When you think of a memorial, what comes to mind? Is it a bronze object or a grand structure inscribed with names, dates and times? Is it a tree or a spot by the shore that gives you the space and time you need for a moment of mindfulness – a moment for reflection? On a leftover green space in busy East Melbourne, the Victorian Family Violence Memorial, designed by Muir and Openwork, is the latter. It is a public yet personal place, shaded and held by landscape. Undefined by icons or objects, the project aims to break preconceived ideas of what a memorial could and should be, allowing anyone and everyone to interpret the space, make it their own and use it for their moment of reflection or healing.

For a small-scale project, the Family Violence Memorial had a relatively long journey from conception to realization. Announced in early 2016 by the Victorian Government and the City of Melbourne, the joint project battled typical processes, protocols and approvals – to be expected with any government project – along with unpredicted changes in ministerial leadership, bringing the momentum of an already slow-moving process to a standstill. After a brief hiatus, extensive consultation and exploration for the appropriate site, the tender began in 2019. Skye Haldane, principal strategic design at City of Melbourne and chair of the city’s Plaques and Memorials Committee, explains: “The brief was quite open [but] it wasn’t about a plonked object, [as that’s] not something we see as a contemporary way to create good public space.”

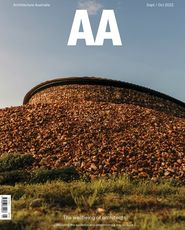

he seated congregation space is oriented to offer views to the Fitzroy Gardens. Sculpture: Taken Not Given (2018) by Anne Ross, in recognition of the state apology for forced adoption policies and practices.

Image: Peter Bennetts

So how does one design a memorial for the complex, immeasurable and hidden crisis that is domestic violence? How can a memorial represent a cause or event that is not a fixed moment in time? For Muir and Openwork, the answer lay in creating a space sculpted by landscape, informed by lived experiences and guided by empathy. At first glance, the project leans more toward public amenity. The site, St Andrews Place Reserve, is reactivated by the memorial’s invitation to sit and occupy. A thin black steel wall curves around the space and guides visitors down concrete decking to a seating area that Openwork’s founder, Mark Jacques, describes as “the room under the elm tree.” From within this space, the memorial starts to reveal itself. A plaque is positioned quietly at one end of the wall, with a co-authored explanation of the memorial’s purpose. The seating orientates the body to the memorial wall, for reflection, and to canopy views of Fitzroy Gardens beyond, for repose.

The potential for incidental engagement by the general public is one of the project’s strengths. Anyone enjoying the space’s seating and outlook might find themselves taking a closer look at the setting, and engaging in a moment of reflection for those impacted by domestic violence – a moment of quiet protest.

The project is understated for a reason. The non-prescriptive nature of the space speaks to the necessity for privacy, something particularly important for victims who are suffering or have suffered. From the conversations I had with collaborators and stakeholders, it was clear that the designers understood this restrained approach, not only because of their participation in 50-plus workshops held by the City of Melbourne, but because of the presence and exercise of empathy.

In the design of the memorial, Muir and Openwork were guided by landscape, empathy and the experience of victim survivors.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Understanding how someone feels – and validating that feeling – is not a tool in the kit of every architect. But for a project like this, a comprehension of the sensitivities and potential triggers – however big or small – was critical to creating a space that is welcoming to all. “[When] we started to get too specific [with the design], we knew we were becoming ex- clusive … and this is not a place for anyone to be excluded,” shares Jennifer Jackson, chair of the Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council.

The memorial is unadorned with imagery or objects, but is layered with meaningful details that have been informed by stories shared through the process. Conversations with Traditional Custodians, along with collaborator Sarah Lynn Rees, manifested in the gift of language. “Ngarru biik marrna Guliny dillbadin – Lore of the land keeps people safe” (Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung) is inscribed on a smoking vessel, grounding the memorial physically and spiritually in Country. The positioning of this vessel was important, as it allows ceremonial smoke to wash over those concluding their procession through the site. The path through the memorial is flanked with perennial planting in shades of purple – the colour associated with ending domestic violence. Landscape and language have been seamlessly choreographed to allow the project’s purpose to be somewhat indistinct yet clear at the same time.

One of the memorial’s greatest successes is its presence. After a long and complex design journey, the space offers those who may feel isolated the opportunity to feel united. A space to be held and heard, its ever-changing yet constant nature allows it to be what Muir calls a “memorial in motion.” This apt concept addresses the complex and continuing issue that is domestic violence. And although the project does not signal the end of violence, it is a gentle call for long-awaited reform.

Credits

- Project

- Victorian Family Violence Memorial

- Architect

- Muir

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Alessandro Castiglioni, Amy Muir, Liz Herbert, Marijke Davey, Mark Jacques, Toby McElwaine

- Landscape architect

- Openwork

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Consultant

Victim Survivors’ Advisory Council

Design, project and stakeholder management, and responsible land manager City of Melbourne

Funding and project delivery oversight, and victim survivors’ stakeholder management Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

Irrigation consultant Ten Buuren Irrigation Designs

Memorial stakeholder Forced Adoption Practices

Structural engineer WSP

Traditional Custodians and cultural advisors Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation, Boon Wurrung Foundation, Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation

- Aboriginal Nation

- Built on the land of the Wurundjeri people of the Kulin nation

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Installations

Source

Review

Published online: 10 Oct 2022

Words:

Georgia Birks

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2022