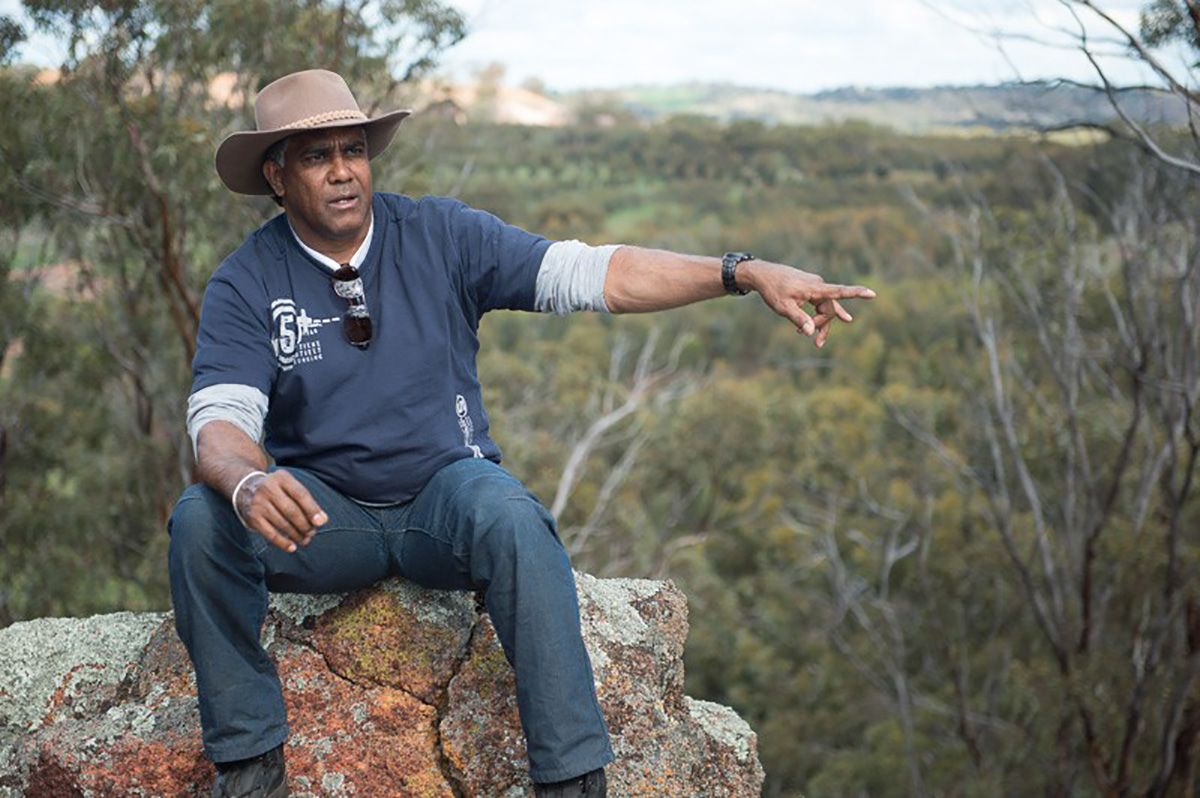

For a little over a decade, Oral McGuire has been working with Greening Australia and Yaraguia Enterprises, a group of Ballardong Nyungar people, to regenerate hundreds of hectares of land in south-west Western Australia using traditional knowledge systems and land management practices. As part of this work, the Marlak Niran Revegetation Project at Avondale Park near Beverley aims to create a Ballardong cultural landscape for future generations. Rosie Halsmith spoke with McGuire.

Rosie Halsmith: Could you tell us a bit about yourself?

Oral McGuire: My name’s Oral McGuire. I’m a Ballardong and Whadjuk Nyungar. I’m a Nyungar person who sees and understands our cultural responsibilities. Through my bloodline, I have strong connections with the lands of the Ballardong people [in the south-west of Western Australia], which extend out to the towns of Kellerberrin to Dandaragan, to Toodyay, and then all the way down to Brookton and Wagin. Then, to the area that’s directly due east of the [Perth] metropolitan area, over the Darling Scarp. The Avon River, Goguljar, is the central landmark of Ballardong country.

Could you speak about cultural land management practices on Nyungar country?

