The title of the 2021 Festival of Landscape of Architecture, “Spectacle and Collapse: Changing Landscapes,” seemed somewhat ironic for a conference in relatively “normal” Perth to those of us watching on from cities still in lockdown. The relevance of the title – derived from Guy Debord’s 1967 Marxist critique The Society of the Spectacle – remained understandably ambiguous during the conference, often referred to but never resolved, which could also be said of the issues that it sought to address, including the relationship of nature and landscape to ubiquitous media and climate change. Located in magnificent Kaarta Koomba (Kings Park), the conference had a peculiarly Westralian vibe and was characterized by a particularly broad range of disciplines and topics addressing the overall theme.

Christina Nicholson, a member of the 2021 Festival of Landscape Architecture creative directorate. The creative directorate comprised Maria Ignatieva (UWA), Christina Nicholson (UWA), Damien Pericles (Realmstudios), Hans Oerlemans (Wonder city and landscape) and Kat Stewart (student representative).

Image: Ilkka K Photography

The view of the Perth CBD from Kaarta Koomba (Kings Park).

Image: Ilkka K Photography

The “international keynote” is a normal feature of a design conference in Australia, where the antipodean locals learn from those in the “old world.” One of the great successes of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects’ adoption of the “festival” model of curation – where city-based teams pitch and develop their own themes and select their own speakers – has been a focus on the local. However, part of the “spectacle” is the internet and “the socials,” which have catapulted Australian landscape design to the world stage, revealing the undeniable innovation of Australian landscape architecture and making the global, well, not so special. This was certainly the case with Darius Reznek of Karres en Brands’s presentation this year. While the Dutch practice’s design for Federation Square – and its role in helping engage Australian landscape architecture with European design culture – was vitally important to the development of the profession here, their work as presented did not seem radically better or different to that which has come out of Australia in the past 10 years; I guess we (Australian landscape architecture) have “made it.”

Kaarta Koomba is a unique park: part botanical reservoir, indigenous landscape, topographical feature and central park. As a venue choice, it was a sign that the botanical was at the centre of the conference. And with horticultural researcher James Hitchmough taking centre stage as the true international keynote, it seemed plants had returned (hallelujah!) to the centre of landscape discourse. Much of the interest in naturalistic planting in the past 10 to 15 years has focused on initial species selection and qualities. Given this context, Hitchmough’s admonition to think about projects post-implementation was welcome, however his emphasis on the creation of soil conditions to ensure that landscapes remain as close as possible to their original intentions failed to recognize the transformative potential of maintenance as a creative process.1

Left to right: Kingsley Dixon, Nathan Greenhill, Digby Downs, Maria Ignatieva.

Image: Ilkka K Photography

Wildflower season in Western Australia.

Image: denisbin, CC licence via Flickr

Western Australia seems – and has sought to be – a separate country to the rest of Australia. Cape Town, for instance, seems more botanically similar to Perth than Sydney does, sharing an edge of Gondwanaland as it does. Curtin University botanist Kingsley Dixon, in his presentation, discussed an early European depiction of the state’s landscape – the incredible, 2.5 metre-long Panoramic View of King George’s Sound, Part of the Colony of Swan River by Robert Havell, published in 1834. He noted the diverse flora in the picture, as well as the presence of smoke indicating the presence of Indigenous fire practices. Kingsley’s presentation, as well as that of novel plant breeder Digby Growns, established the first instance of “spectacle” in the conference program as the “spectacular” flora of West Australian plants. Nathan Greenhill, head of design for WA’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions, noted the paradox of botanical tourism – tourists who come to watch natural spectacles such as the “wildflower season” are good for the economy, but their presence can threaten the same species that brought visitors there. Since a spectacle requires a viewer, spectacle has an inherent relationship to mediation, particularly in the age of image-based social media. “Green” it seems has become this kind of spectacle, evident in advertising creative director Karen Ferry’s discussion of contemporary “trends” in gardens and landscapes. The content of Ferry’s talk gave rise to the odd feeling of having the discipline mirrored back on itself. Her presentation was the most “Debordian” in the conference, typifying the rising kind of consumption noted in The Society of the Spectacle.

