When exploring queering public space, notions of safety, access and equity are ubiquitous. LGBTIQ+ communities have been – and continue to be – subjected to ongoing persecution and violence, particularly in the public sphere. Restrictive heteronormative dichotomies play out in all aspects of life, including the way our cities are designed and governed. It makes sense that safety is an integral objective of any queering of landscape architecture practice.

But what other possibilities are created by queering landscape architecture? And what opportunities might be generated by dismantling the binaries in landscape architecture practice? Can queering landscape architecture make landscape architecture – as a profession, a discipline, a methodology and a built outcome – more democratic, more equitable, more sustainable, more playful and more beautiful?

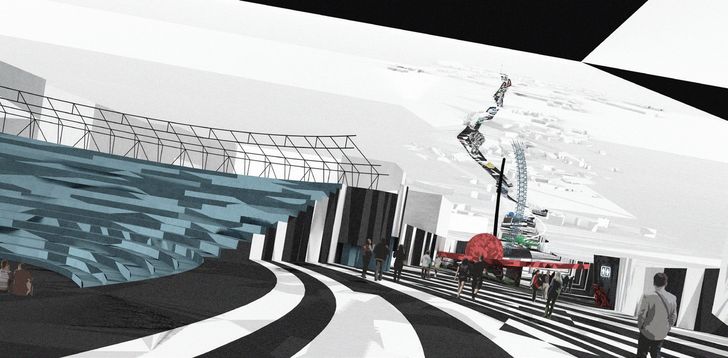

A digital collage by Felipe Coral of Roberto Burle Marx’s Jardins do Museu de Arte Moderna, a public landscape where the politics of Brazilian modernism have clashed with the realities of queer urban life in Rio de Janiero.

Image: Felipe Coral

Queer Ecologies was a long table discussion held on a Saturday afternoon that explored the generative potential of queering in and around the discipline of landscape architecture. Organized by AILA Victoria’s Cultivate committee as part of Melbourne Design Week 2021, the session was diverse and creative, demonstrating that the potential for queerness in landscape architecture is infinite. The session, which unfolded over a three-hour themed lunch, included six speakers from diverse backgrounds working across design, architecture and the arts.

Set in a sun-dappled courtyard of Volker Haug Studio in Brunswick, guests and speakers gathered and greeted each other, perhaps like old friends. Very fitting, considering community is integral to queerness.

The event’s first presenter, Pip Wallis (Curator, Contemporary Art, NGV), spoke of how gardening and landscape were intrinsic to Edna Walling’s creation of a supportive and diverse community. Through acts of gardening and landscape design, Walling and her community endeavors could do away with normative ideas of the feminine and masculine. Walling’s photographs of places where she built community, such as Bickleigh Vale, Mooroolbark, will be included in a forthcoming exhibition at the NGV titled Queer, currently under development.

From left to right: Alistair Kirkpatrick (Co-director, AKAS), Pip Wallis (Curator, Contemporary Art, NGV) and Sarah Hicks (Co-director, Bush Projects).

Image: Emily Wong

A paperbark-baked dish of barramundi prepared by Fluff Corp (Claire Lehmann and Jia Jian Chen).

Image: Emily Wong

We then moved inside to take our seats at a table draped in lotus and bamboo leaves and featuring parcels wrapped in melaleuca leaves. Food designers Fluff Corp, who are also ceramicists, presented a pescatarian meal adapted from traditional Indigenous and Chinese recipes and cooking techniques, to be consumed without ceramics. The dishes, ranging from paperbark-baked barramundi to clay-fired pumpkin, offered a delicious deconstruction of binaries in biology, art and cooking and an invitation to interact and connect in new ways.

RMIT lecturer Brent Greene and AKAS co-director Alistair Kilpatrick positioned their hypotheses for queer plant communities within a chronology of ecology, a term first coined in 1866. Is the normative construct that exotic plant species are bad and native plant species are good undermining possibilities for more sustainable futures? We are now becoming more aware of precolonial indigenous landscape management practices. But how do we apply these learnings in highly modified urban landscapes? Perhaps in these environments, exotic plant species have untapped landscape restorative value.

