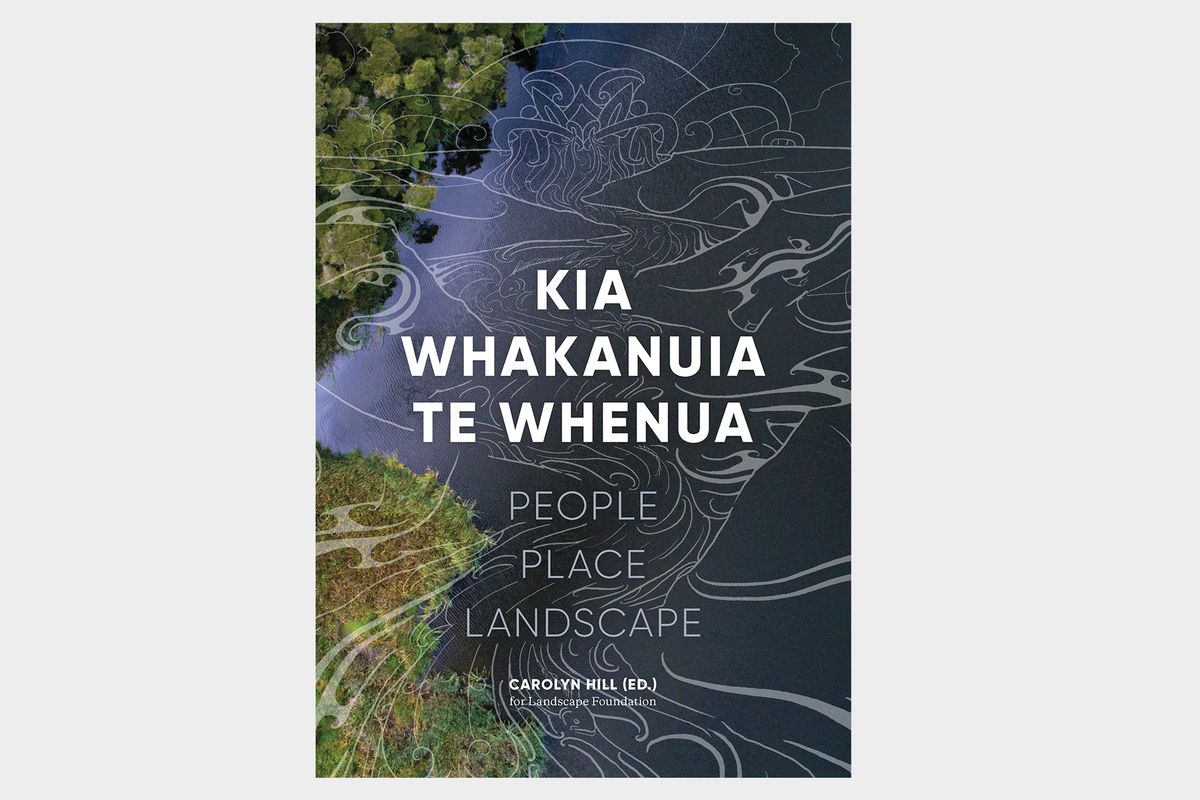

With Kia Whakanuia te Whenua: People, Place, Landscape, New Zealand’s Landscape Foundation has produced a deeply rigorous and challenging book with an overtly optimistic and generative tone, which deserves to be read widely by landscape architects. The book provides a rich documentation of the landscape and culture of Aotearoa through an examination of place and placemaking policy. It’s interwoven structure, with seven chapters and 34 essays, stories, photo essays and polemical pieces, provides a template for the expression of place through publication. This approach foregrounds Māori perspectives, voices and authorship and draws from beyond traditional landscape disciplines.

For the non-Indigenous landscape architect, the real power and challenge of this book lies in its demand upon the reader to understand and reflect upon their own place within each of the essays – and the collection as a whole. Avoiding the epistemological trap of relying on one’s own previous frame/s of reference to make sense of new ways of thinking about the world is difficult and, on my initial reading of the book, I found myself drawing equivalence between Māori concepts and familiar landscape architectural research principles. This need for conceptual equivalence extended to thinking about Australian Indigenous concepts of Country, with their emphasis on connection. The place here, however, is Aotearoa. There are principles at play from which we can learn but the place and the concepts are of that place; we must bring ourselves to that place rather than attempt to bring that place to ours. While there are areas of the book that tend to support this tendency towards equivalence, overall, the book mitigates against this, both demanding and facilitating the placing of oneself in it.

Haare Williams opens with a powerful evocation of colonization and the havoc wreaked on Māori culture as a result, but also brings us to confront the continuing power of language in abetting, embedding and solidifying colonial power structures to the detriment and desecration of Indigenous authority, ideas and practices. The relationship between thought and language forces the reader to take personal responsibility, with consequences for the future of the nation; for Williams, the need for truth-telling is critical for “democracy to prosper.”

Diane Menzies builds on this in her introduction, working across some familiar markers of “landscape” practice, foregrounding an approach that transcends the old binaries (nature/culture etc.) and inviting an engagement with time that grounds non-linear approaches and attitudes to the world. In doing so, she sets the book up to go beyond mere recognition and acceptance that “social justice and equity aligns with recognizing the range of … world views” to show how a deep understanding of these worldviews on their own terms is a precursor to action. In this way, social justice and equity are then embedded in the outcomes of such actions. Herein lies an existential challenge for the landscape architecture profession.

Early in the first chapter, “Wairua o te Whenua,” Alayna Renata writes of the “researcher’s trap of wondering what specifically to write about” in relation to “the spirit of landscape.” Abandoning the academic viewpoint (and quite arguably, the landscape perspective), she draws on her experience, as a Māori woman, of wairua (soul or essence)1 and whenua (land)2 to question the very possibility that academic research might have a role in developing an understanding of the concept of the spirit of landscape. Instead, she calls for recognition of this spirit as being a “lived and living knowledge … articulated through experience.” She captures an overarching point of the book: that “we can learn a lot from what people say they experience.”

In the concluding chapter, “Whakahāngai,”3 Gayle Souter-Brown draws on the profession’s genetic links to Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in calling for a “revisit of landscape’s contribution.” Advocating for evidence-based design from a health perspective, she suggests that “place-making has been supplanted by place-keeping” – itself perhaps a return to Olmstedian principles of “working up” the best of what already exists. Olmsted, while of his time, was animated by a visceral sense of social justice, challenging a set of national institutional assumptions through design. This remains the challenge for our profession – how to make a place in a national discourse of social and cultural justice. This book provides a methodological manifesto for this by opening the way for further landscape writing by Indigenous peoples telling their stories of experiencing the landscape and making place.

Kia Whakanuia te Whenua: People, Place, Landscape. Edited by Carolyn Hill for the Landscape Foundation. Mary Egan Publishing, 2021.

1. wairua – spirit, soul, essence. From the glossary. The book’s glossary is wonderful, as with any glossary however it should be treated with caution and seen as a starting point for understanding – much nuance and particularity can be lost otherwise.

2. whenua – land. From the glossary.

3. whakahāngai – to make the connection. From the glossary.

Source

Review

Published online: 7 Jun 2021

Words:

Jock Gilbert

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2021