Roma Street Parkland is a sixteen hectare park located in the centre of Brisbane and listed as an iconic touristic destination. Its “Seasonal Plants” brochure promotes this space as “one of the world’s largest subtropical gardens in a city centre.” This statement immediately opens up an expectation to visitors – they are here to visit a garden, not a park. It also discloses and celebrates the programmatic agenda set by the Queensland government brief, which required that by the end of the twentieth century, Roma Street Parkland provide “a high-level visitor attraction with emphasis on horticulture and the environment.”1 The parkland opened to the public in 2001 and almost two decades later one could argue that the success of its sociocultural reception is expressed in the sheer number of its visitors, activities and volunteers. In 2018, 85 volunteers contributed to the presentation and maintenance of the space and two million people experienced its grounds through 220 public events, 185 guided walks, or simply as part of their daily routine.

The parkland embodies the materiality and vibrancy of time, concealing the many struggles of the land upon which it was built. Like other spaces of its type, it is the outcome of particular political, economic and sociocultural conditions. In this particular case, one cannot ignore the influence of the success of a specific event: Expo 88. This $625 million fair, which reclaimed an expansive post-industrial area on the city’s south bank, inserted a new paradigm into the Brisbane collective cultural and political sphere relating to urbanity and public space. This, in combination with sociocultural enthusiasm, urban aspiration, economic opportunity and political strategy, prompted the reclamation of an additional area close to the city centre for the creation of the Roma Street Parkland. The political scene supported and debated the environmental and social benefits of a park in the city centre and the real estate industry speculated the renewal and development of the city’s urban west. Roma Street Parkland was an indirect means for achieving this goal.

The site sits on the land of the Turrbal nation and its history is contentious and complex in both cultural and ecological terms. During the early decades of the nineteenth century, the deforestation process started while the area’s Aboriginal people still gathered food and conducted ceremonies on the site’s former wetlands. This process – and the massive earth operations that were undertaken to install the area’s railway system, stations and yards in the last quarter of the century – irreversibly transformed the site’s social and natural ecologies.2 These processes coincided in 1875 with a social and political momentum that declared that part of the land had to be reserved for parks and recreation – a framework that set the grounds for the construction of Roma Street Parkland some 120 years later. In less than a century, the marks of the colonial cultural grafting process became indelible, inscribing a spatial order that for almost a century would see the site relegated to a peripheral condition. The political powers commissioned an inscription of their ways of seeing and imagining landscape and city. The park therefore became agency to reconcile urban, social and ecologic disjunctions.

Since 1975, landscape architecture has been indebted to Richard Haag’s Gas Works Park, George Hargreaves’ Candlestick Point Cultural Park and Peter Latz’s Landschaftspark Duisburg-Nord. These projects legitimized new operative grounds and catalyzed a paradigm shift in landscape architectural practice. Derelict lands challenged the profession to experiment anew: “bad” sites had ceased to exist. Paradoxically, twenty-five years later, display and flower gardens such as the Butchart Gardens in Canada and Keukenhof in the Netherlands were the precedents suggested in Brisbane to a multidisciplinary consortium that included DEM Design, Civitas (Vancouver), Gillespies Australia and Landplan Studio. The consortium planned a broad strategy to transform a derelict and disconnected terrain into a sort of oasis of tropical beauty in the centre of the city, reconnecting the site to the continuum naturale and urban fabric by intertwining fragments of local heritage and public space, post-industrial land and apparatuses and disconnected topographic levels. It designed a vision, a whole new referent of public space for Brisbane. An exhaustive analysis of the biophysics of the site and a long stakeholders and community consultation process preceded the proposal’s development. The extent of the project was significantly larger than the current state of the parkland. In the end, approximately 30 percent of the original proposal was not built and a token of the project was cancelled: the affiliation with the Smithsonian Institution to research and promote biodiversity and tropicality in urban conditions. Many of the parkland’s spatial, cultural and environmental ambitions were therefore undermined and the project was not completed.

Roma Street Parkland is organized as a series of themed spaces and incorporates a complex and computerized irrigation system hidden and integrated into the form of a lake and a lawn. The design reflects the repertoire of Victorian-style gardens and parks, which, in conjunction with the integration of a rich and varied subtropical flora collection, creates an assorted ornamental assemblage. It is in these terms that Roma Street Parkland represents a missed opportunity. Rather than embracing the chance to expand landscape architectural critique and practice by exploring postcolonial readings of the site, the park’s syntax and style remains conservative. This claim does not envisage returning the site to its distant beginning, fetishizing or naturalizing its history, but rather, contemplates opportunity and a landscape architecture ethos.

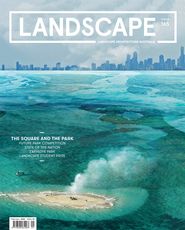

Bridges, wetlands, lawns and collections of subtropical flora at the parklands invite visitors to explore.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Today, a playful and identifiable atmosphere gives the visitor a sensation of shared placeness. Miniaturized forest environments, cascades, artworks, wetlands, lawns, bridges, floral gardens and meandering paths animate the space and draw the visitor into exploration. Roma Street Parkland constitutes a dissonant heritage encapsulating different meanings about its reality. In two decades, the social reception, appropriation and assimilation of this space as a cultural and environmental asset has situated it among Brisbane’s most popular attractions.

Roma Street Parkland is still becoming a palimpsest to open up future collective consciousness. Its relevance resides less in what it represents or presents today than in what its grounds and actuality conceal. The parkland reinforces the need to continue examining prevalent concepts of nature and landscape, environmental determinism and ideals of social justice in the projects and through the practice of landscape architecture.

1. Laurie Smith, “Roma Street parkland: past, present and future heritage,” 2003, Queensland Review, (St Liucia, Qld) vol 10 no (2), p.149–158.

2. ibid.

Source

Review

Published online: 6 Jul 2020

Words:

Claudia Taborda

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, February 2020