Detail of Panoramic View of King George’s Sound, Part of the Colony of Swan River (1834) by Robert Havel.

Image: Wikicommons

Panoramic View of King George’s Sound, Part of the Colony of Swan River (1834) by Robert Havell.

Image: Wikicommons

When “Collapse” came to the conference, it came in a big, disturbing, squirm-in-your-seat – way, as views that pushed at the norm or moved across poles to the “other side” of politics were aired. In one perplexing and memorable session, Canadian “systems analyst” Nicole Foss, discussing climate change, made the end of a growth-based capitalism – or “peak everything” – seem like a foregone conclusion, with her suggestions for localization of governance and technologies resembling instructions for “preppers” anticipating the apocalypse. The tangible conspiratorial quality of Foss’s relentless narrative had me Googling to see if she was an anti-vaxxer, as much a reflection of how particular ways of talking have become synonymous with certain ideologies as it was with what she said. In retrospect, her description of what she calls “solution space” was logical and sensible in its suggestion that approaches should be “small-scale, local and simple” rather than top down, high-tech or capital intensive. Julia Watson’s recent treatise on indigenous design practices, LO–TEK, was brought to mind.

With a strong and integrated Indigenous dimension to the conference, it’s not surprising that the rawest and realest accounts of collapse came – with some anger – from First Nations speakers. Noongar man Oral McGuire, in particular, noted that “Spectacle and Collapse” was a lived reality that could describe the “rollercoaster ride” experienced by Indigenous people in Australia, and in Western Australia in particular. In discussing the recent wave of attention given to Indigenous fire practices – and in what could also be seen as a critique applicable to Watson’s book – he noted that Indigenous environmental practices are more than simply “technology by another name,” cautioning that “sacred means secret,” and that such knowledge and practices have very specific names and codes among Indigenous communities. McGuire’s presentation reminded me of a conversation with a colleague in the landscape architecture profession who noted that “Whitefellas have impacted indigenous landscapes and people, and now we seem to think that Blackfellas will fix it all up for us.” Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones also spoke about how “country is trauma now,” with the character of it now indivisible from the impacts of colonisation, including deforestation and degradation. Jones brings a highly tuned landscape sensibility for ephemeral process to his work to give an elegant voice to this trauma, reframing symbols of colonisation through art. Inflecting traditional stories with some wonderfully post-modern Australian analogies, Jones told how a Bathurst uncle used the duel between car manufacturers Ford and Holden to retell a Dreaming story about Wahluu (Mt Panorama), illustrating how new narratives were arising from traumatized country. The hybridity of Jones’s approach is an example of the dialogue between Indigenous tradition and contemporary creative practice which is becoming increasingly and excitingly evident in Australia.

Oral McGuire discussed Indigenous environmental practices.

