Kerb issue 28, titled Decentre: Designing for coexistence in a time of crisis addresses the seismic disturbances of 2020, a year of catastrophic bushfires, an ongoing global pandemic and increasing awareness of systematic inequalities across race, gender and class. This is all underpinned by the even more dramatic awareness of the climate emergency our world is facing. As the issue’s editors note, where landscape architecture is engaged with these occasions, it ought to consider what its responsibility to tackle these should be. Bringing together contributions from far and wide, Kerb 28 destabilizes a mainstream “centrist” worldview to point us in a new direction.

The issue is organized through the topics of “Framing,” “Mapping” and “Shifting.” Articles under “Framing” describe how dominant structures of power reinforce social inequality, exploitation and nature’s extraction. Stephen Muecke, a professor of creative writing, describes the limitations of translating physical experiences of Country through digital means, warning that in doing so we may miss out on mind-shifting experiences of alternate realities. Further to this, we need to be critical of who really benefits from such work – “possibly a coder in Santa Monica” – instead of First Nations people on Country. This critique could be extended beyond Muecke’s essay to digital translations of designed landscape and instances of cultural appropriation in placemaking.1 In his contribution to the issue, designer and urbanist Dan Hill builds on his Slowdown Papers of 2020 (a series of reflections on the impact of the COVID–19 pandemic on city systems, infrastructures and technologies) to unfold the perils of infinite growth on a finite planet. Popular contemporary philosopher Timothy Morton seduces us with affirmative statements about landscape architecture’s value over “objectified” architecture that ignores the “lifeforms that inhabit and surround it.” Morton’s argument is intriguing in its extension of agency to non-human objects. Still, it has been criticized, along with broader “object-oriented” philosophy, for its obscuring of existing inequalities and hierarchies of power, effectively de-politicizing design conversations.2

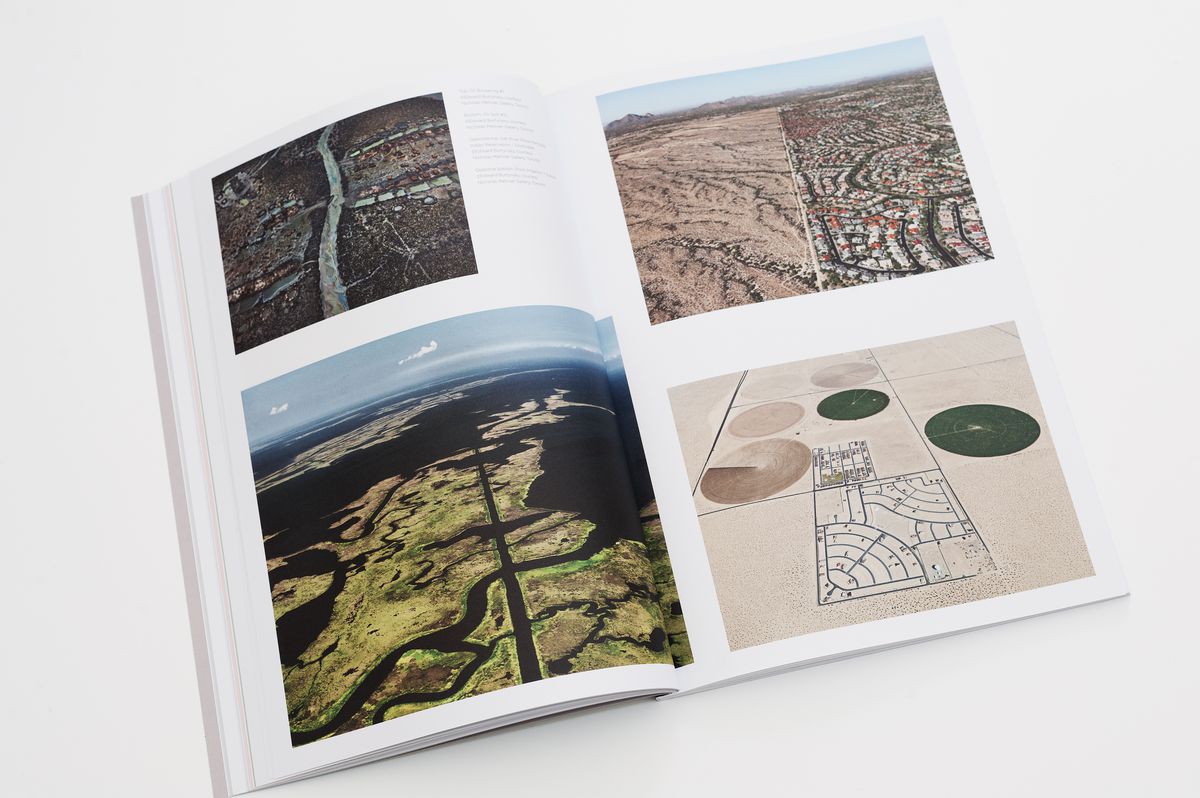

A spread from the pages of Kerb 28, which includes contributions by Edward Burtynsky, Dan Hill, Etienne Turpin, Hannah Hopewell and Anna Tsing.

