Harry Howard was the first landscape architect I met. The first landscape project I can recall seeing was the model of Canberra’s High Court of Australia and the National Gallery of Australia, in Howard’s office in McMahons Point, Sydney in 1976.

Howard was part of a group of landscape architects that started the AILA in 1966. This group changed the profession through its practice, drawing together to elevate the profession in Australia. The now-mature Sculpture Garden at the National Gallery of Australia forms a fitting tribute to Howard’s vision, his sense of scale and proportion, his humility and the lightness of his design touch.

The HCA/ANG precinct, as it was titled on the drawings, was many years in the planning and design phase. The key component of the precinct is the Sculpture Garden, now thirty years old. The garden was designed specifically around several sculptures that the inaugural gallery director, James Mollison, had been acquiring since the mid 1970s. The garden is the product of a collaboration between Mollison, architect Col Madigan, Howard and Barbara Buchanan, the project landscape architect. Peter Dalkeith Scott was responsible for the precinct site and landscape works.

Fujiko Nakaya’s fog sculpture generates a fine mist over the marsh pond and surrounding plantings.

Image: Dianna Snape

The Sculpture Garden is one of the few gardens in Canberra that architects get excited about. If you ask architects what their favourite Canberra landscape is, the answer is very often, “The Sculpture Garden at the National Gallery.” This is counterintuitive for me, for here is a landscape that, at least on two sides of the building, dominates the building and creates the space. The brutalist gallery facade is subservient to the canopy of the eucalypts. My choice for the best view in Canberra is that from the National Gallery Members Lounge looking north to the lake, through the canopies of the randomly planted eucalypts. This view matches the hand-drawn presentation images prepared during the design phase in the late 1970s.

In 1994 the Australian Heritage Commission listed the High Court-National Gallery Precinct in its Register of the National Estate (now the Australian Heritage Council’s Commonwealth National Heritage List). The architects for both buildings were Edwards Madigan Torzillo Briggs. Col Madigan was a champion for both buildings and the precinct for many years post completion, until his death in 2011. Howard equally had championed the landscape and the qualities of the original design until his death in 2000. A detailed chronology of the development of the High Court, the National Gallery and the gardens is included within the heritage citation, which describes the precinct as “a highly regarded expression of contemporary architectural and landscape design … a fine example of the newfound idiom of landscape design being practised in Australia at the time, using carefully grouped, local species as informal native plantings against modern architectural elements.”

Dadang Christanto’s Heads from the North (2004) in a marsh pond.

Image: Dianna Snape

In Sculpture Gardens: Australian National Gallery, Canberra, Study 1, Howard outlined his concept for the landscaping, in which he explained “that it would provide physical and psychological comfort allowing visitors to orient themselves and be guided through a sequence of varying ‘gallery’ spaces or rooms. The planting was to comprise only Australian native species and, in particular, those occurring around the Canberra region. The asymmetrical and haphazard character of Australian trees and plants would in time soften the formal architectural principles underpinning the design.”

Howard’s design statement emphasized the use of locally occurring Australian native species, and the design’s “asymmetrical and haphazard character.” Howard was an early convert to the use of indigenous plants in his projects. He was awarded an Australian Institute of Horticulture award for his locally indigenous planting scheme at Helen Street Reserve, Lane Cove, in the late 1970s. He had a series of home nurseries throughout the 1970s, at Sydney’s Wahroonga and then McMahons Point, where he grew local provenance plants. Cedar Wattles Nursery, which Howard ran with Helen McKay, also sold plants to the general public. Needless to say, the species selection and planting layout was an innovation for the national capital. Howard and Buchanan were assisted in the selection of locally indigenous plants by Peter Sutton, a horticulturist employed by the National Capital Development Commission as a landscape manager who was instrumental in the sourcing and trialling of many of the shrub and understorey plantings.

Cones (1982) by Bert Flugelman.

