Landscape architects visiting MUMA’s exhibition Tree Story will need little proselytizing to be on board with the central question posed by the curators: “What can we learn from trees and the importance of Country?” In our shaping of places, trees are an essential tool, lending structure, identity, beauty and shade, and providing seasonal change and habitat. We understand that trees are more than living organisms; they are containers of memory and signifiers of culture.

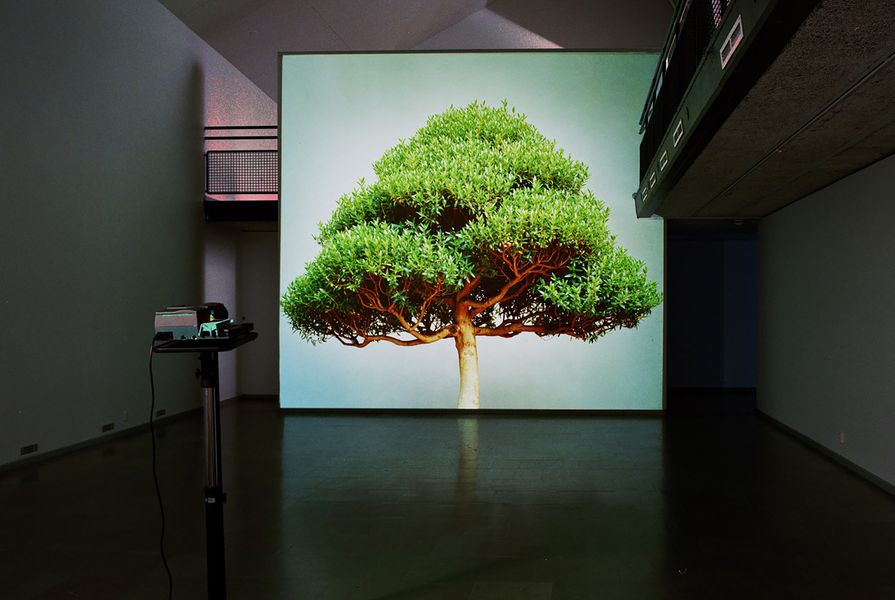

The stated aim of the exhibition is to provide a “forest of ideas,” but as a highly curated and controlled display, I would venture that it is instead an ar(t)boretum. The works in the exhibition cover a wide range of conceptual, spiritual and physical relationships between humans and trees and, in one of the works, between trees themselves.

There is more than one story in Tree Story. Miniature trees are made life-size and large trees are burnt down into ash to glaze small ceramic logs. There are trees constructed in the mind’s eye and fantastical chimeras of spliced tree genera. Branches reach up to the ceiling and trunks lie flat on the floor. The woodland planting of ironbarks in the Ian Potter Sculpture Court, framed by the gallery windows, is drawn in as an incidental participant.

Reena Saini Kallat, ‘Siamese Trees’ (Man-yan), 2018–19.