As we move through the issue’s “Mapping” chapter, contributions from authors crossing art, performance and landscape architecture describe projects that destabilize their audience. Danish choreographer Mette Ingvartsen, for example, describes her Artificial Nature Project, a performance where non-human “actors” of foam bubbles, particles and vibrations are given licence to affect their spectators. Similarly, Australian Janet Lawrence’s art promotes an ethics of care across species through the installation of a “medicine garden” – not for people, but for plants. Writing from within the landscape architecture discipline, Penelope Allan and James Melsom recount the nation’s recent bushfires, where fire and ecology are interwoven with conflicting agendas and inflexible management approaches. Accompanied by sophisticated high-resolution point cloud maps, the article highlights how much we urgently need more research in this field, and how landscape architecture’s generalist skill set might contribute.

And then to “Shifting.” In the issue’s final section, we are presented with practices that reach for desired points beyond the centre – that “decentre.” Greg Grebasch, a dedicated ally of First Nations peoples in Australia, converses with Noongar artist Barbara Bynder about their cultural mapping project – a map, evocative painting and live document – that will guide future development on Noongar Country, the site of Perth. Crossing to the United States, we discover the field experiments of landscape maintenance enthusiast Michael Geffel, who encourages us to get our hands dirty in the garden. Geffel’s work focuses us inward to landscape fundamentals, but I’m left wondering how landscape practitioners might extend this approach outward to better engage the problems he suggests are “out of our control.” Hannah Hopewell, a landscape architect and lecturer at Te Herenga Waka – Victoria University of Wellington, bookends the issue with a thought experiment: Where might we go if we discarded traditional concepts of landscape that have been framed through image-making and are rooted in colonialization and market forces?

Together, these contributions encourage a more heightened awareness of humanity’s impact on earth systems – impacts that have taken on a scale perhaps never before imagined. Reconsidering our relationship with the natural world has never been more pressing. While some in the world argue for climate geoengineering to maintain business-as-usual, others advocate for adapting to these conditions, which are of our own making. This latter attitude aligns with many of the contributions in Kerb 28, with references to Bruno Latour and the idea that nature and society are so interwoven that distinguishing between them is no longer necessary or useful. This group would argue that we should give agency to non-human objects and allow them to have their say, while we adapt to conditions as they are. But, in order to reverse conditions of crisis, we need to understand their causes and their relationship with industrial capitalism, which is exploitative of and not reciprocal with nature. This would mean less fetishization of society-nature intermingling and more focus on building an awareness of the highly differentiated agency and power that humans currently possess, in contrast to the natural world. To describe this in other words, “nature cannot walk into a courtroom, but its human allies can.”3 Perhaps a future issue of Kerb might reflect on this and the entangled political, legal and strategic implications of landscape. We could, for example, start to imagine how landscape architecture work might align with policies that can create direct impacts – for instance, through advocacy for and visualization of a Green New Deal. Alongside this, it remains essential to think about the impact we can have as individuals, through the decisions we make, the projects we undertake, the materials we use, and the careful consideration of the people and environments we are designing for.

Kerb #28: Decentre – Designing for coexistence in a time of crisis. Edited by Alexander Maxwell-Anderson, Darcy Rankin, Yishi Wang, Beidi Ran, Hongxin Huang and Kate Trenerry, Uro Publications, 2020.

1. For a critical account of Indigenous placemaking, see Janet McGaw and Anoma Pieris, Assembling the Centre: Architecture for Indigenous Cultures, Australia and Beyond, (Abingdon, England: Routledge, 2016).

2. For an extensive critique of object-oriented philosophy, see Douglas Spencer, “Going to Ground: The Problem of Bruno Latour” in Clara Olóriz (ed.), Landscape as Territory: A Cartographic Design Project (New York: Actar Publishers, 2019) and Andreas Malm, The Progress of This Storm (New York: Verso, 2018).

3. Thea Riofrancos, “Field notes from extractive frontiers,” 28 September 2020, Centre for Humans and Nature, humansandnature.org/field-notes-from-extractive-frontiers (accessed 9 February 2021).

Source

Review

Published online: 1 May 2021

Words:

Liam Mouritz

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2021