A key but neglected urban waterway that runs from the northern ranges of San Bruno Mountain all the way to the San Francisco Bay, Colma Creek has occupied a central place in the area’s history. Building upon earlier work from the Bay Area: Resilient by Design competition, Hassell has been exploring future possibilities for the creek and the city to reduce flooding impacts, strengthen resilience to sea level rise and reverse the area’s real and symbolic separation from the water by restoring public access, returning native species to the area and expanding the number of parks and open spaces. The work has included the recent release of the Colma Creek Adaptation Planning report, a public document that offers a vibrant series of visions for the transformation of the creek corridor.

Hassell principal Richard Mullane and landscape architect Ella Gauci-Seddon spoke with Landscape Architecture Australia’s Emily Wong about how the practice has been working with communities to envision climate adaptive futures for the Bay Area.

Emily Wong: The foundational research for the project came through the Resilient by Design initiative – what was some of the groundwork you undertook that’s informed the report?

Richard Mullane: The first six months of research and site analysis [for Resilient by Design] was about defining a project that was an exemplar of the challenges and solutions for the region. That involved touring some of the most vulnerable locations around the bay – there are nine counties and about a hundred cities, and each week we’d look at one area and tour around 20 to 30 different sites, with local cities and community groups telling us their ideas for adapting their communities to climate change and the liveability challenges they were facing. We found there was a very strong industrial history in the most vulnerable locations, often old port communities with high unemployment, that had been abandoned as the region had turned towards a more service-based economy and the tech sectors.

EW: Is this where the creek concept originated?

RM: Colma Creek is the centre of the plan because it’s a source of flooding, includes marshland and is a centre of the community. There are some really amazing stories from local residents of what the creek had been like many years ago, walking along the shore, and fishing and swimming in the bay – so thinking about what it could be. Our intent was to try and keep the interface between the public realm and the creek corridor in such a way that the people can still see the creek, and the flood solution isn’t massive walls. What we’re doing to the channel maybe doesn’t change the way it functions in normal flooding or day-to-day, but it enhances and reduces the larger flood events.

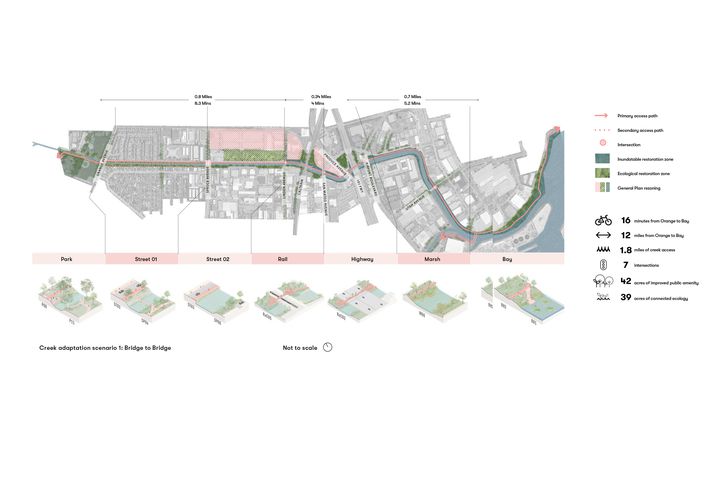

The varied existing conditions and contexts of Colma Creek, from park and street through to marsh and bay.

Image: Hassell

EW: How did the community engagement process work?

RM: We didn’t have a Hassell studio here at the time, so we took over an empty building in the community and made a drop-in centre in the storefront with some trestles and old doors for desks. Our aim was to get out and talk to the community and get them to understand the role the creek plays and the value of the project.

Ella Gauci-Seddon: In Australia we do a lot of, “well here are the options, help us choose which one.” The process here was much more about getting the community involved and bringing them on the journey, so that they feel like their voices are actually heard. The storefront was really important in terms of asking the community, “tell us what you know about this place,” which was what really drove Colma Creek being the centre.

A native plants day held at Mission Blue Nursery as part of the project’s program of local community engagement and outreach.

