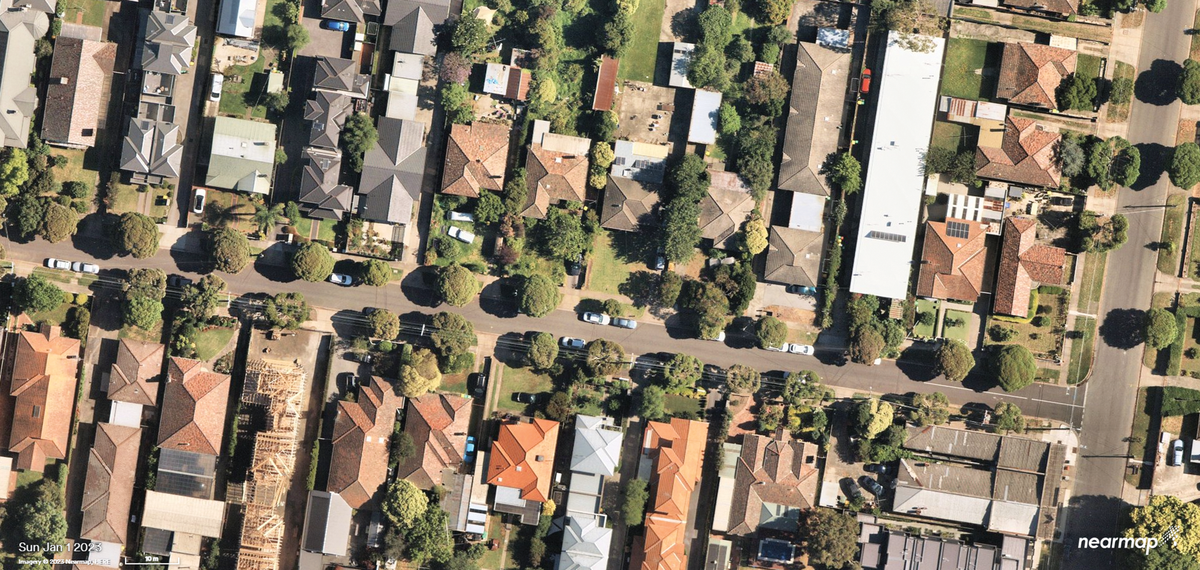

Cities across Australia have been trying to reverse the trend of urban sprawl by densifying. In Melbourne this is being enacted through the principle of the “20-minute neighbourhood.”1 The “middle belt” areas – those between 10 and 20 kilometres from the CBD – that are well serviced by public transport are the site of rapid and intense densification. Reservoir, the suburb where I live, is one of those development hotspots. Although the logic of increasing density in my suburb makes sense, what happens to the suburban ecology? And can small interventions make a meaningful ecological difference? First, two questions need to be posed: what organisms can be found in the suburban ecological matrix, and what ecological significance do they have?

The design of small courtyards of infill development can play meaningful roles in suburban ecology when they include biological water and topographical diversity.

Image: NearMap

Suburbs could be viewed as ecological refugia, especially in times of extreme climatic cycles and unpredictable weather events, which are becoming more common as a result of climate change. In his seminal text The New Nature, Tim Low provides multiple examples of ecologically significant species that now live in urban, suburban and industrial zones, such as the green and golden bell frog (Litoria aurea) discovered in a flooded Homebush Bay quarry during the development of the site for the 2000 Olympics. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists these frogs as vulnerable, partially due to their susceptibility to the chytrid Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis.2 The contaminated water of the quarry is hostile to the chytrid, enabling the frogs to thrive.

