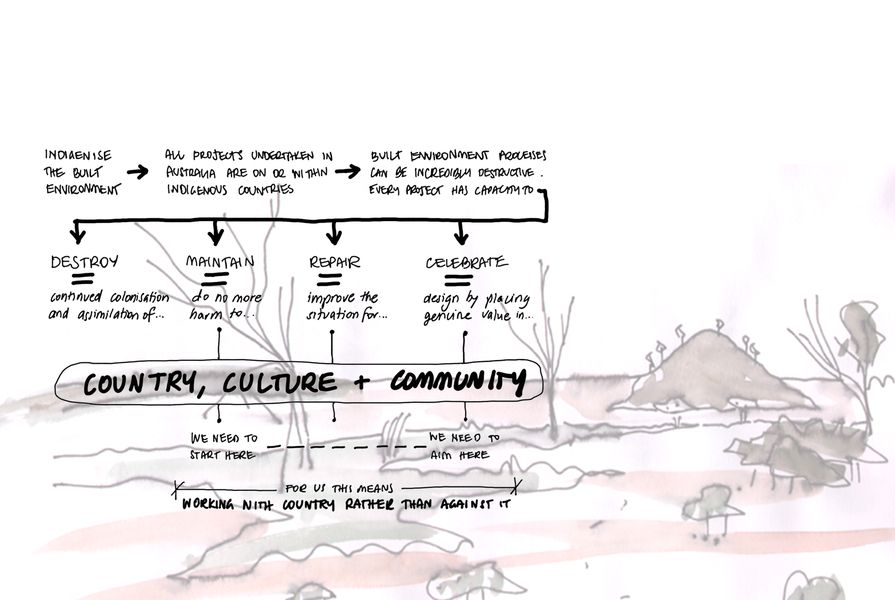

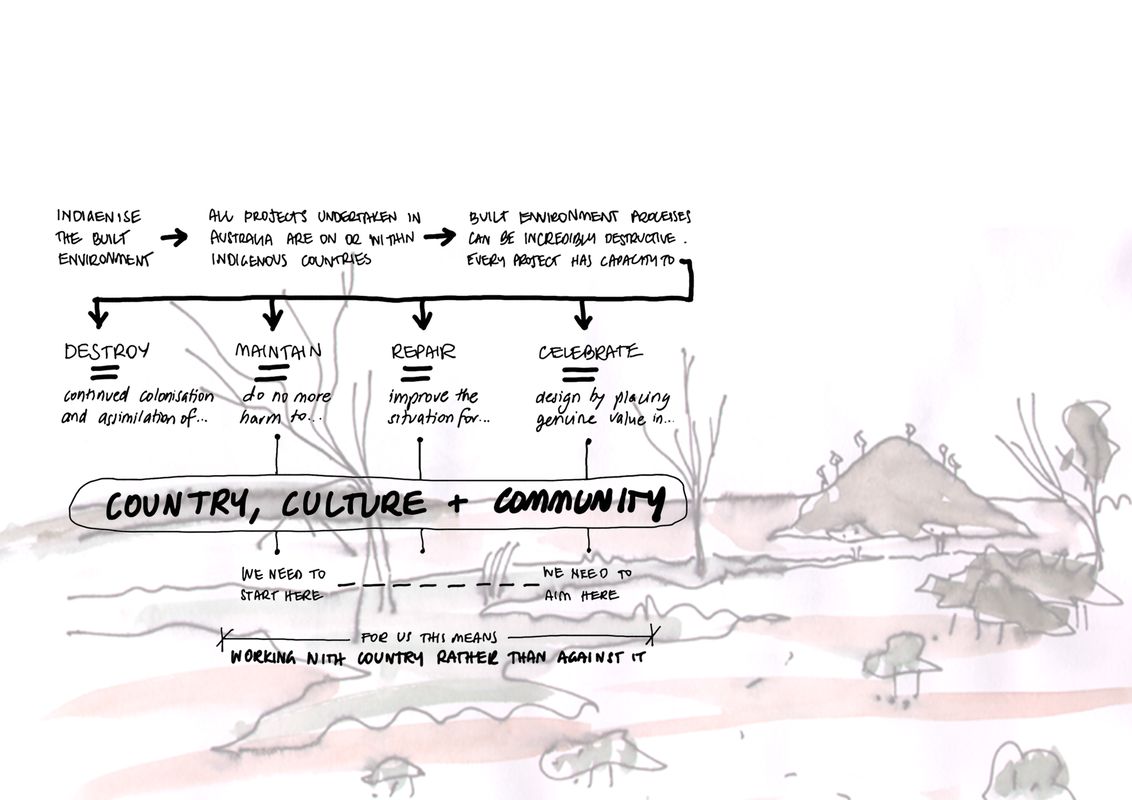

Many of the projects that built-environment practitioners will undertake in their careers will have a direct impact on Indigenous peoples, and every project will have an impact on the Country it resides within. Built-environment practitioners have the capacity to create places that improve the lives of all living beings and to make stronger connections with an Indigenous worldview via a genuine engagement process.

However, not every project can engage with the appropriate Indigenous representatives, and the scope of possible engagement is often dependent on the procurement process established prior to an architect’s involvement. And even where Indigenous engagement has been undertaken, it is too often not reflected in the way the project is articulated in the media. At the very least, for any project, we should acknowledge the Country on and within which it resides. For projects that engaged with Indigenous Peoples, it should also be acknowledged that the work would not exist in its final form without the time, Knowledge and expertise of the Indigenous representatives who contributed. Without this acknowledgement, the public documentation of the project could be perceived as an appropriation of Indigenous Knowledge.

While acknowledgement is important, in order to show true respect, we need to move beyond acknowledgement to document the processes, relationships and outcomes of the project, preferably by centralizing the Indigenous voices that contributed. This requires a shift away from a more traditional, marketing-based approach and starts with a series of fundamental questions about the article you are writing: Why is it being written? Whom does it benefit? Whose voices does it represent? Can it contribute to a wider understanding of Indigenous architecture and process?

Indigenous people and communities have been the subject of endless studies, research papers, projects and books, with the majority written by non-Indigenous authors. For many of these authors, their purpose is to further the understanding of our shared journey; but others write with a view to benefiting themselves or the institution that commissioned the article. Communities frequently comment on how people come, learn and take information away, leaving nothing in return. In writing about built-environment projects, we need to ensure that we are not further exploiting Indigenous communities for personal, commercial or institutional gain.

