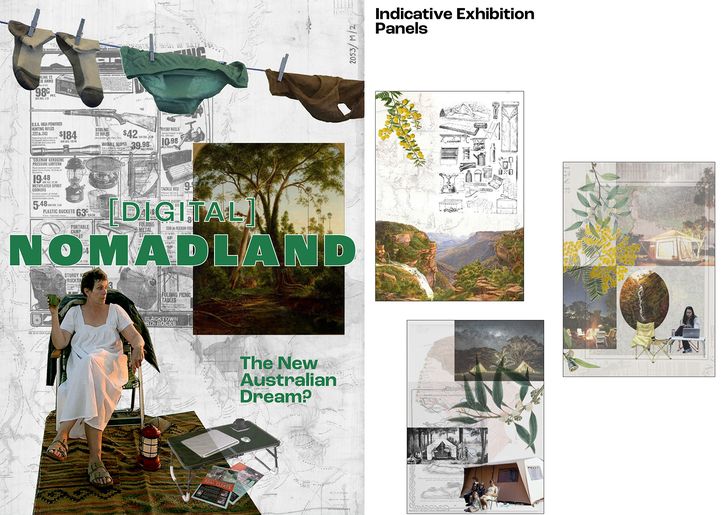

A proposal for an alternative living model that engages the popularity of the “digital nomad” movement and combines it with environmental restoration has been announced the winner of a window design competition run by RMIT University’s landscape architecture department and RMIT student landscape architecture body, SLAB. The competition challenged entrants to rethink the meaning of “The Australian Dream” with the aim of opening up dialogue around the shifting nature of the Australian landscape and its cultural narratives.

The winning proposal, [Digital] Nomadland: The New Australian Dream?, was developed by Ricky Ricardo, Carl Hong and Jobelle Villaneuva, designers at the Melbourne studio of GroupGSA. It has been installed in the window display space of RMIT Design Archives in Carlton as part of the university’s 2022 end-of-year landscape architecture exhibition, themed “Liminal Practices.”

Digital Nomadland rejects notions of land ownership and permanent dwellings to explore nomadic ways of living.

Image: Ricky Ricardo

“[Digital Nomadland] rejects the fundamental idea behind the Australian dream – land ownership and permanent dwellings – to explore an alternative that is more aligned to the way humankind lived for most of our existence as a species: nomadically,” the winning submission reads.

“A subscription-based model [allows] members [to] access a network of camps around the country for long-term living and environmental restoration. Members need to have their own vehicle and basic camp equipment and can stay in any one location for up to 30 days. The camps offer amenities such as toilets, bathrooms, fresh water, solar power and communal workshops and kitchen areas, as well as social spaces and events. The camps … offer super-fast satellite wi-fi and remote working infrastructure, and members are required to participate in environmental restoration projects in the area for a minimum of 10 hours per week.”

“The subscription allows for an exciting lifestyle that is healthy for both mind and body, communal and meaningful … [one can live a] life that is closely connected to nature, yet still access the modern amenities that [we] can’t live without.”

Landscape Australia spoke to the team about the contemporary issues that drove their design concept and exhibition-making as spatial practice.

Emily Wong: What are the issues you wanted to tackle in your proposal?

Ricky Ricardo: The vision is a response to the theme of the competition brief, which invited us to critique the idea of The Australian Dream. Our response assumed the death of The Australian Dream as this egalitarian idea that if you work hard enough, then anyone can afford a piece of land and a house close to where they work. This ideal arguably ended around the year 2000 when property prices skyrocketed compared to incomes.

Digital Nomadland was inspired by a number of things, one of which was a chapter in the book Sapiens called “History’s Biggest Hoax,” which suggests there was a decline of quality of life that occurred 10,000 years ago when homo sapiens began to live permanently in one place during the agricultural revolution. It’s also inspired by trends that came out of COVID-19, such as the idea of the digital nomad, that were a reaction to having to work from home, to being stuck in one place. We see this trend with things like the new digital nomad visas some countries are offering and the growing van life movement.

The Digital Nomadland competition entry – the proposal questions the way humans currently inhabit the planet and provokes consideration of radical alternatives.

Image: Ricky Ricardo, Carl Hong and Jobelle Villaneuva

Could you talk about the process of creating the exhibition?

RR: There are a few parts to the exhibition – the hanging banners which are collage-based and speak to landscape and memories of camping and being outdoors. And then there are personal objects, which aim to show signs of life. The television is a bit nostalgic.

Jobelle Villaneuva: We had the printed banners and decals professionally printed and installed by Boom Studios, and we curated and installed the rest ourselves – with the help of the RMIT Design Archives.

What challenges did the installation present? Did you need to make adjustments to the proposal during the installation process?

RR: We did have to redesign it a little [during the installation] but we’re happy with the outcome in the end. We originally wanted to mimic a sense of the ground in the space, but the rules of the gallery restricted us from using gravel, sand or plants in the space. So our approach was to work with the clean “gallery” nature of the space and introduce specific elements that could sufficiently tell the story.

Carl Hong: We didn’t want it to look like a display for camping equipment, instead we wanted to express the beauty of the Australian landscape through a combination of digital media, objects, and paintings. There were many constraints that had to be considered, including budget and the exhibition space. The work had to present well day and night and in different weather conditions.

The winning proposal for the Digital Nomadland installation was inspired by trends arising out of COVID-19, including the idea of the digital nomad.

Image: Ricky Ricardo, Carl Hong and Jobelle Villaneuva

How do you hope people perceive the work?

JB: We wanted the installation to relate to different types of people, including the older generation that would have had this Australian Dream of owning a home, but also to different audiences as well. We wanted passers-by to walk past, look and be attracted to [the display], so we had to think about different ways to engage people that might passing through the area. We were very selective with the objects we chose to include, together they needed to quickly evoke a memory.

RR: The exhibition offers such a drastic counterpoint to the context of the RMIT Design Archives and the RMIT Design Hub [on Swanston Street] surrounds which are – for Melbourne, in particular, quite harsh – there are no trees, it’s all hardscape, and surrounded by the road and nearby office and student residential towers.

We have sound coming through the window of a one-hour loop of Australian nature, mostly birdsong. The video footage of the landscape moves slowly, offering something a bit like a virtual forest-bathing experience. We hope the sound of the magpies really transports visitors to a different place.

We’re really interested in how we can inhabit the landscape in longer-term ways that are less detrimental and destructive and more restorative. It’s very hard to live without having a fixed address in Australia – you can’t even park a car overnight [without a permit] throughout most of the country.

Do you see any potentials for landscape practice in this proposal?

CH: Reflecting on the competition and our profession as landscape architects, [the competition entry] was a chance to rethink our roles as designers and how we operate differently to other spatial design professions.

RR: Digital Nomadland is ultimately an artwork. It’s not a proposal for a utopia – the exhibition isn’t saying, “well, everything would be fixed, if we were to do this.” Instead, we wanted to put out a radical alternative to the status quo that generates discussion, to start to get people to rethink the way that we live and inhabit the world.

Digital Nomadland is on display in the RMIT Design Archives at 154 Victoria Street, Carlton from 14 November to 27 February 2023.