During his tenure as prime minister from 1996 to 2007, John Howard was intent on stimulating discussion to define Australian identity. This culminated in what commentators referred to as the “culture wars” – public debates over interpretations of the British colonization of Australia. Projects for Perth’s waterfront, conceived in the lead-up to this period constitute both responses to Australia’s contested history and identity, as well as “symbolic pointers to what was taking place in the psyche” of European Australian society.1 By virtue of the way they symbolize nature, the projects question how European Australian culture relates to Australia’s landscape and Indigenous culture.

Perth waterfront schemes in the 1990s

In the 1990s, Perth’s foreshore – a vacuous greenbelt “reclaimed” from the river in the twentieth century – was the site of many proposals for Indigenous cultural centres, commemorative artworks and walking trails – as well as rallies and protests to recognise Indigenous custodianship of key sites. The river’s edges became the landscape where European Australian culture attempted symbolic reparation for the manner in which they have dealt with the area’s Noongar people over the past two centuries – a manner that has included suppression, murder, theft of land, imprisonment, the imposition of curfews, apartheid, the desecration of sacred sites, religious conversion and so-called acts of “charity.” While much of the planning that took place during this period failed to manifest as major built projects, public artworks celebrating Indigenous culture from this period can still be observed.

In 1991, Perth’s foreshore became the site of the Perth Foreshore International Urban Design Competition. An analysis of entries for the competition reveals a dominant narrative for the foreshore (with exceptions, of course). Many designers conceived of the foreshore as a symbolic vestige of the Swan River’s endemic landscape with competition proposals that attempted to “indigenize” the foreshore with endemic vegetation (in preference to its existing exotic plantings and turf), the re-routing of vehicles away from the river’s edge, the retracing of the river’s original shorelines and symbolic references to Indigenous culture. In short, the designs saw the return of many elements, such as the Swan River’s Indigenous history and messy ecology, which planners had repressed in the reclaiming of land from the river earlier that century.

In broader terms, these proposals reflected the cultural shifts that characterized Australian postmodernity, including a greater respect for Indigenous culture and landscapes. A number of the schemes for the 1991 Perth foreshore competition reflect the then growing realization that the successful conquering of a foreign land, in material terms, does not equate to the conquering of the spirit of the land. From this perspective, Indigenous culture holds the keys to the spirit of the land, a spirit from which the colonizing culture is estranged.2 This situation is acknowledged, albeit clumsily and superficially, in several competition proposals that include forms inspired by Waugal (an Indigenous spirit of creation) and fictional “Indigenous” place names.

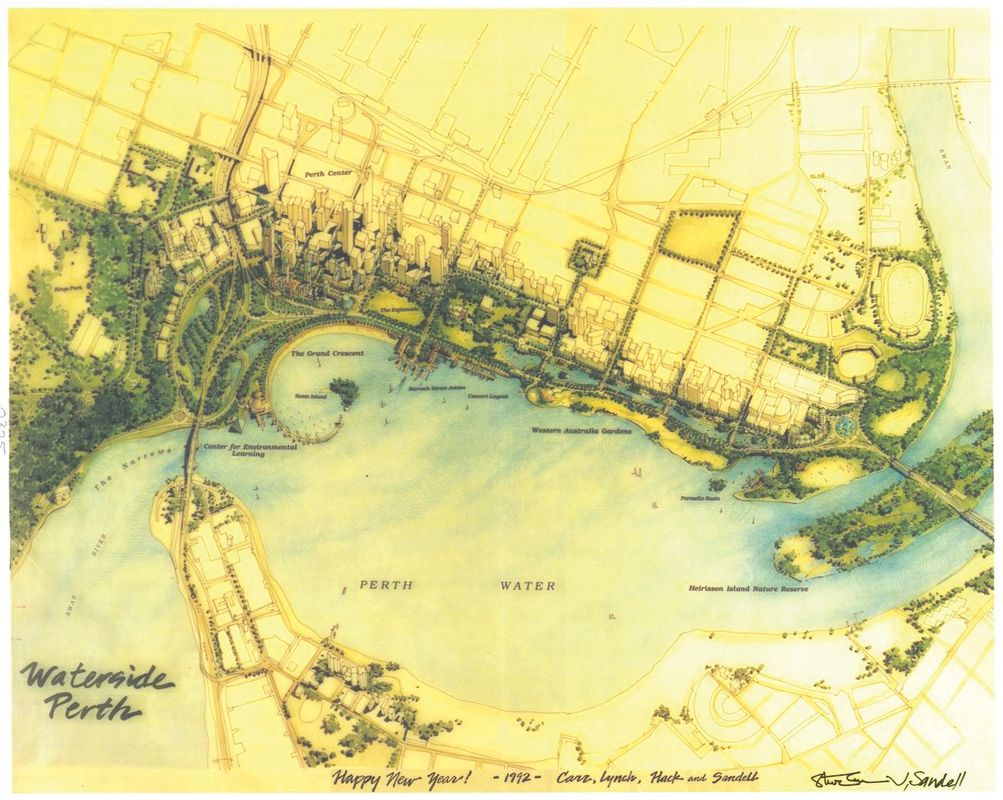

The competition’s winning submission, “Waterside Perth,” produced, somewhat ironically, by the Massachusetts-based firm Carr, Lynch, Hack and Sandell, resonated with these themes. Waterside Perth proposed a “harmonious flow from east to west,” starting with natural riverine landscape on Heirisson Island, concluding with an impressive curving jetty, the “Grand Crescent,” and including a “Swan Island” nesting area for the local black swans. The city’s major Riverside Drive was reconfigured into a series of sweeping curves with extensive tree planting. In addressing the perceived disconnection between the city and the river, the design team proposed to excavate a significant section of Langley Park (the expansive grassy open space running alongside Riverside Drive) along the river’s original shoreline, to create the “Old Shore Creek,” turning the remainder of the park into an island.