The following points provide a starting place for writing about projects that were undertaken with Indigenous peoples. Of course, as architects, we work within a broad spectrum of project types, procurement and engagement processes, and community nuances, and not every point given here will be relevant in all circumstances, nor does this list cover everything that might need to be considered. However, all projects impact on Country and therefore on community either directly or indirectly, depending on their use and/or intent. Architects have a responsibility to act ethically in the representation of their projects. The best course of action is almost always to centralize the voices of Indigenous representatives and to act in alignment with the permissions that have been granted to you. To achieve this, you need to have conversations with Indigenous clients, stakeholders and end users (herein referred to as “Indigenous representatives”).

When documenting an Indigenous project:

1. Centre the Indigenous voices involved in the project.

a) Consider co-authoring an article with Indigenous representatives, if appropriate.

b) Where this is not possible, provide a copy of your writing to the Indigenous representatives and ask whether they would be happy to contribute to the piece. Where possible, offer to compensate them for their time. If compensation is not possible, make this clear with your request.

c) Ensure that you allow enough time for the Indigenous representatives to review and respond before your deadline. Note that many communities have internal governance structures that might require approval from Eldership or a board, and the schedule of these processes will not change for your deadlines.

2. Ensure that the writing appropriately represents the community.

a) As noted previously, the most appropriate way for a community to be represented is with their own voice.

b) Do not attempt to speak on behalf of the community.

c) In the context of the project, be sensitive to your own privileged role and the insights that it brings. Know that the short time you spent in/with the community in no way reveals all of its subtle relationships, histories and aspirations. Remember that not everything that may have been shared with you is appropriate to publish – certainly not without permission – and it is not your role to be a commentator on community matters.

d) Be aware that misrepresentation and misidentification can cause harm to and within a community. Check any representation, identification or description of the community within your writing with an authorized community representative. 1

e) If none of the above is feasible or possible, echo the general descriptions and language written by the community in their own media representations (web pages, social media posts, etc.)

