When Captain Cook visited, in the 1700s, what we now know as Sydney Harbour, he described abundant oyster reefs, tidal fringes lined with saltmarsh and mangroves, and sandy beaches. Today, more than two and a half centuries later, seawalls dominate the foreshore of the harbour, with oyster reefs long lost and forgotten. Compared to the habitats they have replaced, these seawalls typically support less biodiversity.

Since 2015, the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS) has partnered with Melbourne-based designer Alex Goad of Reef Design Lab (RDL) to bring seawalls back to life. The relatively flat and featureless surface of seawalls provides little space for marine plants and animals to live, and those that do, struggle to find protection from predators, wave action and the midday sun. The poor habitat quality of seawalls is particularly apparent when compared with rocky shores – seawalls’ closest natural analogue. Where the rockpools and crevices of rocky shores teem with seaweeds, anemones and crabs, often only the hardiest of species can survive on seawalls. In Sydney Harbour, the species currently living on seawalls include the rose barnacle and purple four-plated barnacle, the cap-shaped false limpet and snails including the mulberry whelk and banded periwinkle.

A SIMS scientist monitors marine life on the habitat panels which have been attached to existing seawalls.

Image: Leah Wood

Sydney Harbour is not alone in being a seawall-dominated seascape. The sprawl of human settlements from the land to the sea is a global phenomenon. For millennia, seawalls have been constructed to stabilize reclaimed land, support port infrastructure, and to hold back the sea and floodwaters. As sea-levels rise, a new wave of seawall construction has been taking place.

While it will be difficult to turn back the clock on seawalls, the SIMS–RDL team is leading a growing branch of ecology – eco-engineering – that seeks to mitigate some of the impacts of marine built structures by incorporating ecological principles into their design. Over the past several decades, evidence of the benefits to biodiversity of incorporating holes, pits and cracks into seawalls has emerged from small-scale experiments. However, to enhance biodiversity at the scales that matter to fishery productivity, maintenance of clean water and nutrient cycling, larger-scale efforts are required.