Image: Ilkka K Photography

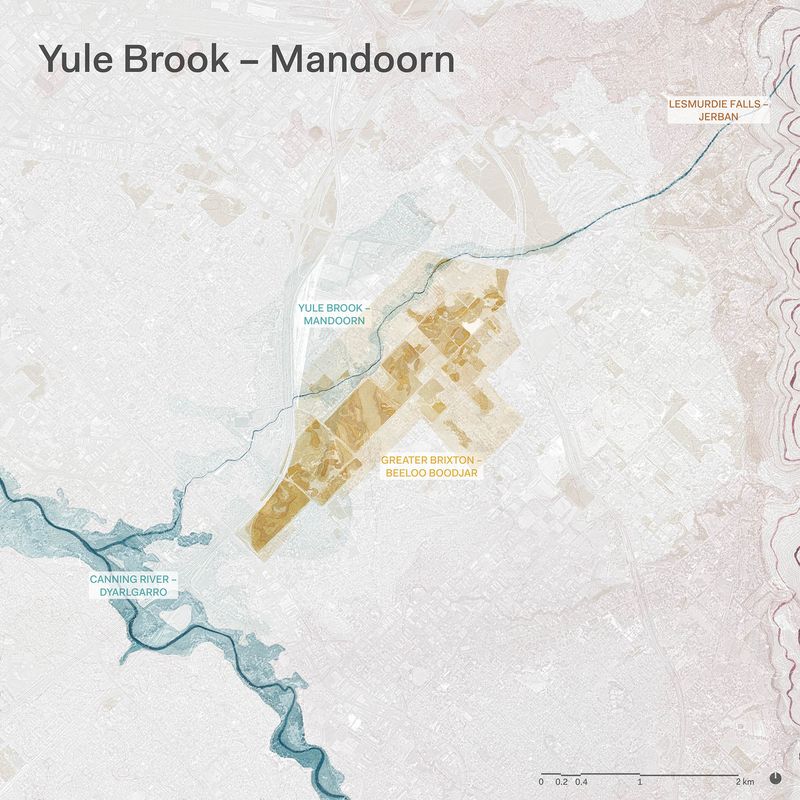

In the early 1990s, the University of Western Australia ran an interdisciplinary design studio called HOPE that synchronized design and landscape in a unique way that, for me, seemed to demonstrate a tangibly West Australian language for landscape tied to the transition between sand, low plants and big sky. Recognizing that this landscape is a modified one and that its unique qualities can be brought out through representation, Daniel Jan Martin’s gorgeous design research thesis (with Monash University) seemed a tangible link between the UWA of old and the landscape architectural thinking of now. Martin presented a series of maps depicting an aquifer near Perth and the landscapes above it, showing both surface and subsurface and revealing potential landscape management strategies. The domains of landscape ecology and design can seem to be very different ways of seeing – the innovation of Martin’s project lies in how it extends the objectivity of the map to become speculative, as well as in its acceptance of novel ecosystems and weed-scapes.

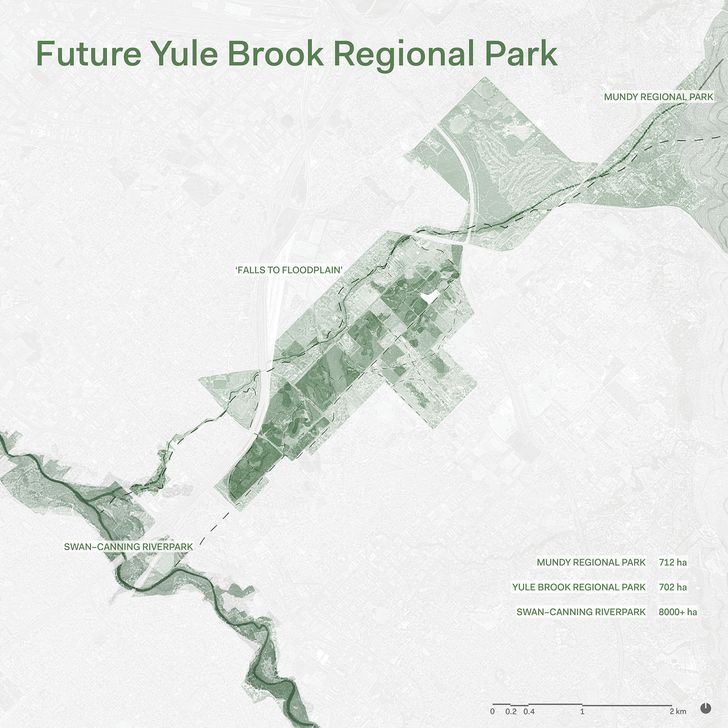

Beneath Noongar Boodjar are deep waters, surfacing as tapestries of wetlands and streams throughout the Perth landscape. These deep waters form aquifers with intricate fluctuations and flows, sustaining much of the phenomenal biodiversity on the surface of Perth.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin