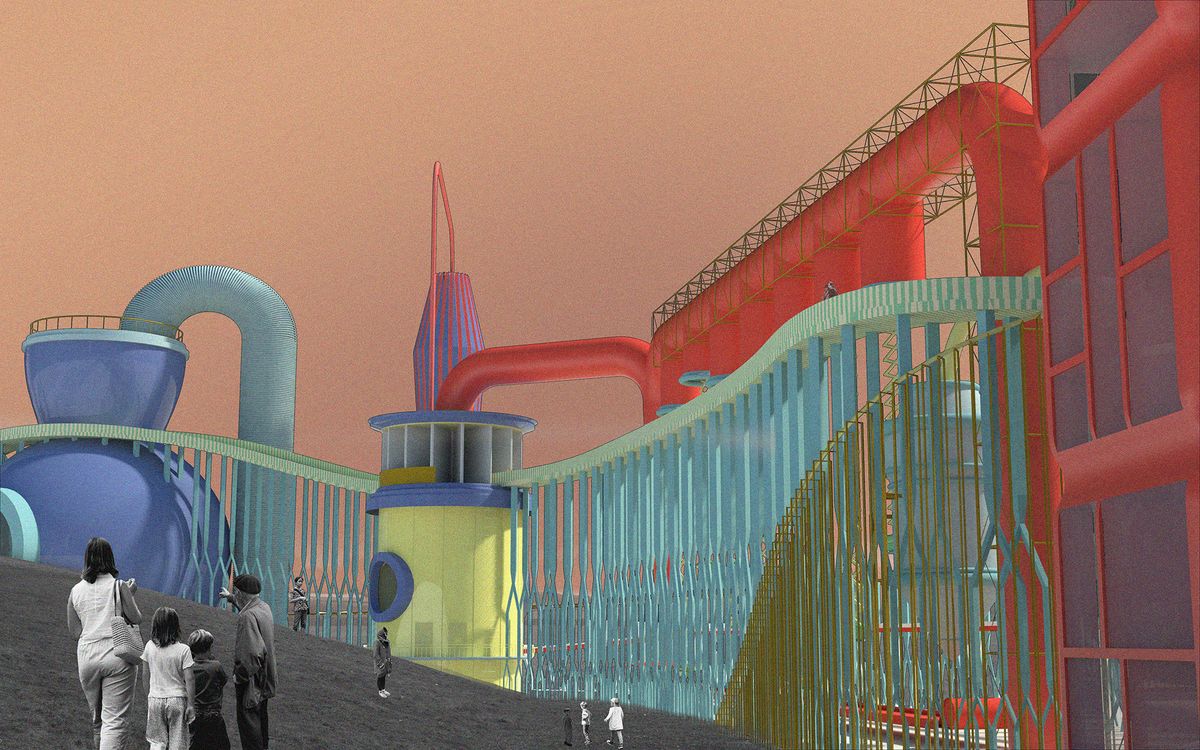

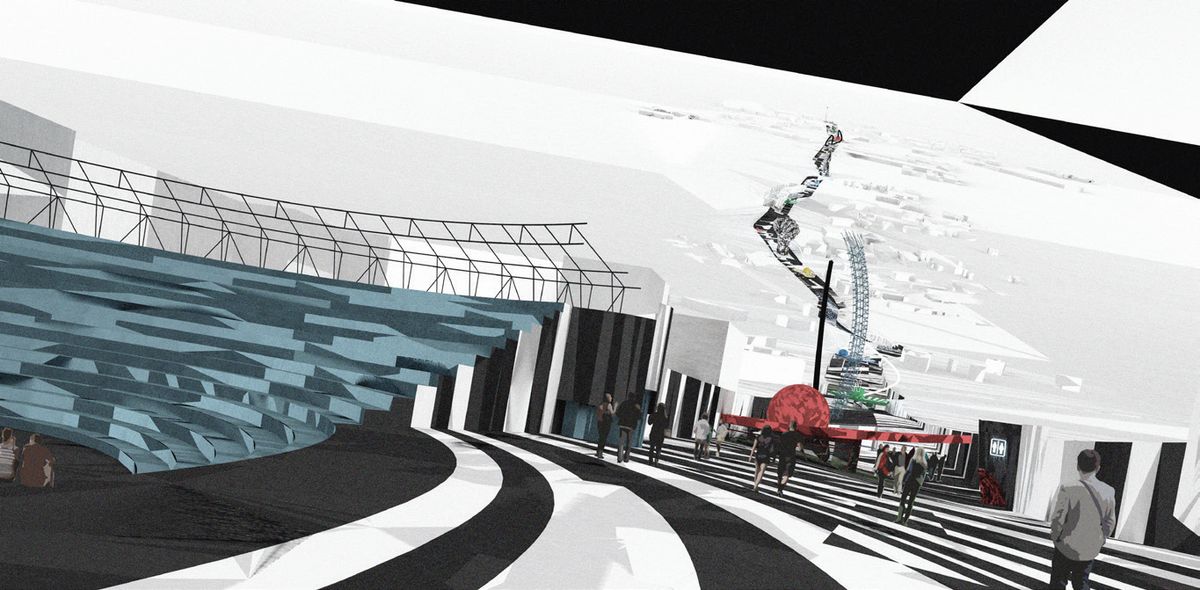

Darius Le’s research considers the failed Melbourne Olympic bids as an opportunity for developing future design speculations for the city.

Image: Darius Le

Public space has long been where queer communities have met and connected. But it is also in public space that heteronormative structures are heightened. Public space can provide for expressions of identity, diversity and community. Read any gender theory or article on the policing of toilets. It is in these places such as these that the gender binary and normative concepts of masculinity and femininity are often most violently reinforced. When considering queerness in landscape architecture, we need to understand ideas of inclusivity and access. The design and management of spaces nurtures certain activities and users over others.

Over a three-hour lunch, guests and speakers from diverse backgrounds across landscape architecture, architecture and the arts discussed the possibilities for queering landscape architecture practice.

Image: Emily Wong

As a landscape architect and a proud queer woman, I know how queer events (Mardi Gras, Pride, Carnival Day, for instance) can not only give visibility to often less visible communities, but also transform public spaces into colourful, diverse, beautiful and exciting places to be. In the final talk of the afternoon, architect and researcher Darius Le suggested that to always focus on safety and danger in the search for queer design might limit the possibility for queerness to be creative, beautiful and playful. She