’s Cathedral, viewed through a forest of birch. This reimagining of the cathedral away from its more familiar Red Square context dramatically evokes the ambition to introduce a forested ecology into Moscow’s inner urban fabric. The reframing of iconic architecture within a landscape ecology is achieved many times throughout the park; the red walls of the Kremlin viewed across a steppe landscape; the monumental Stalin skyscraper (Kotelnicheskaya Embankment Building) viewed across a picturesque wetland; the monastery of Our Lady of the Sign glimpsed across the close-clipped plants of the tundra.

The colourful domes of Moscow’s St Basil’s Cathedral filtered through a grove of silver birch trees in the city’s new Zaryadye Park.

Image: Iwan Baan

Much is made of the spectacular “flying” boomerang-shaped bridge, which projects over the Moscow river and offers impressive views of the waters and surrounds; however, it is the evocative landscape moments that are the real heroes. Achieved through the skilful manipulation of topography (the site falls over twenty-seven metres), ecology and movement, this strategy of visually merging the surrounding architecture into the landscape stops the park from appearing as a sequence of national ecologies, in the manner of a museum or exhibition. They serve as a constant reminder that this is indeed a Russian park.

At just over two years old, the maturity of the park’s plantings is remarkable, the result of extensive research and skill in designing, sourcing and maintaining the different ecological biomes. The planting is viewed as a constant experiment, with a dedicated staff of landscape architects, ecologists and extensive maintenance staff continually reviewing the success of species. Initially 150 species were planted in the park, with that number now increased to over 300. Different soil depths and fertilizing, watering and maintenance regimes are required to keep the diverse forest types, meadows and tundra healthy. Species are already on the move, with succession evident in some parts of the site.

Visitors to the park can immerse themselves in Russia’s four diverse ecological zones of tundra, steppe, forest and wetland.

Image: Iwan Baan

To date, more than 12 million people have visited Zaryadye, including an impressive one million in one month. The majority come in summer, with the park heaving with people during fine weather. However, it has taken time for Moscovites to accept this new wild urbanism. Petr Kudryavtsev from Citymakers highlights that while Moscow has extensive open space, such parks are distinctly cultural. For example, the Gorky Central Park of Culture and Leisure, renovated in 2011, offers over 120 hectares of formal gardens and ponds, various recreational areas, tree promenades and neoclassical pavilions. Further from the city centre, the re-casting of The Exhibition of Achievements of the People’s Economy (VDNKh) into a mixture of exhibition pavilions, gardens, parks and performance spaces contributes an additional 237 hectares of public space.

At just over 10 hectares, Zaryadye Park breaks the formality of these parks, mixing the ecological with the recreational, built form with topography, culture with nature. Submerged into the park’s undulating surface are restaurant pavilions, a media centre, a site museum, a nature centre, along with 430 car parking spots. Presenting a mixture of education and entertainment, this cultural program features a 5D multimedia experience, Flight over Russia, and an immersive ice cave, along with more educational activities such as a Nature Preserve Embassy and exhibition venues. The Zaryadye Concert Hall, constructed on the park’s eastern edge, is the largest architectural program, containing two concert halls which hold around 1,500 and 400 visitors each. From the park, the bulk of the building is hidden under a hill topped with a large crystalline roof structure, open on three sides. With views back to Red Square and the Kremlin, the hill offers a sheltered amphitheatre with seating for 1,500 people, facilitating outdoor performances and free events. For example, on my visit I witnessed an enthusiastic plate painting event for pensioners. Such activities, Kudryavtsev says, are aimed at breaking social isolation by bringing people together.

Zaryadye Concert Hall’s crystalline roof reflects the park’s ambition to provide visitors an all-year-round comfortable microclimate. The hill and the crust were shaped to take advantage of the natural buoyancy of warm air, with the roof providing heating and protection from wind. In summer, parts of the structure can be opened to encourage air circulation, with the option of water misting. The microclimatic potential of the crust is yet to reach its full potential, with more resolution required on the planting of the winter garden and other climatic details.

Emerging from the park’s rolling topography, the crystalline roof of The Zaryadye Concert Hall is designed to offer a comfortable microclimate in all seasons.

Image: Iwan Baan

For the government, Zaryadye is considered a symbol of today’s Russia – a national identity represented through natural and cultural potential. That such a vision was developed by North American designers and achieved at a particularly low point of US–Russian relations is particularly fascinating. I have been following the evolution of the design for many years, visiting the office of DSR in New York in 2016, just as they were about to hand over their proof of concept. At the time, they were unsure how their scheme would be translated by the Russian designers and contractors. DSR architect Brian Tabolt says that in the end, it “was a very positive collaboration” that was “driven by local construction techniques and processes,” but with plenty of opportunities for the original design team to offer “input on maintaining the vision of the project.”

When I visited the project in July 2019, I was surprised by the quality of the park, which has been recognized with numerous design awards, most notably a spot-on Time’s “World’s Greatest Places” listing in 2018. For Hargreaves Associates landscape architect Mary Margaret Jones, the way the park offers “a sense of escape from the city and the ability to explore and discover” is one of its most valuable attributes. “It is a park for the people, and they are embracing it,” she says. “It is immensely gratifying to see so many people enjoying the park and to see the landscape flourishing.”

A “flying” boomerang-shaped bridge extends over the Moscow River, offering expansive panoramas of the skyline and surrounding urban fabric.

Image: Iwan Baan

Critics of the park point to its considerable cost and question whether it is a truly open and democratic space, or is instead operating only to the taste of the Western-oriented middle class.3 However, given the park’s proven popularity, its 24-hour accessibility and spatial openness, these comments are hard to justify. In many ways the park operates in a far more democratic nature than other contemporary parks in Australia, Europe or North America – including the notably tightly controlled New York High Line. This criticism can be applied more broadly to Sobyanin’s neoliberal placemaking which some describe as “hipster Stalinism.”4 While parks and upgraded public domain cannot address broader political dissatisfaction, they can go some way to addressing quality of life. As someone who first experienced a hostile Moscow in the dark days of 1991, an encounter with today’s city is a far more engaging and accessible experience, with increased public activities and civic values evident. On this visit someone even smiled at me on the Moscow metro.

1. Mirjam Budenbender and Daniela Zupan, “The Evolution of Neoliberal Urbanism in Moscow, 1992-2015,” Antipode, vol 49 no 2, 2017, p.294–313.

2. ibid.

3. Kiril Ass “Moscow’s New Clothes: The (in)visible transformation of Russia’s capital under Sergei Sobyanin,” Mayors issue of Topos, 2018, p.70–77

4. Mirjam Budenbender and Daniela Zupan, “The Evolution of Neoliberal Urbanism in Moscow, 1992-2015,” Antipode, vol 49 no 2, 2017, p.294–313.

Source

Review

Published online: 5 May 2020

Words:

Jillian Walliss

Images:

Diller Scofidio and Renfro,

Iwan Baan

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020