The issue of cultural land management is an interesting one, because Nyungar cultural practices have been disrupted. We’ve always been present on our country, on our Budjar, but our lands have been removed from our cultural authority. One of the things we’re working really hard on is re-establishing and reconnecting to cultural land management practice, [which is all about] caring for country and managing Budjar.

Could you explain the concept of Budjar?

Budjar is a big concept. The closest English translation would be universe or environment. Budjar is a very strong spiritual aspect of Nyungar identity. Caring for Budjar – well, that’s where our management practices become cultural law.

In the years since colonization, on Nyungar country, the establishment of broadacre agriculture has had a major impact on the health of the landscape. Could you speak to the significance of these alterations?

In the 1960s, in Ballardong country, farming was pretty good. We got regular and reliable rain. My dad drove tractors, and I sat on the tractor with him watching the beautiful soils being tilled and seeded. The land produced crops that were taller than my dad – he was six foot two. Today, I drive past those same paddocks and the crops are lucky to rise higher than the fence line, which is about three foot. Two hundred years ago, the land [in Ballardong country] was very well vegetated. Today, we have horrible, compressed, compacted soil. We’ve got massive problems with erosion. There’s a [significant] cost [associated with] healing that sort of country.

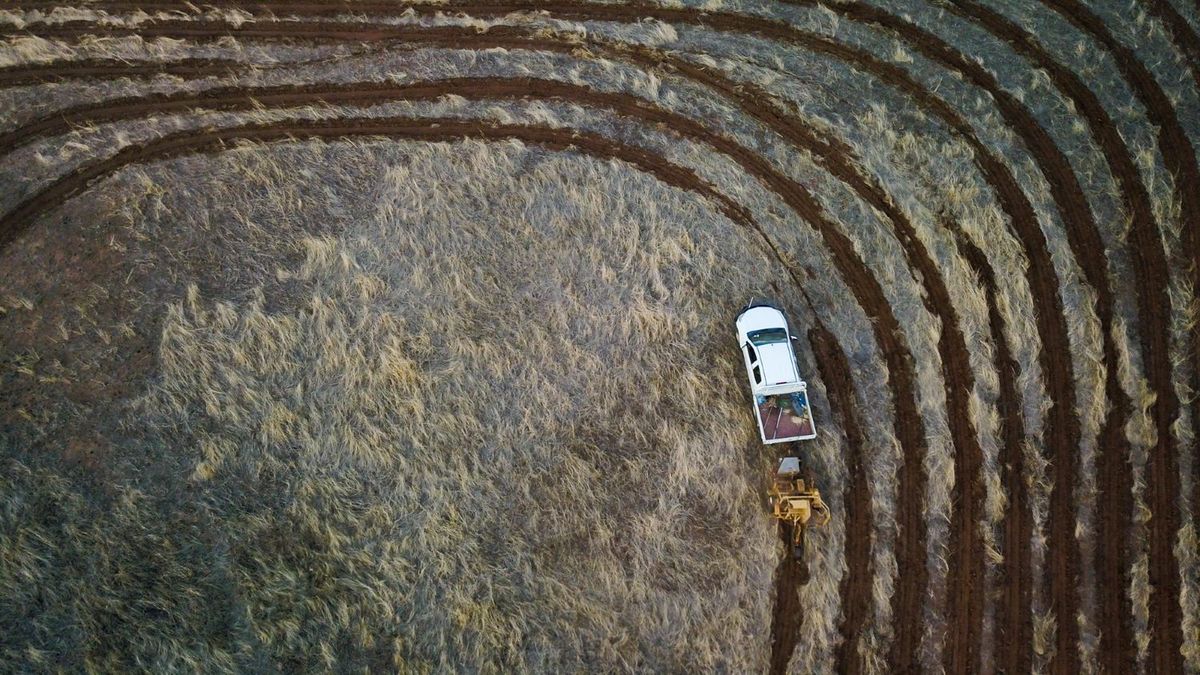

Direct seeding of the land at Avondale Park as part of the broader regeneration strategy.

Image: GA Photos

Could you tell us about the Marlak Niran Revegetation Project and the process of cultural land management that’s happening as part of that? What activities are being undertaken to mitigate some of the impacts on the landscape you’ve just described?