got us thinking that queering landscape architecture might be flamboyant, eccentric and fun – an urban spectacle. Famous landscapes are not exempt from management policies that are biased. The unplanned occupation of Roberto Burle Marx’s Aterro do Flamengo (Flamengo Park) in Rio de Janeiro, has resulted in the marginalization of indigenous peoples and the eviction of the city’s queer communities. “Queering landscape architecture can help us create management policies that will democratize public space,” argued Felipe Coral, landscape architect at Bush Projects and another of the event’s guest speakers. Coral’s research challenged the homophobic and racist policies that govern public space and manifested in a proposal, titled “Informal Gardens,” that deployed landscape architecture strategies to reconcile queer informal public activity and urban ecologies.

Darius Le’s research investigates how urban spectacle might be used to reconfigure relations between infrastructure, heritage values and representation.

Image: Darius Le

Queer Ecologies was exceptionally thought-provoking and proved itself a queerer space. While we may not have an easy answer to what queering landscape architecture might entail, we must ideate and question the structures that underpin decisions about our built environment. Landscape architects must engage with diverse communities, and this must include LGBTIQ+ communities. But we also need to know when to create the space for other voices to be heard.

Queer Ecologies took place at Volker Haug Studio on Saturday 27 March as part of the Melbourne Design Week 2021 program.