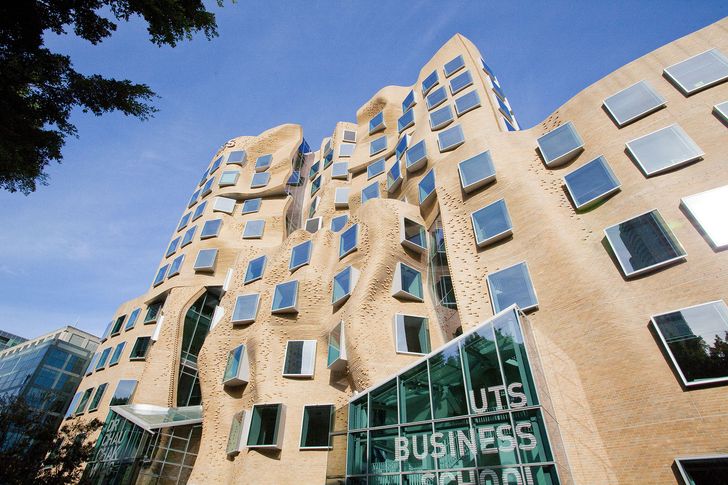

This May the Gehry-designed UTS Chau Chak Wing Building hosted over 200 delegates on the occasion of the 2017 Landscape Australia Conference. International and regional guests spoke on a range of themes from the perspective of their own landscape-orientated practices. These practices were chosen to facilitate the exploration of the dynamic role of landscape in the design, planning and management of gardens, cities and regions; the breadth of topics a nod to Landscape Australia’s broad readership. Across three thematic sessions, conversations traversed topics of aesthetics, indigeneity and urban resilience.

Few in attendance were likely expecting such varied guests and topics to deliver a unified conversation. On the surface, at least, this held true; a series of discrete discussions on a range of practices located across the United States of America, Netherlands, Morocco and Aotearoa (New Zealand) seemed to stay true to the event’s thematic silos. However, on closer inspection, a subtext pervaded the day’s events that spoke to the realities of practising in a world where scientific fact, moral standards and due process seemingly carry little weight. For this reason, Sydney’s very own Gehry could be seen as a fitting venue; both the building’s logic and material expression serve as an analogue for the current state of the body politic, one that far surpasses the building’s Trumpesque orange hues. In the words of architecture critic Philip Drew, the building revels in the “superfluous and overstates the unnecessary,” existing as an “unreality” that is permanently on the brink of collapsing.

The Frank Gehry-designed Dr Chau Chak Wing Building at University of Technology Sydney was the venue for the 2017 Landscape Australia Conference.

Image: Neil Fenelon

Experiences of the unreal often provoke a sense of disassociation, whereby someone perceives a lack of spontaneity and emotional colour and depth; feelings that are also associated with the sensation of placelessness. The absence of something and/or someone specific, as implied by the concept of placelessness, characterised many of the projects profiled at the conference – landscapes defined by suppression, degradation and erasure. In response, designers pursued practices led by the prefix “re,” as in once more, afresh or anew. Grounded in knowledge of place and a belief in landscape’s intrinsic value, emphasis was placed on the desire, if not the need, to reinterpret, restore, reinstate, reconcile and represent those aspects of a site’s reality that are increasingly inconvenient in our counter-factual world.

Thomas L. Woltz, principal of Nelson Byrd Woltz, charismatically opened the conference, presenting a body of work that included a memorial to September 11’s downed Flight 93, a plan to revitalize Houston’s Memorial Park, a garden commissioned by the Aga Khan for the Alberta Botanic Garden, and a conservation master plan for the privately owned and operated Orongo Station on the east coast of Aotearoa. Thomas’s presentation emphasized an approach to design that sought to honour and reveal local history and natural context, emphasizing narratives of loss, repression and divestment. This was framed in terms of a renewed desire for authenticity across the USA. In the face of this and related challenges, many of Nelson Byrd Woltz’s larger public works employed large-scale structural plantings in an effort to realize change in space and time at both the level of a site’s urban relations and a patron’s subjective experience. Eschewing conventional political and municipal time scales, these projects are designed for the longue durée. In the case of Houston’s Memorial Park, formerly the site of Camp Logan, a WWI training camp, large-scale tree plantings will be felled upon reaching maturity in an act designed to remember and honour the soldiers who lost their lives overseas. One wonders whether Houston will be prepared for the shock of the real when it comes time to fell the trees.