Image: Hassell

EW: And then the lockdowns happened, quite early on. How did you adapt?

EGS: When we couldn’t host events anymore, we turned the principal diagrams we had created into an accessible children’s book, which was less about, “do you like this option?” and more about, “does this vision resonate with you?” The storybook and the drawings were directly tied into our design process. The book takes a lot of the detail that might be lost or wasted in a normal report – a particular species of frogs or space for snakes under a boardwalk – and celebrates it, and that book became the main avenue for communicating with the community, as well as through Instagram and Facebook.

EW: How does the adaptation planning report engage with the different conditions along the creek corridor?

EGS: We knew from the start that there was a range of sectional conditions, in addition to the flood levels. So, we cut sections to see where the flood levels were, then looked more closely at what was in them and their relationship to adjacent conditions – the public land alongside and the surrounding streets. This became 13 key sections and a long section that understands how the site transitions from a channelized cross section at Orange Memorial Park to a wide and soft-bottomed creek, before entering the bay. The relationship to the surrounding conditions was really important. We condensed these 13 sections back into five key character zones – the park, the street, the knot where all of the rail and roads came together, and then the marsh and bay. It was a process of going from section back to plan, back to section, expanding the number of conditions that we looked at and then condensing them back to an understandable group of types.

EW: Did you look at both public and private land?

RM: The report only looks at public lands because when you’re dealing with a city that has a population of 60,000 people, they are excited but also asking, how are you going to pay for and deliver that? The city didn’t want to freak out residents by showing inundation or land use change – or retreat from the edge of the creek.