We [Yaraguia Enterprises] have been fortunate to acquire a piece of [Ballardong] land at Beverley [in the wheatbelt of Western Australia]. [Here, at Avondale Park,] we’ve developed a management plan to heal the property. For the past 12 years, we’ve been focused on managing the land in a culturally appropriate way. The most powerful stuff happens when Nyungar people return to their sacred lands, when they are given the authority to re-enliven country through cultural practice. Our first action was to remove livestock and machinery and [to reintroduce] natural elements, starting with the plants. We reintroduced [trees], native grasses and groundcovers – all species that are endemic to that landscape.

Our management practices are [driven by the idea that] we need to strengthen country with biodiversity. If we have the right species of plants, we’ll attract a variety of insects. The insects will attract the birds, and then we’ll also attract foragers – the little critters that scratch around, doing all the really good stuff with the soil. One of our sacred foragers is the echidna, the Nyingarn. We’ve got a really healthy Nyingarn population on our property now, that absolutely was not there before. We also have a really huge diversity of birds, and we’ve seen the soil improve – it’s softened. The most powerful thing is that, each year, we do this work of healing country and [we see continued growth, change and improvement].

What role does fire play within the broader cultural land management strategy of the Marlak Niran project? Could you speak to the significance of fire?

Kaarlngara [fire] is very sacred. I grew up connected to fire. A lot of our old fellows did the clearing of agricultural areas, right up into the mid-1970s. And as an eight-, nine-, ten-year-old, I remember going out with my oldies and watching them clear the land, burn it. I became a fire fighter in my adult years, before [moving towards] what is now termed “cultural burning.” Understanding and respecting fire, in our cultural way, is about knowing all of the elements of fire – its natural force and its natural beauty. The right fire, in the right country, by the right people, is a very powerful, spiritual thing.

At Avondale Park, I burn with a very specific intent to regenerate country. Over 12 years, we’ve planted half a million trees over 800 hectares. That country has now transformed [to a point where we can] go in and use the principles of cultural burning in a way that is productive. Our native grasses regenerate with fire, so [cultural burning] is a way of replenishing the health of country. It’s not about hot burns. Lighting a fire and burning the bejesus out of everything is not cultural burning – that’s just fire. That’s just a very quick and fast way of saying, “OK, burn everything so nothing can burn afterwards.”

Sunset falls over Avondale Park following the 2008 revegetation.

Image: GA Photos

Could you tell us some of the differences between cultural burning and prescribed burning practices?

Our old people burned regularly, to maintain balance. The Nyungar and Aboriginal people who hunted regularly used fire as a [method] of landscaping. That was a practice that happened over hundreds of years. They’d [burn the] landscape to get cover for their hunting practices. Managing and keeping balance in the natural system was just a part of human existence. Where fire was needed, it was applied. There was no burning season. Sometimes [our old people] burned at the end of summer, when things were dry. They knew that at the end of the burning, the rains would come, and that the replenished land would then be primed for the new season that would bring rich game for hunting and gathering. [Our old people] burned very regularly – whereas now burning is quite irregular. Some areas haven’t been burned for 10 or fifteen years. That’s dangerous, given our climate and the way it’s changing. The process of [prescribed burning] is commercially oriented – no one’s considering country.

Following this year’s bushfire crisis, the issue of fire management has had increasing visibility. Cultural management, and with it, fire management, has been undertaken by Traditional Owners for tens of thousands of years – with thousands of generations of knowledge gathered over these years. What are your thoughts on whether, and how, this knowledge could be shared, with appropriate cultural leadership?

What we need to do is to collaborate. To bring spiritual wellbeing back into natural systems, we must have [the involvement of] Nyungar [and Aboriginal] people. There needs to be a renewed focus on what is it that Nyungar and Aboriginal people bring to this conversation. When we become involved, and when we become empowered through that involvement, things happen. Land is being healed. We have got to be respected, to hold to our cultural ways and our cultural law. We must be engaged. Not just because we’re Nyungar, but absolutely because we’re Nyungar. Nyungar know who the right people are to light the right fire. And what our country needs is the right fire.

Source

Practice

Published online: 22 Oct 2020

Words:

Rosie Halsmith

Images:

GA Photos

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2020