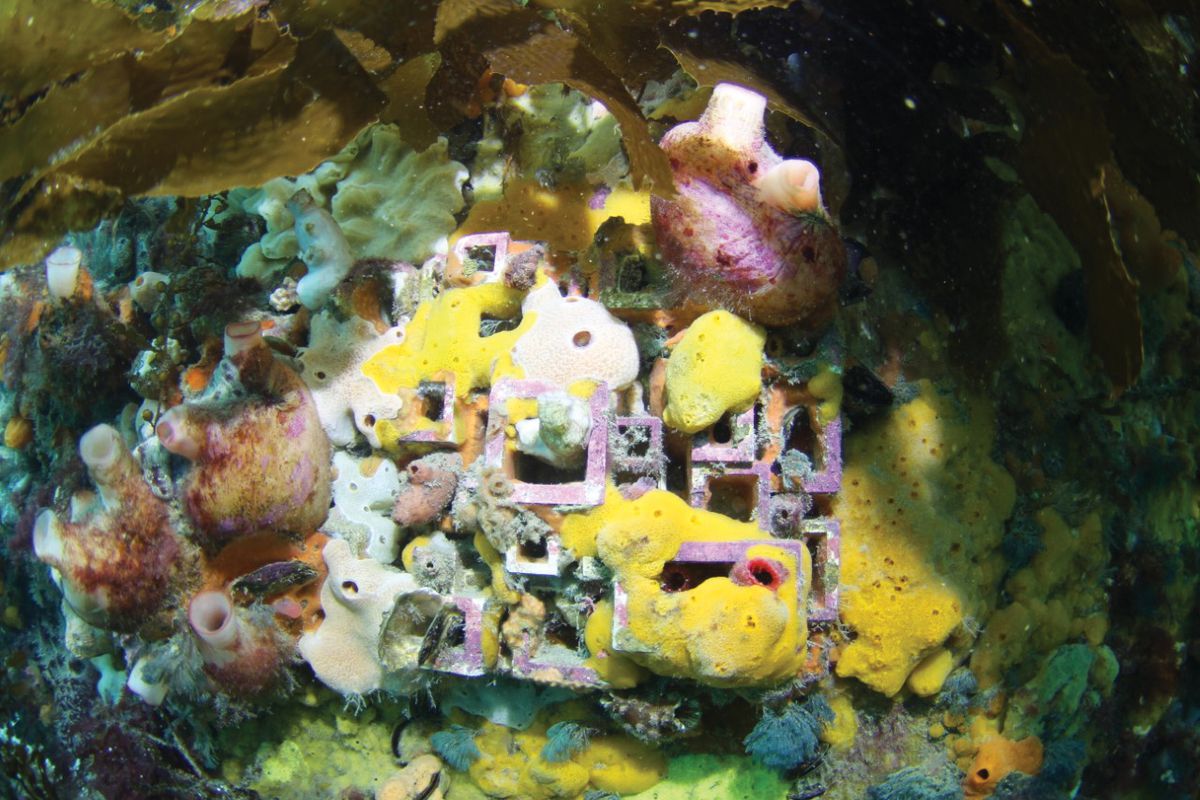

Under the banner of the Living Seawalls project, the SIMS–RDL team has developed modular habitat panels that can be attached to existing seawalls to increase habitat area and add missing microhabitats, such as rockpools and crevices. The panels come in a variety of designs, closely modelled on the textures and topographies of natural rocky shores, and can be customized in their configuration. A common element of the designs is that they each appreciably increase the habitat area of seawalls and offer moist or protected microhabitats that would otherwise be absent.

Within days, habitat panels can serve as “hotels” for fish.

Image: Alex Goad

The first installation of 50 Living Seawalls panels, covering a 12-metre length of seawall, was completed under the Sydney Harbour Bridge, at Milsons Point, in October 2018. More than a year on, the results are promising. Over 95 species have colonized Living Seawalls panels there and at nearby Sawmillers Reserve on McMahons Point, where there are 108 panels covering two 12-metre lengths of seawall. Of these species, only four are common to all six of the panel designs trialled to date, demonstrating the importance of providing a diversity of habitat features for marine life at a single site. Among the species found on the panels are rockpool dwellers such as anemones (including the orange and white stripe anemone ), grapsid crabs and seaweeds. Already, the ecology of the Living Seawalls panels is converging on that of natural rocky shores.

The team is now looking further beyond biodiversity to consider how Living Seawalls can provide fish habitat, and improve filtration of water and carbon sequestration. The hollows created by the surface of the Living Seawalls panels provide a resting place and home for small fish, including the oyster blenny and the Clarke’s triplefin. Larger fish, such as bream and luderick, feed on oysters and mussels growing on the panel surface. Those oysters and mussels that escape predation by hiding in the crevices and depressions of the panels can serve as important filters, helping to maintain clean water quality. Seaweeds colonizing panel rockpools, like land plants, sequester and store carbon.

The panels reintroduce absent or rare habitat features to the seawalls, such as rockpools.

Image: Leah Wood

Eighteen months on from the initial Sydney Harbour installation, 275 of the 55-centimetre-in-diameter Living Seawalls panels have been installed across six sites. Interest in the panels has been received from organizations including the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Climate Change in Gibraltar and the Estuary Care Foundation in Adelaide. The team is now turning its attention to how such approaches may be applied to other built structures in the marine environment (such as pilings) and how new structures may be designed to foster particular habitats prior to their construction.

As human populations in the coastal zone continue to grow, the SIMS–RDL team’s vision is of cities, where the adaptation of human settlements to environmental change need not be at odds with the needs of other inhabitants of our ecosystems. The opportunity exists to integrate ecosystem processes and biodiversity into landscape-scale interventions for the benefit of both humans and our non-human neighbours.