3. Articulate the engagement process and ensure that you don’t distort it.

a) Depending on the procurement process undertaken before the project reaches your desk, varying levels and types of engagement might become possible, ranging from “consultation” (often least desirable) to true partnership. In your documentation, articulate the hierarchy of the decision-making – for instance, was there Indigenous leadership on the project control group?

b) Equally, the building type and/or governance structure of the project will impact on the engagement and design process: projects with Indigenous clients are different to projects with Indigenous stakeholders and again different to projects with Indigenous end users (and some projects are a mix of all of these, or none). Ensure that you appropriately articulate the process and structure.

c) Where appropriate, acknowledge how the project came to you – for example, were you invited by a community to undertake the project?

4. Check that there is reciprocity in both the project and the writing.

a) Ask yourself these questions: Who are you writing about the project for? Is it in good faith with the knowledge and time shared by the community? Does or can the writing provide any reciprocal benefit to the community?

b) Consider how reciprocity can be embedded. Ask the Indigenous representatives whether there could be any benefit to them from your writing about the project.

5. Share any relevant project-specific protocols to contextualize the project.

a) Some communities have specific protocols for working on their Country and with their representatives. Other projects might develop – in partnership with the Indigenous representatives – a series of shared protocols, values or principles that guide the design and decision-making process. If these protocols, values or principles were developed, articulate these where appropriate to contextualize the project.

b) With permission, articulate these shared protocols, values or principles to help clarify the aspirations for the project. Not every project can do everything, so articulating these aspirations can help explain to the reader, the profession and the wider community (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) what was prioritized in this project. These aspirations cannot be post-justified.

6. Develop your cultural understanding.

a) It is critical that all architects develop an adequate level of cultural competency in order to work effectively on projects that are used by Indigenous people (i.e. all public projects) or that are for Indigenous people. Initially, architects should undergo Cultural Awareness training – preferably designed and presented by local Traditional Owners – but deep competency is developed by working alongside Indigenous people and learning together.

b) Writing respectfully about your project demonstrates your Cultural Competency and provides a place to reflect on the efficacy of your processes as well as the overall delivery process and effectiveness of the project’s outcomes.

c) The term “2 Way Learning” is used to describe a way of working and learning together for mutual benefit. Where appropriate, articulate some of these benefits in your article.

7. Gain permission.

a) The authority structure in communities can be dynamic – people change roles, the structure of a community council may change, and views shift. Sensitivities within the community may also change over time. Note that the permissions granted for one article do not necessarily apply to another article.

b) While as the architect of the project you have a moral right to present and write about your work, ethically you must seek permission from the community to represent them in the writing with an appropriate authority.

c) The community should be provided with a copy of the text and images prior to publication, with adequate time for review (see 1c). Photographic representations (images of the community, Country and especially people) have Cultural significance and implications. In some communities, images of deceased people are highly sensitive; photographers must understand these sensitivities, gain permissions for publication and actively avoid using images that may become sensitive if, say, an Elder or community member passes away. Work with the Indigenous representatives to understand the most appropriate protocols for photography.

In addition to documenting a project, you may need to write about it in the context of an architectural awards submission. For many projects, awards processes are the media entry point – so the way the project is articulated is extremely important.

8. When writing for an architectural awards process, there are some extra points to consider.

a) The textual component of the submission is often quite short, which limits your ability to convey many of the points outlined in this guide. It may be useful to consider awards text as an introduction to a much longer article; therefore, it is important to touch on the key points that will be expanded upon at a later date (through the verbal component of the awards processes, articles that follow or the project’s description on your website).

b) If the project underwent an engagement process, this process needs to be explicit in the text. Mention the scope and type of engagement and describe how the engagement influenced the design outcome – it is important for an awards jury to understand whether the process was appropriate and celebrated by the community.

c) If the awards process allows, request that the Indigenous representatives provide a statement of support so that their voices are central to the presentation of the project and their permissions are explicit.

1. Depending on the area, an authorized community representative may be a Traditional Owner or someone appointed by the Traditional Owners.

Source

Practice

Published online: 6 Jul 2021

Words:

Sarah Lynn Rees,

Finn Pedersen

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2021