Forest Edge, Hokkaido, Japan, 2004 – from the Japan series. In NBW’s design for Houston Memorial Park large-scale pine plantings will be felled upon reaching maturity in an act designed to remember and honour the soldiers who lost their lives overseas.

Image: Michael Kenna

Bringing discussion closer to home, the second session of the day welcomed historian Bill Gammage, author of The Greatest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, and landscape architect Ralph Johns of the practice Isthmus, based in Aotearoa. Ralph framed the standing of Aotearoa’s Indigenous people through a discussion of cultural resurgence, drawing parallels between his adopted homeland and his place of birth, Cymru (Wales). In this context, Ralph illustrated a role for landscape architecture as a means of facilitating the assertion of Māori identity and cultural practices within the country’s ‘bi-cultural’ landscape. Onehunga Foreshore provided a potent example of such an approach. Isthmus has worked with local iwi (Māori tribes) and Pākehā (non-Indigenous) to reinstate Onehunga’s beachfront, located on Auckland’s Manukau Harbour. Infrastructural growth during the second half of the twentieth century led to the reclamation of a large extent of the foreshore and placed severe limitations on access. Referencing the site’s historical shoreline and the regions habitat, the project aimed to reintroduce a performing littoral zone that “fitted” with the place, both in respect to culture and biota. This fit, for Isthmus and the project’s patrons, was most effectively achieved through the creation of large-scale earthworks that appeared not to be constructed but as if the resulting landform had always been there.

As a reminder of how far Australia has yet to travel, as well a register of the particularities that continue to define the predicament faced by Australia’s First Nations people, discussion of Australian indigeaneity looked to the past. Drawing on his acclaimed book, Gammage provided delegates with an exquisitely illustrated thesis, arguing for the long-standing existence of sophisticated Indigenous landscape design and management practices. By way of historic surveys, diary entries and landscape paintings authored by early European settlers, Gammage accounted for a “constructed” landscape that European’s equated with a “gentleman’s park.” No one at the time thought to ask how such a park was made. Blinded by their prejudices, European’s were unable, and likely unwilling, to conceive that the landscape they had found was not natural but in fact the product of intentions, achieved through an extensive use of fire. As Gammage stated, and modern experience repeatedly illustrates, it is not a question of fire or no fire; Australia is made to burn. This potent statement served as a call to the conference’s audience to reconsider the essential role of fire in the continual remaking of Australia.

Isthmus has worked with local iwi (Māori tribes) and Pākehā (non-Indigenous) to reinstate Onehunga’s beachfront, located on Auckland’s Manukau Harbour.

Image: Courtesy Isthmus

Discussion of the constructive destruction wrought by fire speaks to Thomas Woltz’s interest in the “destructive efficiency” of nature, something all too familiar to the day’s final speaker. Sylvia Brands, founding partner of Dutch practice Karres and Brands, operates within a constructed landscape that faces growing threats from climate change. Inundation from both the North Sea and Europe’s largest riverine system means that the Netherland’s low-lying land base is encircled by threats, placing the country’s infrastructure, and its economy, at increasing risk of collapse. In response, the mechanistic structures cleaving the country’s terrestrial and hydrological systems apart are being reimagined as resilient interfaces that operate spatially at the physical and temporal scales of the landscape. This approach counters the same types of dissociative feelings provoked by the aforementioned tendency towards unreality. In the Dutch context, historic attempts to suppress the landscape’s ability to act spontaneously have invoked a complacent attitude toward impending threats. Recognising that the factually supported realities of our time present an existential threat, the Dutch government has invested billions of Euros into a project that seeks to reconcile the country’s complex relationship with water.

The examples singled out for discussion in this review account for landscape practices that are meaningfully addressing the distrust and insincerity that characterizes our time. However, the means by which these practices have traditionally realised their aims are weakening. Factual evidence, moral standards and due process can’t be relied on to safeguard landscape’s intrinsic value. Landscape practices will need to find a louder (or possibly alternative) voice in order to realize their aims. Like landscapes, unrealities and false-truths are the product of inventive narratives. When the fight demands more than figures, our stories – metaphor and meaning – need to be the subject of a renewed emphasis, and it’s likely the stories invested in our homelands, expressive of a place’s inconvenient realities, will prove the most potent.