Other native animals, such as the common brushtail possum Trichosurus vulpecula, have greater population densities in suburbs than in bushland. For example, City of Melbourne park surveys have shown up to 15 possums per hectare – but only 1–3 brushtail possums share a single hectare in natural environments.3 Possum populations living in remnant bushland in Melbourne’s suburbs are directly influenced by the resources available in the 100-metre radius of houses and gardens adjacent to the bushland. This is because of the abundance of resources and habitat: the highly varied, complex biotic and abiotic structures of suburbia.4 The corella, or Cacatua (Licmetis) tenuirostris, is another species that is thriving in Melbourne’s suburban ecologies. Corellas were observed digging up myrnong daisy (Microseris lanceolata) tubers by colonists in the 1830s; this food source was soon eradicated by land modification and sheep grazing, which pushed corellas to the brink of local extinction by the 1840s. By the 1950s, the birds had adapted to eating a large range of exotic species, such as onion grass (Romulea rosea), commonly found in suburban gardens; their population in suburban Melbourne has been on the rise ever since.5 Every morning I wake to the sound of huge flocks of these birds flying over my house.

So, if suburban ecologies have value but densification is necessary to stop urban sprawl and the destruction of remnant ecologies and food production land, what can landscape architects do to tackle this conundrum? The first design idea I want to discuss is the introduction of biological water. I define biological water for the purposes of this article as a body of water that is allowed to contain life, as opposed to a chlorinated swimming pool or water feature.

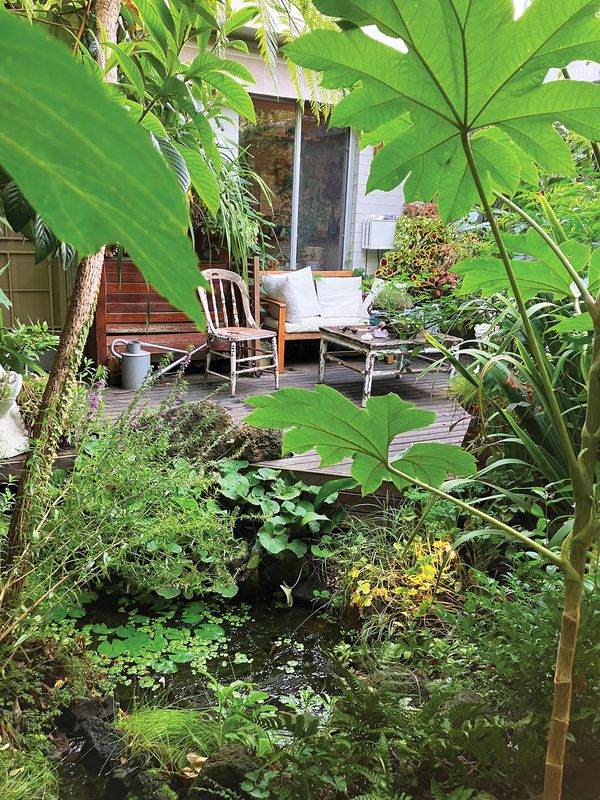

Two ponds and a birdbath have brought microclimates, habitat niches and more than 300 different species to the author’s home garden.

Image: Alistair Kirkpatrick

Take my own garden as a case study. It measures only 70 square metres, which is only slightly larger than many courtyards in new developments. The courtyard sizes of the multiresidential developments in Reservoir are dictated by the planning regulation offsets, which require buildings to be constructed 10 metres from the footpath, which in turn results in front gardens of roughly 60–70 square metres. When I moved in five years ago, my garden had 10 different species of plants, which I estimate is the average level of vegetative diversity in courtyard gardens in my area. I have ascertained this average from my extensive observations during pandemic lockdowns.

When I moved into my garden, the fences were devoid of vegetation, and there was no biological water in the garden. The only birds that visited were a family of ravens (Corvus coronoides) that spent time in the snow-in-summer tree (Melaleuca linarifolia) planted in the street. There were virtually no insects. One of the first things I did in the garden was to build two ponds and install a birdbath. The reaction from insects, birds and amphibians was almost instantaneous; within weeks, I had species I had never seen inhabiting my garden. I had predicted this would be the case, having built ponds at every property I’d rented and, every time, irrespective of the suburb, seen this phenomenal biological activation.