Image: Dianna Snape

Howard’s desire for asymmetry to act as a counterpoint to the prevailing symmetry and order within the Parliamentary Triangle did not weaken. I spoke with him shortly before his death, at the time that the winner of the design competition for Commonwealth Place was announced. Howard had seen an image of the winning design and was very excited about the asymmetry introduced by the proposed planting of trees to one side of the grassed space.

Interestingly, the Sculpture Garden is still the only landscaped space within the Parliamentary Triangle where the trees are not planted to a grid. This space is quite different in character to any other space in the Triangle due to the random patterns and growth of the trees and understorey. The majority of the Parliamentary Triangle presents isolated buildings fringed by regularly spaced trees or blocks of gridded plantings. The landscape space is a void, or negative space formed by the positive edges of the building and the trees. The result is the creation of spaces that perform their ceremonial function of providing long, broad vistas and vast garden rooms, but which dominate the visitor and can be overbearing in Canberra’s extremes of heat and cold, discouraging active use by pedestrians. The Sculpture Garden, by contrast, is a positive spatial volume formed by the trunks and foliage canopies, creating a space that is welcoming. It provides Howard’s “physical and psychological comfort,” which can be absent in other areas of the Parliamentary Triangle.

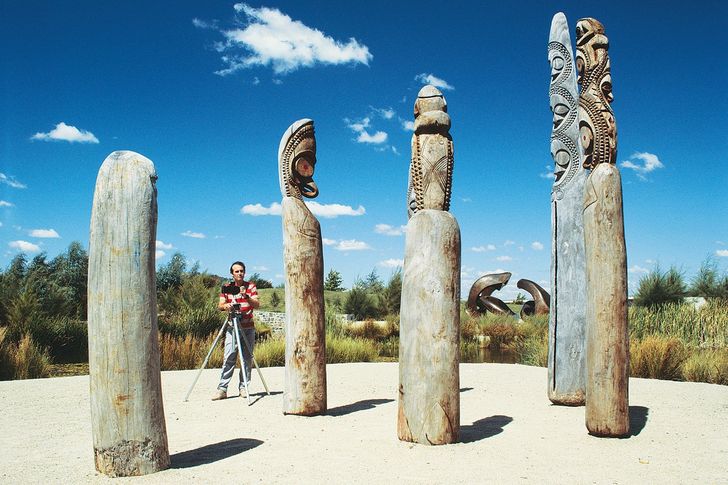

Photos from the 1990s: Slit drums from Vanuatu.

Image: Courtesy National Gallery of Australia

The gallery gardens are now very much a “collection” of landscape architecture. Following the initial Howard/Buchanan construction completed in 1982 was the 1994 Fern Garden designed by artist Fiona Hall, which occupies the courtyard space formed by Andrew Andersons’ temporary exhibition building, completed in 1998. In 2010, the Australian Garden designed by McGregor Coxall was completed. This garden occupies the former southern car park area and includes a Skyspace installation by James Turrell. The garden wraps around the new entrance to the building and provides a broad grassed area that flows from the new function rooms. The planting palette continues to exclusively use indigenous plants. The 2010 building extensions were again designed by Andrew Andersons. The staff parking area has been moved to occupy part of what was to have been the Autumn Garden of the Howard/Buchanan scheme. The Australian Garden received a design award in the 2012 AILA National Awards.

Interestingly, both the Howard/Buchanan Sculpture Garden and the McGregor Coxall scheme had proposed further stages. Significant cuts to the original design were made in the pre-tender phase, and were not reinstated even following favourable tender results. (Disclosure: one of the writer’s earliest drafting projects while still a student was to document the amphitheatre, which was subsequently value-managed out of the project and replaced by grassed embankments.) The McGregor Coxall scheme is very much considered by current gallery director Ron Radford to be “stage one” of the Australian Garden. Stage two – which includes further building and civil works, and which will provide additional underground parking with landscaped podiums – is being designed, but awaits a more favourable Commonwealth funding regime.

Photos from the 1990s: Floating Figure (1927) by Gaston Lachaise.