Waterside Perth, the winning scheme of the 1991 Perth Foreshore International Urban Design Competition.

While it was popular with the public, who strongly supported a naturalistic river foreshore3, ultimately, contractual problems “undid” the Waterside Perth competition-winning scheme. In 1993, the newly elected Liberal-National government ousted the Labor government and abandoned the scheme. Despite lack of state government support for Waterside Perth, a number of related but isolated projects emerged in the following period. These include the Conference Centre and The Bell Tower, both located along the foreshore – neither of which the public regard favourably. Finally, in 2012, an urban conception of the foreshore – Elizabeth Quay – eventually trumped the “indigenization” of the foreshore proposed in Waterside Perth and many of the other 1991 competition schemes.

Unfinished business (2019 onward)

Nonetheless, the themes raised by schemes from the 1990s persist. While proponents of Elizabeth Quay view it as an endpoint for rethinking the foreshore, the three hundred metres of river’s edge redeveloped for the project represents only a small fraction of the eight kilometres of shoreline that comprises Perth Water, a section of the river on the CBD’s southern edge. Policymakers and planners will need to rethink these river edges with respect to climate change, sea level rise and increased-intensity storm events. In relation to Perth Water, mapping of the 1.1-metre sea level rise predicted to have occurred by 2100 shows Langley Park, Heirisson Island and the South Perth foreshores almost completely underwater. Ironically, and not surprisingly, those areas that the city reclaimed from the river for public open space in the twentieth century are most at risk. Moreover, with continued growth in emissions, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has projected a rise of as much as seven metres by 2500. In time, the bulk of Perth’s foreshore “front garden” will be “reclaimed” by the river; possibly reverting back to a pre-settlement landscape of rush beds and salt marshes (albeit interspersed with ruined buildings). Waterside Perth and its excavated canal was a premonition of this future condition.

In time the bulk of Perth’s foreshore “front garden” will be “reclaimed” by the river, reverting a pre-settlement landscape of rush beds and salt marshes.

Image: courtesy Julian Bolleter

True reclamation

This “reclamation” (in the true sense of the word) of land by the river carries a powerful symbolic load. Perth’s wetlands were, and to a degree still are, perceived by European Australia as representative of the “other:” in particular the unconscious and Indigenous culture. Sea level rise and the subsequent unshackling of the river from its river-wall straitjacket is ominous. Academic David Tacey explains a shift occurring in Australian culture which has parallels with this emerging situation: “We have denied the true spirit of the land and its indigenous inhabitants for two hundred years of white settlement – and now the repressed is coming back to haunt us.”4

While not wanting to draw too direct a connection between the Waugal and the monsters of fairy tales, there are some thematic links here. Indeed, Indigenous elders describe the Waugal as a spirit that is responsible for punishing wrongdoers through illness or even death. At one level, European Australian culture has historically denied, repressed and degraded the river that was the lifeblood of the region and a powerful expression of Noongar spirituality. The reassertion of the river’s power – its growing “monstrous” – is, from a certain perspective, a powerful reminder of our collective neglect and wrongdoing.

Noongar academic Len Collard has suggested that former Perth mayor Lisa Scaffidi’s idea for a “statue of liberty for Perth Water” should be Yagan (a Noongar warrior decapitated by white settlers) standing in the river with no head.

Image: courtesy Julian Bolleter

While in the twentieth century, European Australian society was able to reshape the Swan River to reflect its own desires for handsome foreshore parks, in the twenty-first century (and beyond) the river will reassert its ability to shape the city – something schemes for Perth’s foreshore in the 1990s anticipated. This humbling situation for a colonial culture may give birth to a deeper, more meaningful relationship with Australia’s landscape and Indigenous people. Perhaps through this process, new doors will open, inviting a fresh form of consciousness to emerge.

This article has been adapted from the book Take me to the river: The story of Perth’s foreshore, Julian Bolleter, Perth, University of Western Australia Publishing, 2015.

1. David Tacey, Edge of the sacred: Jung, psyche, earth, Einsiedeln, Switzerland, Daimon Verlag, 2009

2. ibid.

3. City of Perth, Central Perth Foreshore Study: Interim Report, 1985

4. David Tacey, Edge of the sacred: Jung, psyche, earth, Einsiedeln, Switzerland, Daimon Verlag, 2009

Source

Review

Published online: 8 Apr 2020

Words:

Julian Bolleter

Images:

courtesy Julian Bolleter

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020