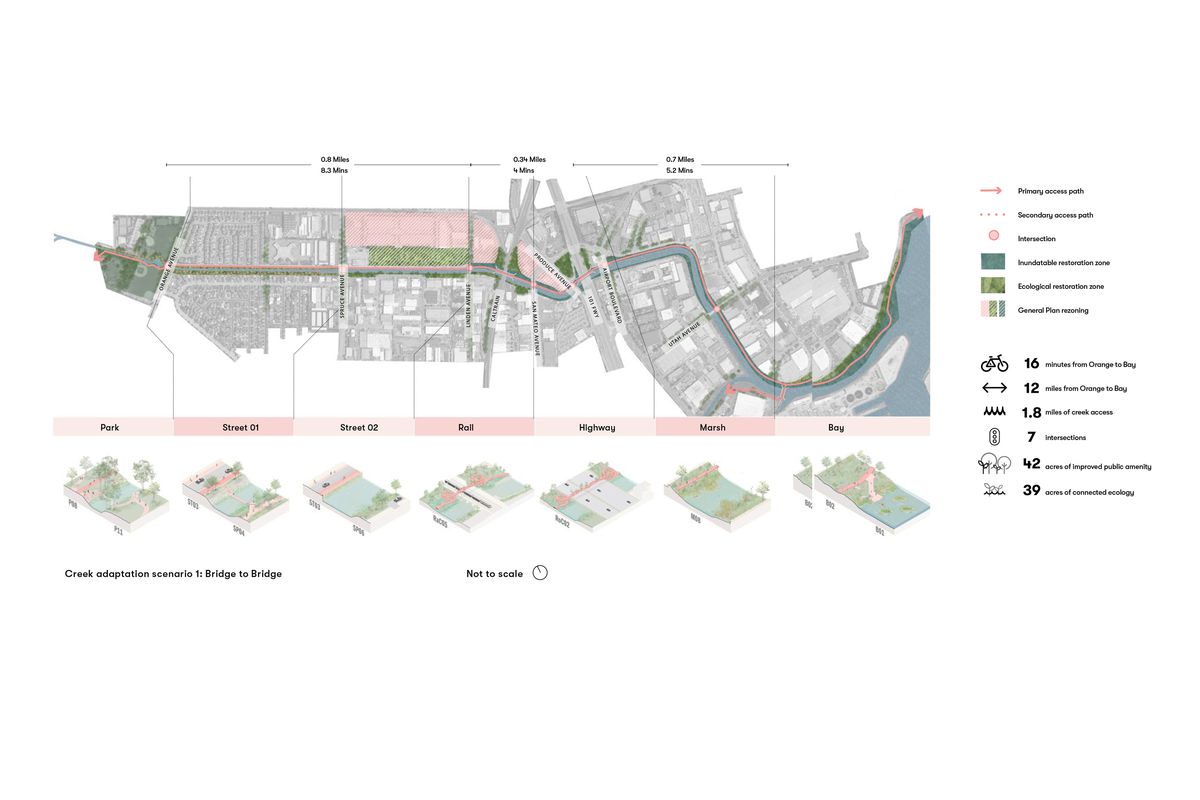

EW: Could you talk about the importance of the “adaptation toolkit” that’s included in the report?

RM: We knew that the conditions we were seeing along the creek were reflective of conditions that existed around the broader Bay Area, so by refining the creek corridor down to the five key character types, with an associated scenario and array of options, we could make the report and ideas applicable to these areas as well. The report is about options, which are really expansive and that actually made the design process easier. Our client, all these agencies, is not that familiar with design, so we can say, hey we’re not putting up option A or B, we’re just saying you’ve got all of these choices – but now we need to decide how you assess what the right choice is to make.

Adaptation scenario options showing possibilities for the creek’s character types of park (left) and street (right).

Image: Hassell

The strategy imagines a restored ecotone and expanded tidal and flood zone along a forgotten corridor of marsh, before the creek enters the bay.

Image: Hassell

EW: The project outlines three key objectives around managing flooding and sea level rise, restoring ecology and getting public access along the water. How did you approach balancing those objectives across the site?

EGS: Each of the character types has a toolkit and scenario associated with it that looks at that balancing act. Some push one aspect or another, but all strive to incorporate all three. All the options are ranked against the project criteria and the principles – for each objective there were two rating types. For example, with ecology we looked at how we could improve access and how people as well as the actual element that we were looking at.

EW: The report focuses on a three-kilometre-section of the creek, but I understand you’re aiming to look at other sections as part of long-term planning for the area. How’s this progressing?

RM: We’re working on the next stage of navigating the grant system. In a recent ballot measure for the Bay Area, two-thirds of residents supported taxing every property to contribute to wetlands and shoreline restoration and water treatment, green infrastructure. This only applies to the tidal sections of the creek, but we’ve put in a pre-application for funding and are talking with the San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority that oversees that. Funding sources here tend to be very focused on one [objective], whereas this is a multi-benefit project – so navigating that is a bit of a challenge. Ideally, in the next stage though, we would be looking to engage half of the creek that the report explores, from the freeway to the bay, looking at areas where we might widen it to create tidal marsh zones and transitional habitats for specific Bay Area species.

A scenario depicting a potentially continuous route between Orange Memorial Park (left) and San Francisco Bay (right) along the creek. The scenario applies adaptation options to each character area of the creek, prioritizing outcomes with multiple benefits.

Image: Hassell

EW: What’s your sense of the direction in the US at this time with respect to landscape architecture and public realm projects?

RM: Generally, until recently, there was a lot of funding toward resilience projects and additional funding towards projects involving restoration on the ground. Unfortunately, this is really drying up now, because the pandemic just hit local and state governments so hard. That said, I don’t think people have valued parks as much before as they do right now. The equity issues around open space and the like are so much more evident now, because of who has and hasn’t had access to parks within walking distance.

Credits

- Project

- Colma Creek Connector

- Design practice

- Hassell

Australia

- Project Team

- Richard Mullane, Ella Gauci-Seddon, Sharon Wright, Dion Gery, Chloe Walsh, Jennifer Gonzalez, Chris Chesters

- Consultants

-

Community engagement consultant

Civic Edge Consulting

Ecology and hydrology consultant E2 Design Lab

Traffic engineer CHS Consulting Group

- Site Details

-

Site type

Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Proposed

Design, documentation 6 months

Category Landscape / urban

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Bay Area Regional Collaborative (BARC), San Mateo County and City of South San Francisco

Source

Practice

Published online: 22 May 2021

Words:

Emily Wong

Images:

Hassell

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2021