I have observed an abundance of Australian hover flies (multiple species in the family Syrphidae) since introducing biological water. Hover flies are critically important pollinators – without them, we would most likely face extreme food shortages – but they need water bodies to complete their life cycle. With global insect populations in decline, we need to engage every strategy to assist insect populations.6

At the author’s house, fences are covered with vegetation, providing an abundance of food and habitat for native species.

Image: Alistair Kirkpatrick

Complexity, messiness and diversity is the second concept I want to discuss. As previously stated, when I moved in, my courtyard contained 10 different plant species. My neighbours’ front garden currently has seven. At last count, I had 300 different species in my garden, including trees, climbers, epiphytes, shrubs, herbs, forbs, graminoids and geophytes both native and exotic. All of my fences are covered with vegetation, and there is an abundance of food and habitat. There is now topographic variation across the garden that has, in turn, created microclimates and habitat niches. Topographic diversity is critical as it creates a variety of environmental conditions. A good example are gilgais, which are created when reactive clays shrink and swell as a result of fluctuating moisture levels, creating small mounds and depressions. This leads to a range of micro-conditions, such as hot and dry north-west-facing slopes and temporal wetlands, which in turn lead to an incredible diversity of vegetation.7 During heatwaves, my garden acts as a refuge, providing shade and clean water. Last summer, I conducted a comparative temperature measurement, and my garden was five degrees cooler than the surrounding landscape.

What does this have to do with landscape architecture?

Designers, including landscape architects, have a huge influence on garden fashions and trends – think of the cerulean-blue jumper scene from the movie The Devil Wears Prada. In my opinion, the practice of landscape architecture in the last 30 years has been heavily focused on structural design, minimalism and hardscape. I think we need a radical shift towards maximalism, not as an aesthetic movement but as a critical ecological movement. Joan Nassauer discussed the importance of embracing and promoting complexity, messiness and diversity in 1995 with her seminal paper “Messy ecosystems, orderly frames,” which explores design techniques such as manipulating the landscape adjacent to wild spaces into landscape forms that were recognizable to the public as being modified and maintained – and, as such, as having value.8 This could be in the form of boardwalks, fences, mown perimeters – anything that shows the hand of humans immediately canonizes the landscape that it surrounds. These cues can equally be applied to small spaces and large spaces. Small courtyards of infill developments, I believe, can play a meaningful role in suburban ecology, but they need to be abundant, complex spaces full of biological water and topographic diversities. As a profession, we need to be advocating for and promoting the creation of these kinds of spaces – as a matter of urgency rather than as a suggestion.

1.“20-minute neighbourhoods program,” Victoria State Government Department of Transport and Planning, 2 November 2022, planning.vic.gov.au/latest-news/20-minute-neighbourhoods-program (accessed 4 April 2023).

2.Tim Low, The New Nature: Winners and Losers in Wild Australia (Melbourne: Penguin Books Australia, 2017).

3.“Humans and wildlife,” City of Melbourne, 2023, melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/greening-the-city/urban-nature/Pages/humans-wildlife.aspx (accessed 4 April 2023).

4.Michael J. Harper et al., “Resources at the landscape scale influence possum abundance,” Austral Ecology, vol. 33, no. 3, May 2008, 243–252; doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01689.x.

5.“The corrella’s comeback,” Australian Geographic, 6 March 2018, australiangeographic.com.au/topics/wildlife/2018/03/the-comeback-corella (accessed 3 April 2023).

6.Toby Doyle et al., “Pollination by hoverflies in the Anthropocene,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 287, no. 1927, 27 May 2020; doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2020.0508.

7.T. R. Paton, “Origin and terminology for gilgai in Australia,” Geoderma, vol 11, no 3, May 1974, 221–242; doi.org/10.1016/0016-7061(74)90019-6.

8.Joan Iverson Nassauer, “Messy ecosystems, orderly frames,” Landscape Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, Fall 1995, 161–170.

Source

Practice

Published online: 13 Sep 2023

Words:

Alistair Kirkpatrick

Images:

Alistair Kirkpatrick,

NearMap

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2023