Not all parks get built in a year. The Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton is still in its infancy after twenty. It’s slow growth, but growth well-fuelled by community power, the project’s nature as a botanic garden, strategic moves over many years, and some right-place-right-time luck.

In Yorta Yorta country and on the Goulburn River, Shepparton has a population of 60,000 and is a regional capital and irrigated food bowl. The story of its botanic gardens begins back when Jeff Kennett was premier of Victoria (1992–1999). Greater Shepparton City Council was selling a large landscaped block as part of the state’s asset divestment drive. Opposing the sale, locals proposed a botanic garden. The eventual sale of the land strengthened this botanic gardens advocacy group and one member, Jenny Houlihan, ran for council, was elected in 2005, became mayor two weeks later and for six years argued for the creation of a botanic garden. When she finally got the numbers on the council, the CEO took her out to Shepparton Tip.

Shepparton Tip had been a towering and obscene pile of God knows what, dressed occasionally with excavated soil, rising higher and higher over a period of fifteen years until the Environment Protection Authority finally shut it down. By the time of Houlihan’s first visit, the council had completed the remediation of the site and the mound had been capped. But cut-up by mountain bikers, hit with ongoing dumping, and located on a floodplain mudscape, the site was far from pretty. What it did constitute, though, was 22.6 hectares on the Goulburn River, located just near the waterway’s confluence with the Broken River and right on Shepparton’s southern edge. There were eight hectares of remnant bush, and it was the only council land available of sufficient size.

A series of steeply terraced gardens leads up to Honeysuckle Rise lookout at the top of the mound.

Image: Kirsten Bauer

The Refugee Garden celebrates Shepparton’s rich multicultural history with its collection of native cultivars and hybrids.

Image: Kirsten Bauer

Early site works

The early works capping the mound had been undertaken by Coombes Property Group in the years before its use as a botanic garden was decided. The landscape architect for these works, Rob Cooper, had previously been involved in a successful landfill restoration project, All Nations Park in Melbourne’s north. At the time, the only viewpoint in Shepparton was the local communications tower, and Cooper understood well the potential of the mound’s elevated ground. His ability to talk landfill got Greater Shepparton City Council engineer Roger Smith to understand the opportunity for creating a green space that would offer views over the surrounding trees.

Working with Smith, Cooper raised the mound’s capped height. Works included creating ramps along the mound’s sides to allow easier access to the top and re-grading the site’s too-steep slopes – some terracing, he concluded, would make future plantings easier. Peter May from Burnley College (now The University of Melbourne) advised Cooper on using mature biosolids for soil improvement and on directly seeding the mound with native grasses. The scarred area of the “borrow-pits,” where soil to dress the rubbish mound had been excavated, was remodelled as a floodway with stabilized edges. These early works were done with little extra cost to the council, beyond what had to be spent anyway, and they have given the site great bones.

A working bee run by Friends of the Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton in 2017.

Image: courtesy Friends of the Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton

Broken footpaths and kerbs from around Shepparton have been made into platforms and steps for the gardens.

Image: Kirsten Bauer

Developing a masterplan for a botanic garden

In 2011, Greater Shepparton City Council set up a community committee to manage the site, and a masterplan for the Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton (ABGS) was commissioned – but money was on drip feed. Rob Cooper from Spiire was again involved, but he moved on in 2013, with colleagues Alexandra (Alex) Lee and Tim Mitchell taking on a (paid) labour of love. Workshops followed and approaches to design outcomes emerged: dry climate gardens; regenerating remnant bushland; four local vegetation classes; recycling and sustainability; Shepparton’s irrigation landscape; Yorta Yorta country; the successive waves of migration and refugees that have made Shepparton richly multicultural.

Mitchell was full of ideas from studying a Master of Horticulture degree at Burnley College, and he dived into plant research. Lee was a young RMIT graduate. The first plantings for the site went in before the completion of any masterplan, at the highest point of the mound. Designed to be viewed from above, these plantings represent the Shepparton food bowl, its dry land and irrigated grid broken by rivers. Native food species include Kunzea, pigface, Themeda and saltbush. Because of the capping, no trees were planted.

A masterplan followed, focused on the mound, now renamed Honeysuckle Rise after a rare banksia of the now-lost sandhills of the region. For those visiting the gardens today, Shepparton’s long history of migration is captured through a garden of hybrids and cultivars, and an avenue of wattles lies along the mound’s edge. There’s a Myoporum lawn. An Indigenous land-use garden has also been proposed.

One of the great strengths of the gardens is the use of recycled materials. Jenny Houlihan deluged the Spiire’s design team with photos from the council depot. Broken footpaths and kerbs have been assembled into platforms and steps. Carefully graded bricks have been built up into benches, like liquorice all-sorts. Old Dethridge wheels, an Australian invention vital for irrigation, were repurposed into planters carrying the honeysuckle and the Pittosporum angustifolium of the sand hills. Local artist Tank worked up one wheel into a giant sunflower; concrete culverts have been turned into more planters, adding height.