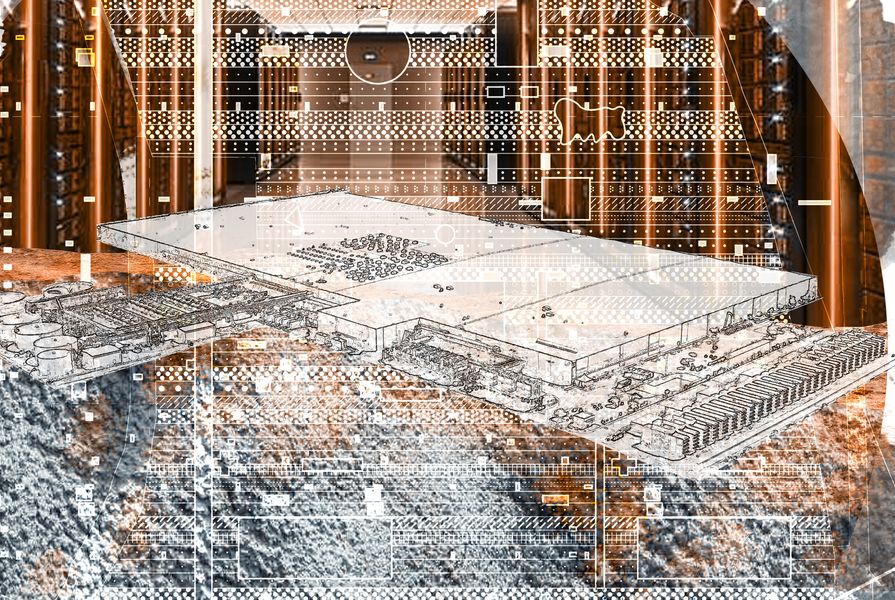

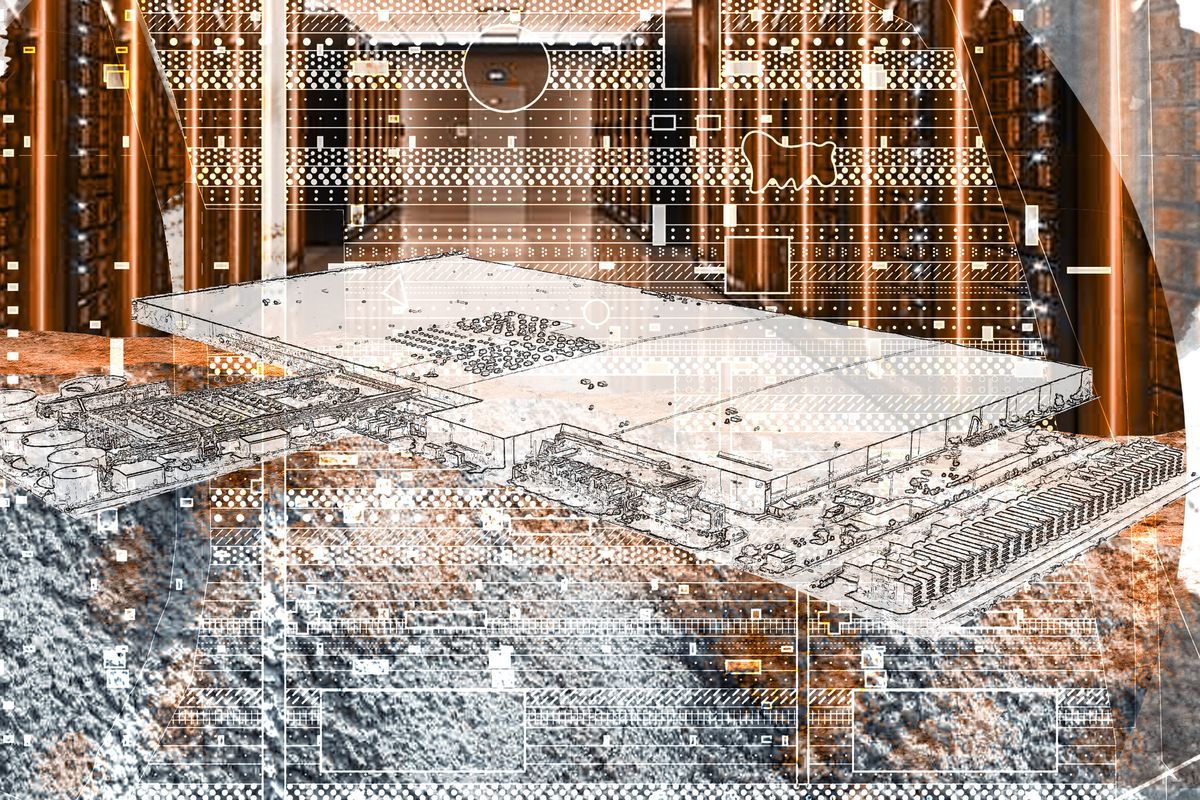

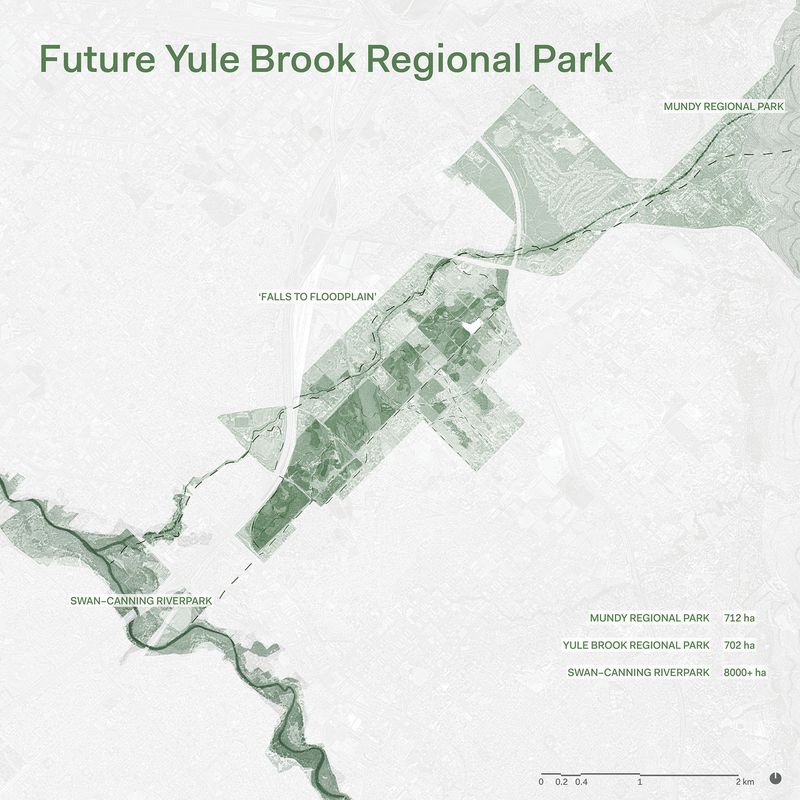

Yule Brook is an important corridor for the future of Perth, with some of the highest rates of biodiversity in the world, and negotiations to create a regional park are ongoing.

Image: Daniel Jan Martin

Among the turbulence of the “Spectacle and Collapse” presentations, there was real import to Margaret Grose’s observation that we can choose to see the future of climate change that we discuss with landscape architecture students not as one of doom and gloom, but as one of adaptation and potential renaissance. Need collapse come after spectacle? The positioning of “Collapse” after “Spectacle” in the conference’s title may at first have seemed like a negative culmination, but the emphasis on plants and ecology in the program’s discussions should remind us that our environment is not static, that the concept of “climax communities” in ecology is no longer. The seemingly stable places and times we inhabit, and those beyond, may be only moments before the next disturbance, or “collapse.” After collapse comes new growth and the emergence of a new “spectacle.”

1. I argued this in my 2018 book, Overgrown: Practices between landscape architecture and architecture.