Image: courtesy the artist and Chemould Prescott Road

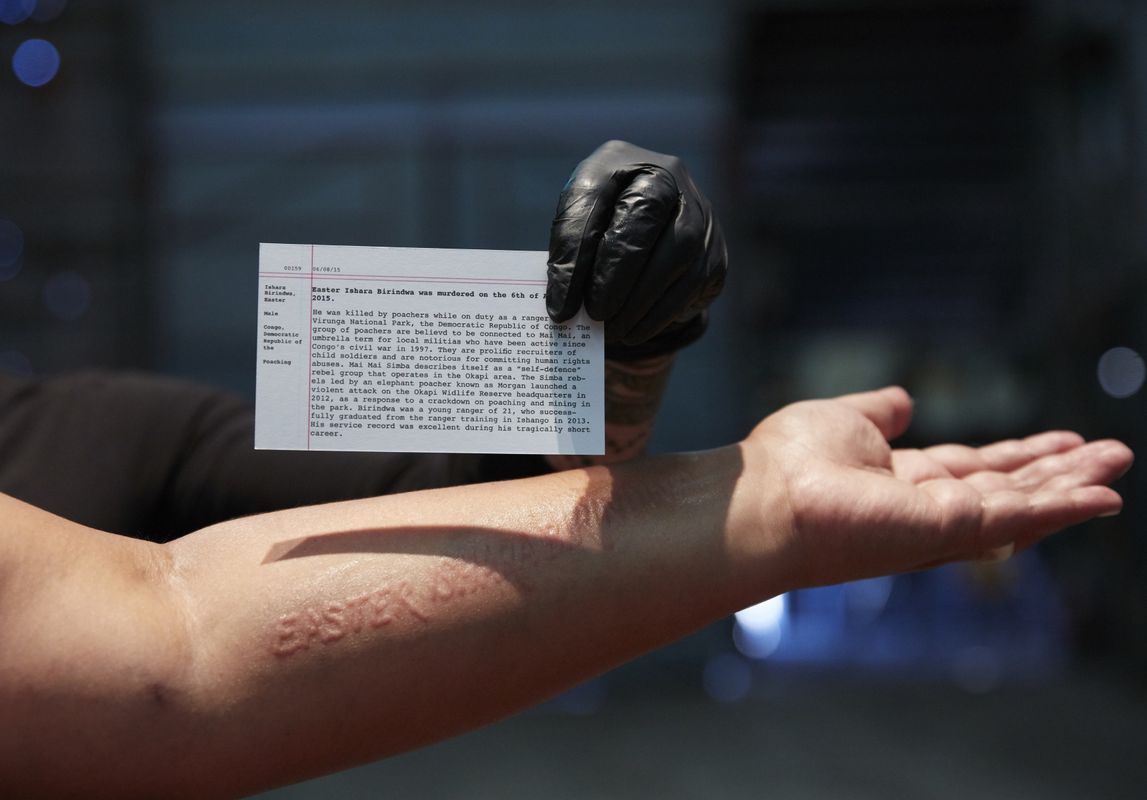

Trees are politicized. They stand silent witness to horrific natural and man-made events and provide a tangible connection to the past, as in Swiss-born cinematographer Uriel Orlow’s negative photographs of trees in South Africa, each connected with a dark colonial legacy.

In recent years there has been much scientific research on the topic of plant sentience and communication, and Russian artist Olga Kisseleva’s intriguing installation uses sensors and electronic devices to record interspecies conversations initiated between trees in Paris, France; Tokamachi, Japan; and the Wollemi National Park in New South Wales. There are two screens – one depicting the distant trees and the other their conversations, while a real Wollemi pine sits, a little sadly, in a pot. I stand watching the screening of the emitted signals – the slowly pulsing red dots blur and fade, to be replaced by blue rings. It’s strangely mesmerizing, like watching an iPhone booting up. What are they talking about? How should we understand this non-visual, non-human consciousness?

The exhibition features several photographic works created during the emerging environmental activism of the sixties and seventies. These document performances and participatory actions with, on, or about trees and include Joseph Beuys’ 1972 work assembling a mob to brandish sticks at impending development and Stelarc’s 1982 efforts to find a tree with just the right bough structure for his Prepared Tree Suspension: Event for Obsolete Body No. 6. Melbourne-based artist Jill Orr’s suspension in Bleeding Trees (1979) is quite different – you can almost hear the sigh breathed through her open mouth as she sinks into the embrace of the bough that cradles her.

Jill Orr, ‘Bleeding Trees,’ 1979

Image: Elizabeth Campbell for Jill Orr

A more immersive form of interaction is provided by Brazilian-based Daniel Steegmann Mangrané’s virtual reality environment, Phantom. Strap on a headset and be transported into the forest as a point-cloud survey. I found this experience to be initially wonderous, but this feeling soon changed to sadness when I was reminded of what is at stake. Is this all that will be left, if our response to the climate crisis fails – digital dioramas of lost environments?

Tree Story is, for the most part, serious business. A rare moment of levity is afforded by Franco-Moroccan Yto Barrada’s video work A Guide to Trees for Governors and Gardeners, which follows a procession of official government vehicles through an animated city model. Avenues of palm trees amusingly pop out of the pavement to provide temporary beautification when, and only when, the motorcade passes, retracting shortly after their propaganda hatchet-job is done.

Peter Mungkuri OAM with his work ‘Punu’ (Trees), 2020.

Image: courtesy Iwantja Arts

At the core of the exhibition is a focus on Indigenous knowledge, care and love for trees, and the power of imagination in constituting what trees mean for Country. This narrative is reinforced at the intersection of works by Wiradjuri artists Nicole Foreshew and Brook Garru Andrew, which present a potent dialogue around authenticity, belonging and loss. Andrews’ Powerful Object: Dendroglyph is a 3D-printed facsimile of a ceremonial tree carving kept in the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford University, secured to a steel platform trolley with a bright blue tie-down strap ready for delivery. The “plastic-ness” of the translucent yellowish tree object is heightened by the earthy and specific material connection to place of Foreshew’s Mabuwurda (noise of the cracking of crossing branches caused by the wind), a wall-length installation of tactile branches coated in fine, powdery white clay that crackles and flakes across the timber’s weathered surface.

Trees were here before us, but will they be here after us? The message of the exhibition is clear. Only by careful and respectful listening, being wise in the way of caring, and through collective action can we endeavour to write Tree Story a happy ending.

Tree Story is on show at Monash University Museum of Art until 10 April 2021.