The recycled wonderland continues with local landscape designer Louise Costa of Design by Nature’s work on the Children’s Garden located in the north-eastern part of the site. The marvels in the Children’s Garden include a fabulous and comforting shelter made of bed springs and a tree crafted from exhaust pipes. The adjacent Weaving Garden, also by Costa, has its origins in workshops with weavers from local Indigenous organisation Kaiela Arts, and the planters that Costa’s husband, Les Pelle, fabricated for the project bear representations of plants traditionally used by the Yorta Yorta people for weaving.

The overall site has grown incrementally over time and space, with careful advice, small steps and considered moves bringing threads and themes together.

The planters fabricated for the Weaving Garden bear representations of plants the Yorta Yorta people traditionally use for weaving.

Image: Kirsten Bauer

One of several sculptures created by members of Splinter Contemporary Artists and installed along The River Walk at the gardens.

Image: Tim Mitchell

Expanding connections

Regional Victoria has a wealth of botanic gardens, many designed by William Guilfoyle. Shepparton’s stands out as contemporary for its focus on showing native Australian species. In 2011, the garden’s community committee members went on a mission to research progressive approaches to botanic garden design. The design of ABGS takes inspiration from planting design, a strict approach to water use, and the push for Australian plants in domestic yards demonstrated in TCL’s design for the Royal Botanic Gardens Cranbourne (RBGC).

Early discussions by community committee members with the staff at RBGC identified two areas for specific collections. Remarkably, the ABGS is the first botanic garden in Australia to focus on Acacias. Its other specific collection centres on the Thomasias, a genus of small shrubs with papery sepals endemic to the south-west of Western Australia.

Since then, the gardens’ engagement with Cranbourne and other botanic gardens across Australia and New Zealand has grown. In 2019, the ABGS joined RBGC’s Care for the Rare program, where threatened species are propagated for ongoing custodianship by program members. In this latest step in strengthening the identity of the project, local landscape architect and RMIT alumna Melissa Stagg of Stagg Design has been collecting seed for propagation around the region, working with RBGC staff to identify suitable species and incorporate them into the indigenous planting beds she has designed at the ABGS.

A community-driven project

The success of the ABGS today owes much to the dedication and drive of local Shepparton community members over the past two decades. The plantings on Honeysuckle Rise have been propagated, planted and established by the Friends of the Australian Arid Lands Botanic Garden group, who continue to water them by hand – there is no electricity, nor town water on site. The Weed Warriors, a local weeding group, have brought the remnant bushland back – orchids poke their heads up now. Grant applications have been written and funding found. Local birders now conduct two-month surveys across the site, providing additional support for grants, adding to knowledge about the garden and its biodiversity and expanding engagement. The floodway remodelled from the borrow-pits has now become a series of attractive wetlands, filled half the year from the backwash flooding where the Goulbourn River and Broken River meet. The site has been surveyed for flora, there are evening events for spotting gliders, and various schools and bush kinder visit. Shepparton Festival holds a film night on Honeysuckle Rise, and the site hosts art and weaving classes, as well as joggers and cyclists passing through. The pandemic has brought more people seeking the respite of cared-for public open space. Except for major infrastructural works, all the work on the garden has been undertaken by volunteers and Work-For-The-Dole teams. Plants come from a local nursery run by and for people with disabilities. The community-led initiative RiverConnect aims to return the Goulburn and Broken Rivers to their rightful stature across a region where their function as a resource for irrigation is overwhelming.

Alex Lee, contemplating the ABGS as Spiire’s longest running project, says at first she was disappointed and frustrated with the lack of funding. But she knows now over time that this has made this project richer. It has given more people the opportunity to engage and feel ownership and investment.

The Food Garden features native species like Kunzea, Themeda, pigface and saltbush.

Image: Tim Mitchell

The future of the gardens

Three years ago, Greater Shepparton Council took over management of the gardens. This has been a difficult time for the volunteers, but it also means that better infrastructure is now coming to the site. Town water and solar-powered irrigation are in the works, and a bridge over the Broken River and a shared path have finally created improved connections between the gardens, Shepparton’s Victoria Lake precinct, and the area’s new drawcard – Shepparton Art Museum. Visitation to the region is skyrocketing.

Now, the council is considering the site’s wetland areas, as well as possibilities for developing a seed nursery, an orchard of indigenous species, and opportunities for Indigenous-led education on site. Damian Doller, the council’s team leader of Landscaping and Native Open Spaces, describes the gardens as the “jewel in the crown [of the area].”

The gardens’ evolution demonstrates a number of landscape design principles. Through a project like this, a committed community can transform a place from the inside out. Responding to place and consistently applying thoughtful ideas makes for a strong design. A big budget is not essential, though good infrastructure never goes astray. Masterplans can unfold over decades. Good topographic decisions at the beginning can create great form for future work. Well-designed botanic gardens can be the key to a broader network of green spaces.

Not a bad outcome for the old tip.

The Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton is located on the land of the Yorta Yorta people.

Source

Review

Published online: 30 Sep 2022

Words:

Adrian Marshall

Images:

Kirsten Bauer,

Tim Mitchell,

courtesy Friends of the Australian Botanic Gardens Shepparton

Issue

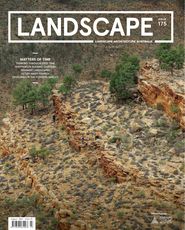

Landscape Architecture Australia, August 2022