Image: Courtesy National Gallery of Australia

According to Howard,1 the design objectives for the gardens included “the establishment of a strong visual framework which recognizes the unique lakeshore site and helps the user orientate,” and the creation of “a single sculpture viewed discreetly in an individual setting – there is no feeling of gallery or self-conscious display. The sculpture is a focal point in the landscape, completing the scene.”

A bureaucratic decision in 1975 radically changed the direction of approach to the gallery entrance. It was planned that it would lead to Roger Johnson’s “National Place,” however, with the abandonment of that project, the gallery entrance was left five metres above natural ground level. Later, in 1978, traffic direction on the access road was altered, and a car park was constructed to the south, instead of the larger underground car park that had been planned. This resulted in the majority of visitors approaching the gallery from the rear. The resolution of the “front door” design issue occupied much of the second and third directors’ tenures. Betty Churcher, the second director, attempted to live with the entrance, but made several changes to the internal layout, and was the director during the planning of the Fern Garden and the temporary exhibition annexe. Brian Kennedy, the third director, determined to resolve the front door problem. Plans prepared at the time drew criticism from Madigan, Howard and Buchanan. They were to galvanize support from a number of prominent architects and landscape architects, which culminated in a submission, prepared in 2001, of a statement of principles to protect heritage values, with numerous signatories from members of the professional organizations.

In 1999 Howard and Buchanan prepared a detailed review of the condition of the precinct, measuring the condition against the design intent. Buchanan further reported on the condition in 2000. Details of the key departures from the constructed works related to the outdoor restaurant are as follows:

- The car park and access road built behind the Henry Moore sculpture to service the temporary restaurant, which was not part of the original design, brought cars into a pedestrian zone and intruded into the backdrop to the sculpture.

- The enclosed marquee housing the temporary restaurant blocked visitor circulation around Marsh Pond and prevented visitors other than restaurant clientele from using the lower terrace.

- The angled water channel (part of the Woodward water feature) was covered over in the section that dissects the terrace next to the Marsh Pond.

The report also commented on the general deterioration of the plantings and furniture, and the introduction of miscellaneous items such as concrete paving, bins, signs and drains. A point the report made well was how the concept plan’s design intent had, in nearly all cases, been realized. This was achieved through the planned haphazard development of the multiple, varying angled trunks that make up the canopy and form the landscape architecture that is the garden rooms.

The feeling I take from the now thirty-year-old gardens is one of resilience. The Sculpture Garden has had to battle not only Canberra’s climate, but also its bureaucracy. The garden has struggled against a changing maintenance culture, of public to private, and gallery directors with varying levels of connection and awareness of the physicality of the spaces. There have been few changes over time to the placement of sculptures, and the heritage status can be a double-edged sword. While it was critical in saving the gardens and the gallery from the poorly thought-out proposals to improve the front entrance of the gallery in the late 1990s, the heritage listing complicates changing the sculptural collection.

The fourth and current gallery director, Ron Radford, oversaw the 2010 addition, and the new entrance and the McGregor Coxall Australian Garden. Several new sculptural works were installed in conjunction with the additions, and a new work was installed in the Sculpture Garden. The gallery spent a great deal of time and a large amount of money on a heritage statement to justify the insertion of the (generously donated) maquette, Angel of the North by Antony Gormley, on the axial line through the garden, close to the intersection with the lake. Other newly installed works have been granted “temporary works” approval, and require new applications on an annual basis. Radford wonders aloud whether all future works should be termed “temporary” to allow them to be moved outside the strictures of heritage requirements.

The garden is a true representation of the designers’ intent, and the light hand of the designers is evident in the soft quality of the light and absence of hard edges to the spaces. It is a testament to the skill of Harry Howard and Barbara Buchanan, and also that of Peter Sutton, the City Parks manager responsible for the maintenance of the precinct during the initial establishment of the gardens.

1 Harry Howard, “Landscaping of the High Court of Australia and the Australian National Gallery – the Sculpture Gardens,” Landscape Australia, 3/82, August 1982, 208–215.

Source

Report

Published online: 1 Nov 2017

Words:

Neil Hobbs

Images:

Courtesy National Gallery of Australia,

Dianna Snape

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2013